Ghaziabad: The story of the Mughal ruler Humayun being rescued from drowning by a water carrier called Nizam Auliya is the stuff of history books. What’s not so well known is the local lore about how a grateful Humayun built three canopies—the Teen Chhatris memorial—in Ghaziabad as a tribute to the water carrier.

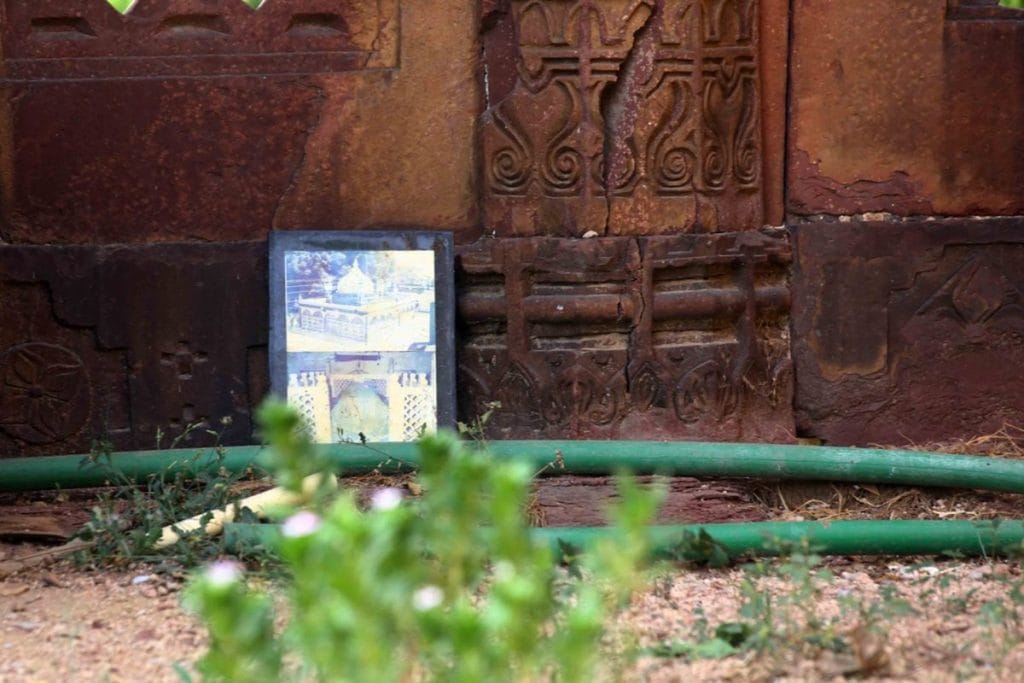

Squeezed between middle-class apartment buildings, the Teen Chhatris are today part of a kabristan, Ghaziabad’s burial ground managed by Mohammad Salmuddin’s family. The canopies are falling apart. Creepers are growing out of their pillars and domes. Blue tilework has mostly disappeared. A fallen dome lies under a heap of debris nearby. He wants them protected by the Archaeological Survey of India.

But as Delhi-NCR historians and heritage advocates such as INTACH zero in on the pavilions for conservation, Muslim residents of Ghaziabad’s Makanpur village are also wary of turning their community burial ground into a historic tourist site.

“We have been approached by NGOs to make it a tourist spot, but how will they do that when the land is registered as a burial ground,” Salmuddin said.

The kabristan has had a recent makeover. It was only in 2020 that Muslim residents came together to clean the dilapidated grounds, plant guava, jamun and lemon trees, place benches, and fortify it with huge walls on all four sides. It is now a living area for Makanpur’s dead.

“Muslims in the locality are scared that if someday this place is turned into a tourist spot, our kabristan will be snatched from us. We do not want any controversy. We want the Teen Chhatris to remain beautiful, and also to keep our kabristan as it is,” he added.

Industrial Ghaziabad’s patch of 500-year-old Mughal history is shielded from prying eyes by a tall green gate marked “Gaon Makanpur Kabristan”, just off Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar Road.

The keys to this gate have been closely guarded by Salmuddin’s family since 2020. On a blistering afternoon, the frail, elderly caretaker adjusts his reflective glasses and asks his son Shahrukh to unlock the gate. And there stand three domed red sandstone structures, the forgotten cousins of the more famous Mughal monuments in and around Delhi.

The family has done what they can, but the structures need professional conservation. Salmuddin wants the ASI to step in before modern developments squeeze the site out of existence.

“We want the government to protect it. We will feel safe,” he said.

