New Delhi: The Cholas were pioneers of temple politics, dominated the Indian Ocean, made Tamil a global language of power and diplomacy, and shaped some of the most important developments in Hinduism. But their story remains largely absent from India’s historical imagination, overshadowed by myths and Delhi-centric accounts.

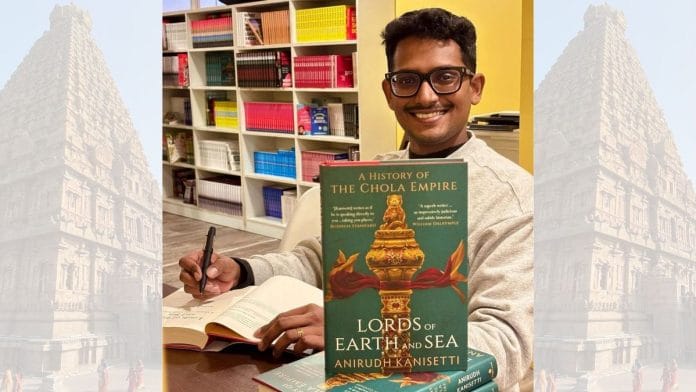

Public historian Anirudh Kanisetti’s new book, Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire, seeks to bring balance to the country’s civilisational understanding.

“You cannot really talk about India without talking about the Cholas. You can’t talk about the world without talking about them,” Kanisetti said in an interview to ThePrint.

In his book, Kanisetti challenges popular notions, including the idea of a Chola navy, cemented by Amar Chitra Katha comics and movies like Ponniyin Selvan. Instead, he argues there was a partnership between rulers and merchants that drove their overseas expansion.

“Maybe the Cholas didn’t have a navy, but the Tamil merchants did,” he said, pointing to their trade networks stretching into Sumatra and Thailand.

And after centuries of dominance, what brought it all crashing down wasn’t an invasion but tax evasion.

Here are edited excerpts from the conversation. For the full interview, visit ThePrint’s YouTube channel.

Also Read: How Rajaraja Chola became the world’s richest king

RL: Your first book, Lords of the Deccan, was a finger-wagging admonishment. You told us that we do not know enough about southern history. Your second book, Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire, takes that argument forward. It goes right into the beating heart of Tamil history—the Chola Empire, a rule that was profoundly ambitious and audacious in its imagination and reach. But why is it that so many of us know so little about the Cholas?

AK: I think this applies to a lot of pre-modern Indian dynasties. In the 19th century, when the British were deciphering the Brahmi script, nobody remembered who Ashoka was. Generally speaking, the dynasties that are remembered historically depend a lot on the politics of the country that is seeking to remember them.

If you look at the history curricula developed in India post-independence, there is a very clear urge to create a sense of a unified national history by focusing primarily on the big Gangetic empires. You can imagine the curriculum writers sitting in Delhi, linking themselves to the monuments that they’re surrounded by.

The Cholas were extremely influential. Not just in terms of Indian history, but also in terms of the Indian Ocean and global history.

An unfortunate casualty of this has been South India, which has been essentially seen as a periphery. Yes, it had empires, but there isn’t a clear sense of the continuity of these empires into the present-day making of Indian society and civilisation. The Cholas are a fantastic example of this.

Yet, the Cholas were extremely influential. Not just in terms of Indian history, but also in terms of the Indian Ocean and global history. Some of the most important religious developments in human history, especially in Hinduism, came from the Tamil country. The integration of the Indian Ocean world came from the military raids the Cholas undertook.

So, you cannot really talk about India without talking about the Cholas. You can’t talk about the world without talking about them.

RL: Let’s get to their politics. The template was one of mixing temple construction and politics. And, in 2025, it sounds familiar to many of us. Are you trying to say through this book that we’ve been here before, and this isn’t unique or unprecedented?

AK: The idea that religion and politics can or should be separate is a very European one. It comes from the Enlightenment, when the church was losing its stranglehold on the production of knowledge. For a medieval Indian ruler like Rajaraja Chola, building a great temple wasn’t necessarily just a devotional act. You see this in the inscriptions, where it’s not just the king who’s making gifts, but also his army regiments and generals.

