If the book The Anarchy portrayed the East India Company as a global corporation like Google and Facebook, then the art that the British patronised also had a lot to do with commerce. It is this vast and previously ignored set of commercial paintings by late Mughal artists that historian William Dalrymple focused on for a talk in New Delhi this week – a style and era of artworks that have often been dismissively called ‘company paintings’.

Many of these paintings—created for the East India Company’s pleasure and profit—have never been published or studied critically.

“This is a world which has been orphaned. The British regard it as colonial painting and were slightly embarrassed by it. It was not Indian enough for Indian art historians. So, it’s been suspended in this no man’s land called company school painting,” Dalrymple told a hall full of a fawning, gushy audience at the DAG gallery. “As a result, very, very little work has been done.”

Artists like Dip Chand, Yellapah, Bhawani Das, Rangiah, Shaikh Muhammad Amir, Sheikh Zain-ud-din, Vishnupersaud, Ghulam Ali Khan and Sita Ram created paintings during the critical years between 1790 and 1840. But they did not attract the nationalist attention in Independent India, even though they constitute an important school of art by themselves. They are scattered in different collections around the world or in albums of botanical societies.

And William Dalrymple, author of Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, explained to Indian art lovers how colonialism worked through and with Mughal artists.

Also read: Gandhara, the ancient kingdom that gave world its first Buddha sculptures

Colonialism in action

The city’s well-heeled waltzed in and waited for Dalrymple to arrive at DAG’s new gallery on top of a Lexus showroom in Janpath. There were no empty chairs, some squatted on the floor. Others who leaned on the wall were admonished: “That’s an art piece, don’t lean on it.”

And then the gallery presenter ended up introducing the speaker as “Sir William Dalrymple”. Visitors guffawed. He looked shocked. “Sir?” he asked.

Then he dived right into it.

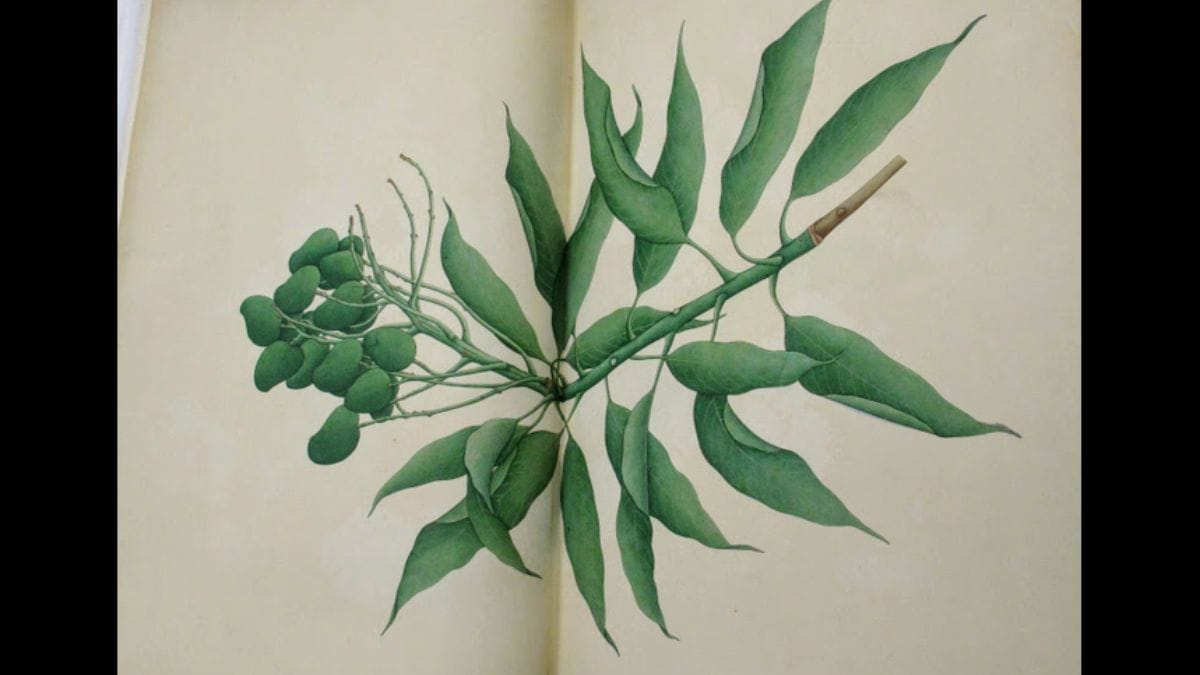

The East India Company, he said, commissioned paintings that combined Mughal miniature style with the Enlightenment-era natural history portraitures. Widespread botanical, geological and archaeological surveys were commissioned in the colonies as part of European scientific enquiry and aggressive cataloguing was launched. It brought out an ‘uneasy and wonderful’ set of hybrid paintings, a curious mixing of worlds where artists used the Mughal mineral pigments, calligraphy kits and English watercolours; painted on imported Whatman paper and produced European-style botanical still lives.

The Mughal artists painted detailed illustrations of local species of plants, birds and animals along with side displays of scientific cross-sections—such as Munna Lal’s Coffee Plant, Bhawani Das’ Green Mangoes, and Vishnupersaud’s Snake Lily. Another of the poppy plant.

“This is a commercial company, so what they are looking at are things they can grow. Could the company make a killing by growing coffee?” Dalrymple explained. “These were scientific works being recorded by a corporation for potential commercial objective.”

Some of these East India Company-commissioned paintings were also the earliest portraits of ordinary Indians. Until then, only rulers and the elite were painted. But Dalrymple calls the early 1800s paintings from the William Fraser album a glimpse into ‘colonialism in action’. They showed rural men from Haryana being recruited as colonial soldiers in James Skinner’s Horse regiment or their land deeds being inspected.

“You can see the measuring of land holdings and processing of taxes,” he said. “And William Fraser taxed heavily and unjustly.”

Fraser, the British agent to the last Mughal ruler’s court, was assassinated in 1835 by a gunman sent by the Nawab of Ferozepoor.

Also read: Hunkaro isn’t an easy play. Migrant workers’ long walk home wasn’t either

Now an imagined dynasty

In 2019, just before the pandemic, the works of these artists finally got public and scholarly attention. They were displayed in a show in London. In May 2022, the National Museum in New Delhi also curated an exhibition called “Company Painting: Visual Memoirs of Nineteenth-Century India”.

But an hour-long talk on Mughal artists can never really be divorced from contemporary Indian politics. And Dalrymple was acutely aware of the day-to-day political developments.

Showing paintings from early 1800s of Mughal constructions in Agra, including the Salim Chishti dargah, he joked: “These were the buildings built by the dynasty that no longer exists. They are a figment of our imagination. The dynasty that never happened.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)