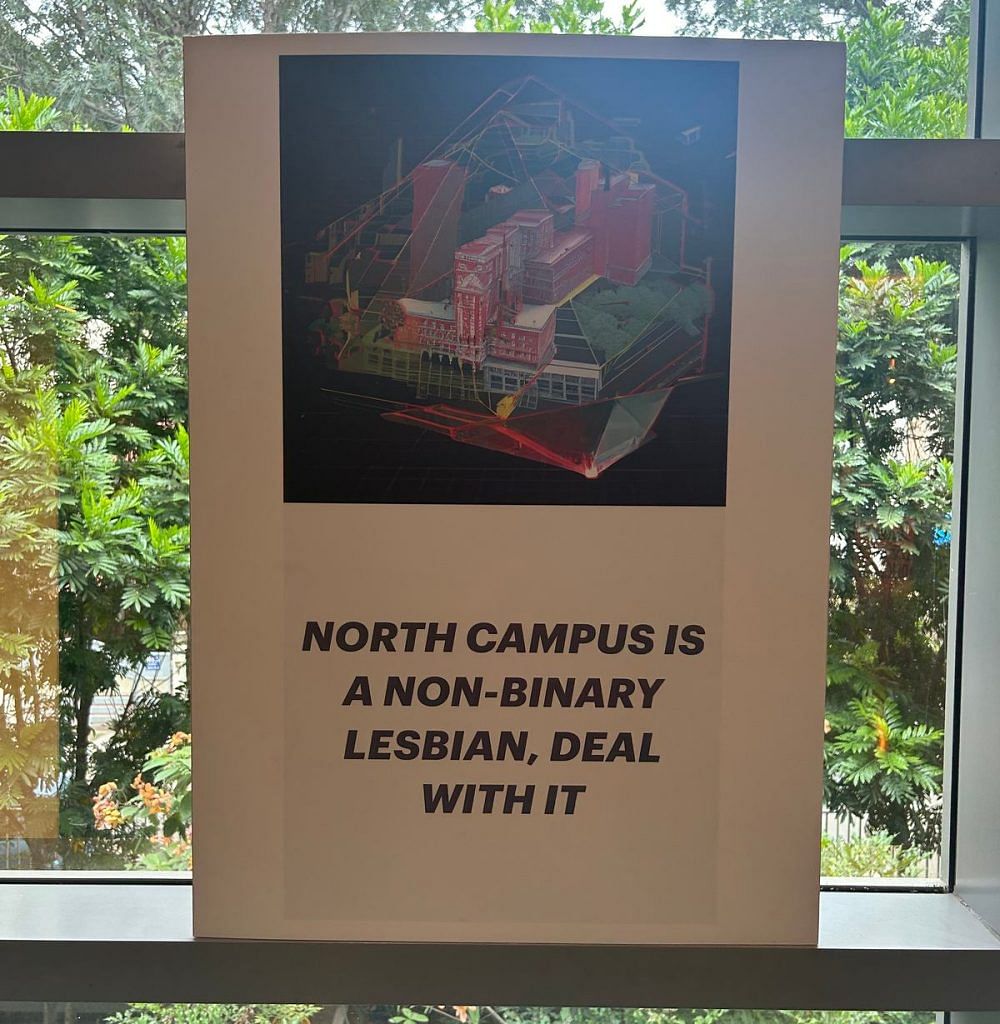

Bengaluru: Imagine that Delhi University’s North Campus is a non-binary lesbian. With this declaration, visual artist and architect Chan Arun-Pina grabbed the audience’s attention at Bangalore International Centre while delivering a lecture on how private and government sectors design university campuses. It’s a campus with ambiguous borders.

The state, coupled with the private real estate market, shapes campus spaces in ways that mirror the control, surveillance, and scrutiny faced by LGBTQIA+ students, argued Arun-Pina, who completed their PhD in Critical Human Geography at York University in Canada.