Now, why was it important for this army regiment to publicly declare this and have it carved onto a temple? It was a way of displaying their allegiance to the [king] and their devotion to the gods.

The Chola administrative structure was not just the royal family, but a wide cross-section of Tamil society. They were able to mobilise resources on a scale that had never been seen in India up to that point.

You have this interesting situation where the entire Chola court is participating in a project of building this temple as a way of bringing themselves closer to Shiva, but also as a way of publicly affirming their closeness before the world.

Because whoever came into the temple could read these inscriptions and see how the various organs of the state came together to worship the god.

RL: These are not just temples. They are temple complexes, like the Vatican, but centuries before it. You even compare the Cholas to the Medicis of Italy. The Tanjore (Brihadeeswara) temple is 40 times bigger than any other temple of its time. The imagination, the sheer scale, and the unprecedented speed at which these temples were being built—how were they managing to do it?

AK: I think the Cholas had one of the most extraordinary administrative setups of the medieval period. If you look at the inscriptions of most medieval Indian states, you will see that a king usually had a council of ministers—often aristocratic men intermarried with the royal family. But the Chola administrative structure was not just the royal family, but a wide cross-section of Tamil society. They were able to mobilise resources on a scale that had never been seen in India up to that point.

The Brihadeeswara Temple is a case in point.

If you look at cathedrals in Europe, they’re started by one set of people and continued over the centuries, whenever a city-state has the resources. But with Rajaraja Chola, you have an unprecedented situation. Through his conquests, he was arguably the wealthiest man on earth and able to move resources at a huge scale.

We’re talking about a structure made of 130,000 tons of granite, built over just seven years. It started in 1003 AD and was done by 1010. That means he was moving about 7,000 tons of granite every year while also fighting multiple pitched battles in every campaign season.

RL: And that’s a good segue into the role of women in the Chola dynasty. I love that you focus so much on the queens—Nangai, Kokilan, and most importantly, Sembiyan Mahadevi, who was a phenomenal strategist. She wielded power behind the throne while the men were at war. She was actually running the administrative and financial hubs.

AK: Sembiyan Mahadevi in Ponniyin Selvan is a minor and very devout side character. We don’t fully understand the extent to which it’s the women who are pioneering some ideas that the men later pick up.

Rajaraja and Sembiyan are a perfect example of this. Here’s this formidable figure, Rajaraja’s grand aunt, and he must have grown up seeing what she was doing. So, it makes perfect sense that once he gets the throne, he seeks to do what she did on a bigger scale.

What was Sembiyan actually doing? She’s such an interesting character because we are able to sketch out at least the broad outlines of her life. We know she was married at a fairly young age. In her earliest recorded gifts, around 915–920 CE, she’s giving sheep to provide ghee to various very, very small temples.

In the 10th century, the prominence of Chola queens has no parallel anywhere in the subcontinent.

But even then, the temples that she’s choosing are very intelligent— they’re in the frontier regions where her father-in-law is fighting wars. So, she’s very clearly trying to make these connections to local communities.

And very briefly, because her brother-in-law dies, her husband becomes king. But then her husband dies at a very young age and she disappears from the inscription record. We don’t see her for another 20 years. Then, when we see her again, she is the queen mother and she has resources.

And she uses them in the same way as before, saying, ‘Here’s my son, King Uttama. My son is doing all these things, but here I am in your village. I am devoted to your god, and I am rebuilding your temple in stone as a sign of my devotion to your gods.’

RL: And she’s saying this in the inscriptions?

AK: In some cases, yes. But in most cases, it seems to be heavily implied. What’s very interesting about Sembiyan is that while she was rebuilding a village temple, she would also include her personal god in it—a Nataraja sculpture.

But there’s also this implied political connection. When she builds a temple, she says, ‘Okay, I’ve made this gift. Now the local assembly of this village will administer the gift on my behalf.’ It’s such a great way for her to build political connections while also exhibiting her devotion.

RL: And you say in the book that she was achieving what the kings couldn’t through war. Let’s talk about Nataraja. For many of us, Nataraja is synonymous with Chola bronzes. You call it a visual cultural revolution. There were some 3,000 Nataraja bronze sculptures in circulation around that time. How did this form become so popular?

