New Delhi: Boredom, before the advent of technology and screens that keep us hooked, was oppressive, even maddening at times. Take this, for instance: When the Belgica, a Norwegian-built ship commissioned by the Belgian government, was “forced to overwinter (spend the winter)” in Antarctica in 1898, its sailors, bound by ice for months on end, found themselves dealing with crushing boredom.

One of them wrote in his memoirs, “We have told all tales, real and imaginative, to which we are equal.” Another jumped offboard, and told his crew members he was walking back to Belgium.

This trying and tiring idleness is further exacerbated in a pandemic that forces all to quarantine at home. Apart from throwing harsh challenges like unemployment, hunger and a crashing economy, the coronavirus pandemic has also tested human proficiency in the art of killing time.

Technology has served us the easier end of the deal, but quarantine wasn’t nearly the same for our ancestors.

To put things into perspective, during the Spanish Flu pandemic that lasted from 1918-1920, a member of a vaudeville acting troupe stranded in Salt Lake City, US, told the Salt Lake-Herald Republican, “We’ve done everything from sightseeing to window shopping, and we’ve done it over and over again.”

They had played blackjack “until the sight of a card fairly nauseated” them, the actor said.

A writer from Ohio, weighing in on the state’s evening lockdown, noted in a local newspaper that life was “just a big vacuum, a great monstrous wad of nothing”.

Also Read: Indians in lockdown find new passion in baking bread, and it’s helping them beat the blues

So much boredom

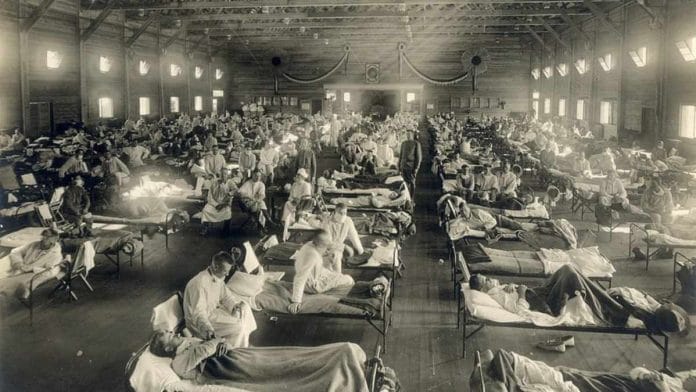

Much like the coronavirus lockdown, the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, which claimed over 50 million lives, left cities under restrictions, with some exceptions. At Hamilton in the US state of Montana, theatres were left open for business, provided customers leave a seat vacant between them.

Meanwhile, bookstores at Wichita, a city in Kansas, US, recorded a spurt in customers. “Wichita bookstores are enjoying excellent trade in magazines,” said The Wichita Daily.

A similar trend was reported from Decatur, Illinois, where people scurried to buy popular magazines. The Decatur Herald & Review reported, “If the quarantine last(s) much longer, the magazine and fireside habit will have such a hold that it will be hard to break.”

At Omaha in Nebraska, US, a group of 100 actors left stranded by lockdown orders eased their boredom by signing up to load and unload salt at a packaging plant.

In the 14th century, countries in Europe, Asia and Africa were ravaged by the Bubonic Plague, also known as Black Death, which is believed to have killed between 75 million and 200 million people.

In his novel The Decameron, Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio referred to certain “merrymaking” during those troubling years. “Some maintained that an infallible way of warding off this appalling evil was to drink heavily, enjoy life to the full, go round singing and merrymaking, gratifying all of one’s cravings whenever the opportunity offered, and shrug the whole thing off as one enormous joke.”

An oddity documented during the Black Death was a “celebration of victory” over the disease by engaging in sex, especially at burial sites. A book titled The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, written by the late American historian David Herlihy noted, “Revulsion toward death and the dead seemed reflected in the feasts and celebrations and merrymaking were common at burials.”

It was said that deaths during the plague were a sharp reminder to survivors of their “own fragile grasp on life”, prompting “some of them to spend their remaining hours in revelry”.

Some orgies at graveyards were also reported at the time. Herlihy’s book noted, “But the orgies that many witnesses describe seem also the celebration of a victory, however temporary, over death. Why else should a favoured site for such behaviour be graveyards?”

At a cemetery in Champfleur, France, in 1394, an official threatened excommunication of those who “dared to dance, fight, throw iron or wooden bars, to play dice or other unseemly games or commit other unseemly acts over the graves of the dead”.

Also Read: Virat Kohli, Karan Johar, Deepika Padukone: Quirky things celebs are up to during lockdown

Out to help

Pandemics take a heavy toll on people, including in terms of employment opportunities, and many people seek to extend a helping hand during trying times.

In the US, a group of actors started working jobs at the American Smelting and Refining Company, and, in exchange for their labour, local charities provided them with meals.

In Edmonton, Canada, a history master’s student founded a “tremendous volunteer network setup” that helped build a grassroots response to the pandemic. Most volunteers were young, unmarried women. They helped nurse those who had contracted the disease, while wearing a cheesecloth mask, changed every few hours.

Also Read: Hair rebellion — from Kautilya, Omar Abdullah to people in Covid lockdown

Dark humour

Such was the scale of death during the Bubonic Plague in the 14th century that a chronicler from Florence noted that all citizens were engaged in burying the dead.

He wrote, “All the citizens did little else except to carry dead bodies to be buried… Those who were poor who died during the night were bundled up quickly and thrown into the pit… They took some earth and shovelled it down on top of them, and later others were placed on top of them and then another layer of earth, just as one makes lasagne with layers of pasta and cheese.”

The grotesque juxtaposition of dead bodies piled together, with lasagna, an Italian delicacy, offers insight into the fact that humour helped many make peace with the harrowing reality.

During the Spanish Flu pandemic, Violet Harris, a 15-year-old American teenager, was rather amused about an advisory requiring people to wear masks in public, as revealed by her diaries. “Gee!” she wrote, “People will look funny — like ghosts.”

Media played an integral role, offering people a platform to vent their frustrations about the Spanish Flu. Many newspapers published poetry, humorous pieces and anecdotes from people who were struggling to come to terms with the pandemic.

One such reader made light of the paranoia among people regarding the transmission of the Spanish Flu. In a poem published in The Winnipeg Tribune, the reader wrote:

“The toothpaste didn’t taste right –

Spanish Flu!

The bath soap burned my eyes –

Spanish Flu!

My beard seemed to have grown pretty fast and tough overnight –

Spanish Flu!”

Also Read: How smokers are getting by without cigarettes in Covid-19 lockdown (it’s helping many quit)

Not a single instance of these activities is from India, yet this columnist would have us believe that ‘our’ ancestors might have indulged in some of them during times, as trying as the present?

Artistic /poetic liberties are best suited for artists and poets….columnists, would do best to stick to recorded facts, and append their opinions as merely those— opinions.