“Educational institutions are trying to protect their identity and prevent violation of students’ privacy, whereas the state, along with private players, are showing their superiority as they have more financial power,” they said.

This radical reading of modern urban planning caused a stir in the audience.

Arun-Pina used the example of the controversy around the construction of a high-rise luxury complex near Delhi University’s North Campus that sparked student protests back in 2019. In court, DU objected to it on the grounds that the 39-storey complex near Vishwavidyalaya Metro Station would have a bird’s eye view of Miranda House College and its girls’ hostel.

“Such urban planning imposes rigid gender norms on spaces like universities, treating them in ways that mirror societal control over non-conforming individuals,” said Arun-Pina.

It’s a classic case of ‘town and gown’ conflict—tensions between the city and university, they said.

Also Read: What do Manjit Bawa and Abanindranath Tagore have in common? Reinventing miniature art

‘Feminised’ campuses, hypermasculine cities

Arun-Pina’s research comes in the backdrop of queer couples in India fighting to live and love openly.

Although India decriminalised homosexuality in 2018, they argued that there is still no policy to support queer young adults who want to create their own “family.” This struggle continues when queer students move to university campuses as well. In student housing, cis-heteronormative notions of ‘family’ still persist.

“Left unchecked, the expectation of traditional family structures directly affects the higher education of LGBTQIA+ students. They are forced to relive the trauma of growing up queer and trans in cis-heteronormative households,” they added.

Such a fraught relationship between a university and the city is eerily reminiscent of family dynamics. In the housing tower case, Arun-Pina sees the university as essentially feminised, in contrast to the “hypermasculine tones” assumed by the rest of the city, developers, and residents themselves.

Tensions play out at every level. From the city and state, Arun-Pina moved to the personal. They spoke of the experience of a non-binary, queer-identifying former undergraduate student at DU’s South Campus, who observed men in large cars lingering outside the campus, watching students as they entered and exited. Their presence created an environment where the student was forced to adopt more masculine behaviour to avoid being targeted.

“In their experience, the campus was dominated by upper-caste, cis-hetero male students, who enforced traditional gender roles and exerted control over feminine bodies,” Arun-Pina said.

Also Read: Ancient Indian temples were like VCs. Today’s economists should study history

When ‘safe spaces’ become traps

Not everyone was convinced of this interpretation of spatial architecture.

“What would a non-sexist university-city relationship look like?” asked a member of the audience.

To this, Arun-Pina replied that it isn’t only about gender inclusivity, or for that matter, a gender-exclusive hostel in university spaces.

“We need to take a step back and include this very question into architectural planning,” they said.

One way to create “safe” queer space on campus is gender-neutral hostels (GNH). India’s first such hostel was established in 2018, when Mumbai’s Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) reallocated a ground-floor wing of its women’s PhD hostel specifically for LGBTQIA+ students.

But through research and interviews with students since 2020, Arun-Pina found that locating the GNH wing within the women’s hostel automatically subjected queer students to increased scrutiny.

It was a trap that they unintentionally walked into.

“With the reassigning of the common washroom in the GNH wing as now a gender-neutral washroom, open to all genders, the section officer—a cis woman—strategically started using the washroom with the agenda of spying on trans/non-binary student-residents,” claimed Arun-Pina. This research was part of their PhD thesis, ‘Trans Imaging of Non-Normative Homes: The Critical Geographies of Higher Education-LGBTQ+ Student Housing in Delhi and Mumbai, India’, for which they conducted interviews with hostel students.

What was meant to be a safe space for LGBTQIA+ students, soon became the “first place that would be attacked”.

Arun-Pina called for universities to do more than just label spaces as ‘safe’ or ‘gender-neutral’. Instead, they argued that such institutions must seek the help of queer or trans spatial consultants—people with lived experiences and spatial knowledge– for campus planning, including, but not limited to, that of student housing.

“These non-sexist spaces can be anything you want it to be,” they said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)