AK: The idea of a dancing Shiva is a fairly old one. In fact, some of the earliest and greatest works of Sanskrit poetry have descriptions of this dance. But the precise depiction changes a lot.

For example, there’s this famous dancing Shiva from Badami, the former capital of the early Western Chalukyas, where he’s got 18 arms, all held in different mudras. But the posture is completely different from the Nataraja that we are all familiar with.

It seems that the earliest ideas of how Shiva as Nataraja should look developed in northern Tamil Nadu, probably around the 7th century.

But once Sembiyan Mahadevi enters the scene—and because she’s got a workshop of sculptors collected from all over the Tamil coast—she uses them in practically all the temples and bronze sculptures she commissions. By this point, these guys have a standard iconography, like how his leg should be positioned.

And because Sembiyan is constantly traveling to various small temples and commissioning a similar image of Nataraja, other people are picking up this beautiful image. That’s the visual revolution. It’s the development of this standardised iconography of Nataraja that starts from the Chola court, moves into the Tamil countryside, and from there begins to radiate outwards into Hinduism at large.

Today, in the collections of practically every Western museum, you will see a spectacular Chola-era Nataraja—because so many of them were produced. And it is so ironic to me that we know what an important symbol Nataraja is, not just in India but in the world. But we never think, ‘Oh, such a ubiquitous symbol must have been an icon of an equally influential and globally significant empire.’

RL: How do you see the role of the queens in Chola empire? How do you compare it to queens in other empires?

AK: In the 10th century, the prominence of Chola queens has no parallel anywhere in the subcontinent. There are a few reasons for this. When the Cholas rose in the 9th century, they were jostling for attention and space with a whole bunch of other power centres. So, Parantaka Chola was intermarrying with all these other power centres. We know that he had 12 wives.

We think that these women were probably sitting around, listening to music, dancing, and playing politics with each other. But these are remarkable women. They are intelligent, educated women who have ideas, who are talking to each other.

You see in their temples that they borrow ideas from one another. You see the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law sharing ideas of how the temple should look. You’ll see the same plinth of lotus petals or band of lions in their temples.

RL: And all this was happening while the men were looking at expansion—all the way to Sumatra and the Gangetic plains to Bengal. There were waves of horses moving, imported from Arabia and Central Asia through the Malabar port. And what really intrigued me was that you write these campaigns into Bengal were more about looting and ravaging than assimilation and conquest.

AK: In some cases, the Cholas were interested in conquest. And in a way, they’re very different from other medieval dynasties.

For example, when they expanded into Lanka, they set up an outpost in Polonnaruwa. Or when they expanded into South Karnataka, they set up an outpost in Kolar. But not in Bengal. And not in Odisha either.

Rajendra Chola himself talks about being a descendant of the sun. He smites his enemies in hot battle and he seizes their elephants, their treasures, and their women. I think it would be intellectually dishonest to pretend that Indian rulers didn’t do these kinds of things.

If you look at the texts produced by the Chola court and the inscriptions commissioned by the kings, they are extraordinarily vivid. They describe a war against Kalinga (Odisha) and how, as the Chola army marched, it dried up rivers. They describe how villages were being set afire, how little flower gardens were burned, and how people were fleeing as the army advanced.

The rulers saw violence as a part of how the world functioned. For a king to be powerful, to be obeyed by his vassals, and to be feared by his rivals, he had to use violence. And we have to remember that a very large army is not easy for anyone to control.

Rajendra Chola himself talks about being a descendant of the sun. He smites his enemies in hot battle and he seizes their elephants, their treasures, and their women. I think it would be intellectually dishonest to pretend that Indian rulers didn’t do these kinds of things. It prevents us from talking about power in a realistic and believable way. It’s not a matter of shame.

RL: Many people in Tamil Nadu and elsewhere believe that the Cholas had a navy. In fact, you say in the book that there’s even a Wikipedia page about the Chola navy. This notion was also popularised by the recent movie Ponniyin Selvan. But in the book, you say that they did not have a navy and instead used their merchant vessels to move armies. How did this work?