Such fears have been bubbling for decades. In the early 2000s, as Ghaziabad’s construction boom gathered pace, the Muslims of Makanpur realised this might be the only kabristan left to them. They formed a committee, the Muslim Seva Samiti Makanpur, and bricked up the boundary before builders could barrel in.

To the left is the roughly two-decade-old Amrapali Green, to the right are newly built apartments, and in front is the sweep of the expressway. The burial ground covers about 5 acres, but Salmuddin claims it was far more expansive before the JCBs and construction cranes started arriving.

“Most of these lands were burial grounds, but then Ghaziabad started developing and all the lands were encroached,” he added.

Also Read: Qutub Minar to Sunder Nursery, Delhi is redefining nightlife. It’s not enough though

Where Humayun meets oral history

Sitting on a metal bench that he and his son installed, Salmuddin speaks fondly about the three pavilions, perched on a slightly elevated corner of the graveyard. “Our forefathers told us stories about these tombs,” he said.

According to local lore, a Mughal king built them to commemorate a bhishti (water carrier) who saved him from drowning.

“The generous ruler made the bhishti the king for a day. When years later the king came back to visit the bhishti, he found out that he had died and built these tombs,” he said.

The family claims several other old graves here belonged to the bhishti’s descendants. Two small ones lie just outside the main platform.

“When we started renovating this plot, we found more graves. The smaller ones must be of kids who passed away in the family,” said Salmuddin. He estimates there are “at least 10-12 graves” in total.

Bhistis, known as sakas locally, were once common in the area, according to Salmuddin.

“They used to carry big leather pouches with water to weddings and other events. They also used to spread water on the newly constructed roads so that the roadbeds settled down,” he added.

Little is known about the chhatris themselves, and their origin is a puzzle. Their red sandstone pillars and latticework resemble the Lodi-era tomb of Yusuf Qattal, a Sufi saint buried in Delhi’s Khirki village, but there’s no evidence linking the two. The bhishti story, however, is more than just folklore. In the Humayun Nama, written by his sister Gulbadan Begam, there is a brief account of how a water carrier saved the emperor’s life.

A translation published in 1902 reads:

“In those days his Majesty had a certain servant, a water-carrier. As he had been parted from his horse in the river at Chausa and this servant betook himself to his help and got him safe and sound out of the current, his Majesty now seated him on the throne. The name of that menial person we did not hear, some said Nizam, some said Sambal. But to cut the story short, his Majesty made the water-carrier servant sit on the throne, and ordered all the amirs to make obeisance to him. The servant gave everyone what he wished, and made appointments. For as much as two days the Emperor gave royal power to that menial.”