AK: We all grew up with the idea that the Cholas were ocean-goers. I remember reading Amar Chitra Katha comics, where there’s this young man whose father is a Chola admiral.

When I started research for this book, I was obviously looking for mentions of ships. When I read the inscriptions, there were all these mentions of army regiments, clearly suggesting that the Cholas loved to document all aspects of their military, political, and religious life.

But I was very puzzled. There’s no mention of navy regiments.

In fact, the great Tamil historian Tamil Y Subbarayalu, wrote a paper about this. He extensively looked at all published Chola inscriptions and found maybe one or two mentions of what might be naval forces based in Nagapattinam, their primary port. But the description is as the ‘Army of the Sea’ rather than naval units. Most Chola inscriptions tend to focus on land-based wars. You see many Chola generals making gifts and temples, but there’s no Chola naval officer.

We’re talking about people who were not royals, but who similarly had this extraordinary idea of expanding overseas settlements. And we know, archaeologically and linguistically, that they pulled it off. To me, that’s the really exciting and amazing story

I would be delighted to see concrete evidence of a Chola navy because it would challenge our understanding of how the Indian Ocean world worked.

The guys who do mention ships quite frequently are Tamil merchants, and we have archaeological evidence from Sumatra, for example. We know that the Tamil merchants had settlements [abroad]. We know that they would charge fees to particular kinds of ships entering their ports. They had remarkable logistical capacity.

They would build using granite imported from Tamil Nadu in Sumatra and Thailand. They were clearly capable of moving very heavy loads and transporting large amounts of material.

So maybe the Cholas didn’t have a navy, but the Tamil merchants did. We’re talking about people who were not royals, but who similarly had this extraordinary idea of expanding overseas settlements. And we know, archaeologically and linguistically, that they pulled it off. To me, that’s the really exciting and amazing story.

RL: Another belief is about this early ballot box under the Chola kingdom. I think it was called Kudavolai Murai. So, is this the origin of Tamil democracy?

AK: While looking at the inscriptions from the medieval period, you see people in Nadu (village) assemblies saying things like, ‘We need to fix this irrigation tank, so we’re going to raise this tax and reduce that tax.’

The specific example [often cited] is from the Brahmin Assembly of Uttaramerur, which is on the way north, as you move up from the Kaveri. It’s perhaps the most comprehensive document we have of how these village assemblies functioned.

RL: So, they were referendums?

AK: They were referendums, they were votes. There were committees for individual functions—an irrigation committee, a garden committee, a temple maintenance committee. You would have rules for who exactly was allowed into which kind of committee. If somebody was on a committee, their relative couldn’t stand for election to another committee.

RL: And then it all came to an end, and not because of Hoysala conquests. The Chola empire came to an end because of tax evasion. When I read that, I was reminded of Al Capone, who was arrested for tax evasion.

AK: Well, we once again have a remarkably clear picture of this through inscriptions. From the 12th century onwards, the nature of the Chola state changes. This is after the brilliant 11th century, when military expeditions were happening left, right, and centre. Obviously, warfare changes the nature of society.

Essentially, what happened in the Kaveri floodplain was that because of multiple generations of war, military men became extremely important and extremely wealthy. And this obviously had a bit of a domino effect.

We have to keep in mind that generations of warfare also lead to raised taxes. We have a lot of inscriptions from the early 12th century where villagers petition kings like Vikrama Chola, saying, ‘There’s been a flood, we can’t pay taxes. Can the burden be lifted?’ Sometimes the court said no, because it had its own expenses to meet.

Essentially, the revenue base of the Chola state, which was once in these villages, was gradually given away to military guys. And then the military guys used various means to make [the land] disappear from the tax authorities.

When a village needed to pay taxes and it didn’t have the money, it had to sell its lands to the people who had money—which is the military men.

So, you very quickly have this situation, from about 1100 to 1150, when military men became massive landowners, buying up temple estates [and village lands].

While villages did not have an option to pay taxes, these military men had connections, which means that they could do tax evasion. And they did this in all kinds of ways. They would say, ‘We will send our armies to fight in battle, and in return, you’re going to declare [this land] tax-free.’ And the kings often agreed. And in a lot of cases, the kings would do that.

Essentially, the revenue base of the Chola state, which was once in these villages, was gradually given away to military guys. And then the military guys used various means to make [the land] disappear from the tax authorities. And so, the base kept shrinking and shrinking.

And by the 1170s, you have this astonishing situation where you see Chola kings making proclamations saying that nobody from this part of the country is allowed to buy land in that part of the country.

You have them saying that they are going to sell off all the lands that have been bought in the last ten years and auction them off to smaller people. But the problem is, there are no smaller people who can afford to buy the land anymore. So you see this escalating agrarian crisis, with people being unable to cultivate and in some cases being sold into slavery.

This created the political and internal convulsions that allowed the Hoysalas and the Pandyas to eventually overpower the Cholas.

RL: And the last Chola king. The inscriptions come to an abrupt end, you say, and many believe that the last Chola king just vanished into the forest. What is your theory?

AK: Well, I think that might have more than a grain of truth to it. Rajendra III ruled for about seven or eight years. There’s all this political and diplomatic backstabbing that happened under his rule. But militarily, he successfully managed to keep his enemies at bay for a little while.

Beyond a point, I don’t blame the guy if he gave up. You have this situation of complete turmoil and chaos, where the men who once owed their land and wealth to the rulers no longer wanted to obey them. They were happy to ally with kings from outside.

I think Rajendra III, after fighting an uphill battle for the better part of a decade, may have simply retired. Because if he had died in battle, we would have heard something about it from his rivals—the Pandyas, for example.

So, when the Pandyas tell us in their inscriptions that ‘the tiger was sent to roar in the forests,’ I think it might suggest that Rajendra III simply gave up the throne and retired to the forest.

RL: You talk about how Tamil became an international language of power and prestige in the 11th century. But later in the book, you also mention how Sanskrit was used for their international campaigns.

AK: You have this interesting situation under the Cholas where, given the importance of democracy in Tamil villages, you have the royals speaking to the villages in Tamil. But in documents commissioned in Brahmin villages, especially, you see them using Sanskrit. These Sanskrit documents are called prashastis—royal eulogies—and they follow a format similar to what you see in other parts of the subcontinent. It’s not just the Cholas, but also the Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Chandelas, and Paramaras.

You have Tamil speakers in South Karnataka, Lanka, Sumatra, Thailand, and as far away as China. This is a very clear sign that Tamil had become international.

International business, finance, and diplomacy were being conducted in Tamil because Tamil merchants were also diplomats for the Cholas.

Also Read: How did taxes work in medieval India? Chola, Mughal subjects struggled like today’s middle-class

RL: That leads me to the last question. You said that they’re so dazzling, so full of colour, that we don’t need to bring fantasy into it. And yet, we are compelled to mythologise history, and, conversely, historicise mythology. As a public historian, how do you see these two impulses?

AK: I think it’s very significant that some of the most influential of all the Hindu texts, the Puranas, are explicitly about the past. But it’s very often told through this complex language of symbolism and allusion, where nothing is exactly as we imagine it.

I think historical literacy makes us see power differently. It makes us see people of the past as human beings, rather than black-and-white figures, heroes or villains.

There’s a cloak of mythology added to various figures. And, of course, this is not limited to Hinduism. You see it in Muslim historical chronicles too. The line between history and mythology is a little more academically defined, but to the people of the past—and this isn’t just an Indian phenomenon, it’s a human one—as memory fades and you move generations and generations away from actual historical figures, you remember them by associating them with legends and stories.

As for the mythologising of history, it’s also, to an extent, a political project.

We live in a time when we have hard historical facts, primary sources, archaeology, and the ability to build these complex narratives of the past. But there isn’t always a political incentive to do that. I think historical literacy makes us see power differently. It makes us see people of the past as human beings, rather than black-and-white figures, heroes or villains.

And I think it’s very important for us, as citizens of a democracy, to be critical about the way we think about power, not necessarily accepting the narratives that power gives us.

In a way, seeing historical people as people, as powerful people who wanted to be remembered in a particular way, humanises it. It humanises our political leaders as well. And I think, at the end of the day, it makes us better citizens.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)