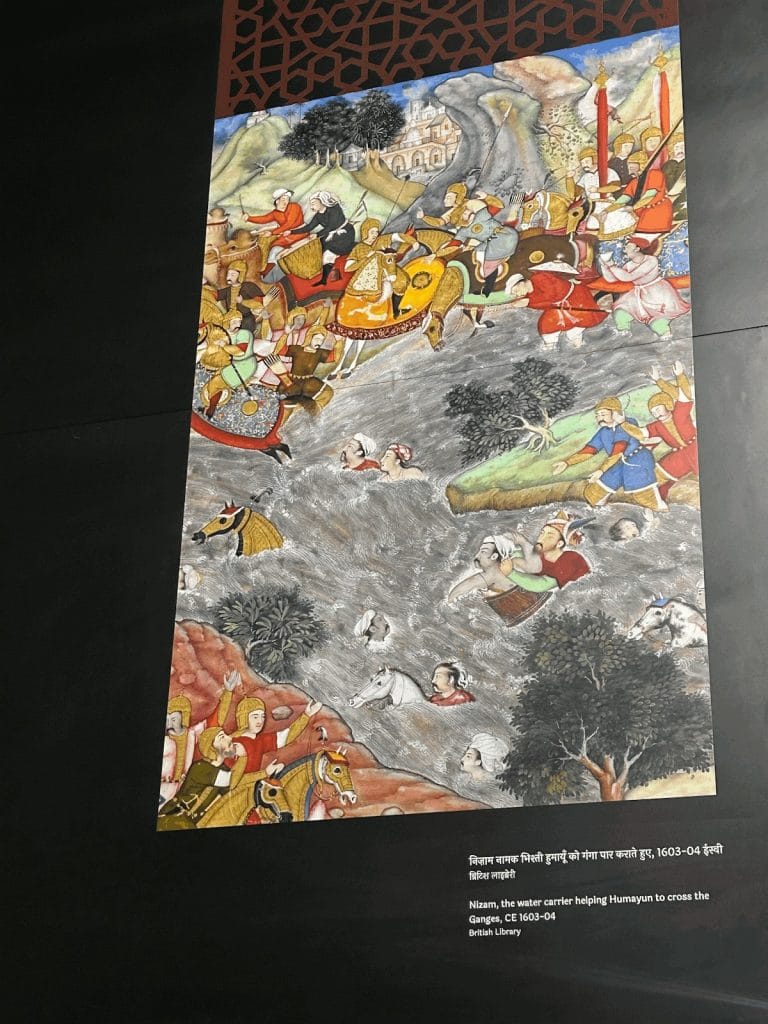

The Humayun Museum in Delhi has a section dedicated to Bhishtis.

“The bhishti was a very important part of Humayun’s life,” said Ratish Nanda, conservation architect and projects director of Aga Khan Trust for Culture. “Even Akbar commissioned two artworks on him that are now displayed in the museum.”

Signage at the museum also notes that after his defeat to Sher Khan Suri in the 1539 battle of Chausa, Humayun nearly drowned while crossing the Ganga due to the heaviness of his armour—“In gratitude Humayun respectfully referred to him as Nizam Auliya.”

What’s not confirmed is the sequel to this story in Makanpur—a series of tombs to honour the bhishti and his descendants.

Nanda said the three structures were built in different eras.

“The jali on the westernmost tomb has a Gujarati influence, different from that of Humayun’s tomb,” he said.

But regardless of their obscure origins, the forlorn tombs are now finally getting more interest from conservationists.

Dreams of restoration

A couple of years ago, INTACH member and history enthusiast Jyoti Ogra learned about an old Mughal site tucked away in Makanpur. Curious, he set out with his son to find it. He immediately realised it could not be left to languish.

“We need to conserve this beautiful Mughal architecture,” said Ogra.

Since that first visit, he’s returned several times and submitted a proposal for restoration. INTACH architects assessed the site and planned a three-phase project: basic repairs, site development, and illumination.

“We made the local people understand that we’d get artisans from Jaipur who’ve worked on Mughal monuments,” Ogra added.

The Teen Chhatris stand on square plinths, each held up by twelve ornate pillars. Each is crowned with a corbelled dome. The middle one is in the best condition and still has an inverted lotus finial, kangura patterns, and remnants of blue tilework. The westernmost dome has partially collapsed. Despite their crumbling condition, all still have delicate lintels, brackets, and inscriptions intact.

It has been almost two-and-a-half years since the project proposal, but preservation work has yet to start.

The ASI, too, is not involved.

“We have not received any requests for conservation till now,” said VS Rawat, superintending archaeologist, Meerut Circle, ASI.

The only improvements so far have been to the surroundings since Salmuddin’s family took over the maintenance of the tomb in 2020. During the Covid-19 lockdown, he and his son built six-foot walls, set up benches, and planted trees that now offer shade to the wilting chhatris.

Also Read: Can Mehrauli Park be like Sunder Nursery? Too many caretakers, not enough care

Ghaziabad’s disappearing heritage

Heritage and history are rarely associated with Ghaziabad. Its most visible landmark is the Ghazipur waste mountain that marks the entrance to the city. For millennials or movie buffs, its claim to fame is Zila Ghaziabad, the 2013 action-thriller about gang rivalries.

Few have any inkling of its Mughal past. Founded in 1740 as Ghaziuddinnagar by Ghazi-ud-din, a general in the Mughal court, the city once had four gigantic gates—Sihani, Dasna, Delhi, and Naya. These ‘Char Darwaza’ are now all encroached upon.

“The four doors that had historic value are gone now,” said Neeta Dubey, INTACH historian. “I have visited two of them and hardly there is any maintenance. They are a lost part of history.”

The Teen Chhatris have survived only because the community came together to protect it.

“Pehle logo ne kabhi dhyaan nahi dia, par ab humein samjh aa gya hai, ye humari dharohar hai” (No one paid attention to the three monuments, but now we know how to value them),” said Salmuddin.

As he walks around the tombs, he picks up fallen leaves and stray bits of litter with his hands, pausing to gaze up at the domes. “Bas sundar bana rahe,” he murmured. Let it always stay beautiful.

Then he points to a faded inscription: “This is ‘Allah’, engraved on all the tombs.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)