New Delhi: It was her first day as the director of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi. Dr Sneh Bhargava’s appointment letter as the first female director of the prestigious hospital and medical college was just getting signed. She was about to make history. She stood in her radiology department, discussing a new case with her team.

Just then, a radiographer barged in.

“The prime minister has come,” she announced.

Bhargava was surprised. “How can the prime minister come unannounced? It cannot be, there is something amiss.”

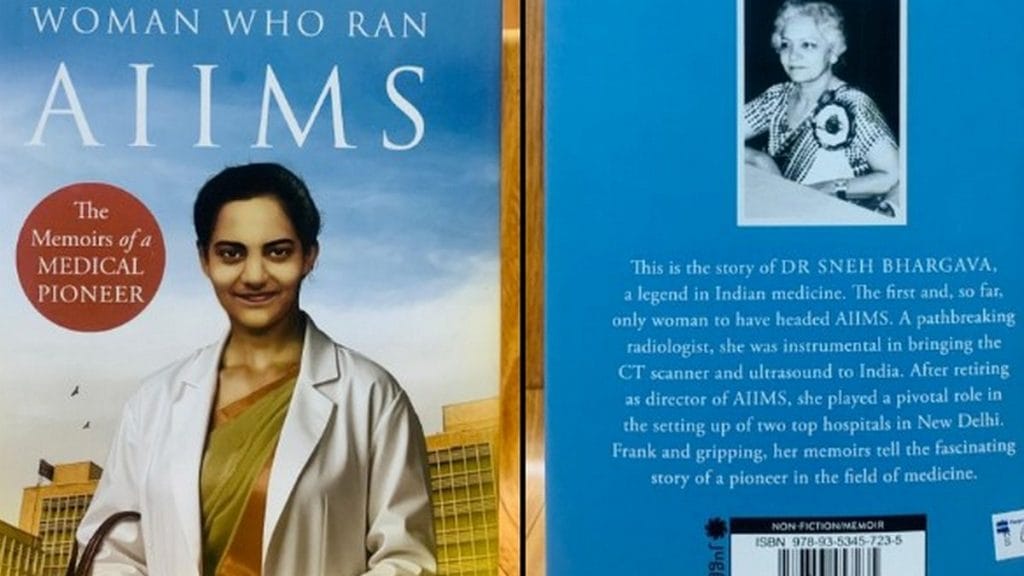

She was right. Bhargava took over AIIMS on 31 October 1984, the day Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her bodyguards. Being appointed woman chief of AIIMS was a landmark, but her memories of the first day are part of the national tragedy too. Now, this flashbulb memory is also etched in her brand-new autobiography, The Woman Who Ran AIIMS—a tour de force of her life, the times, the trials and the triumphs.

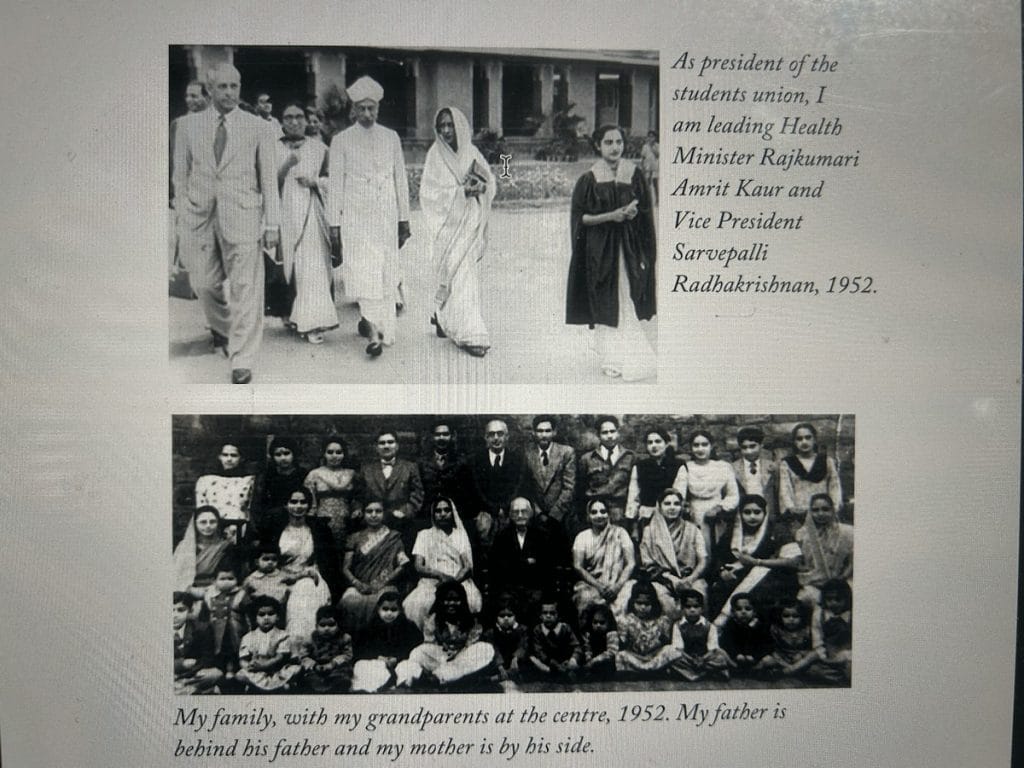

Sneh Bhargava, now 95 years old, was the first and last female director at AIIMS, heading it for six years, 1984 to 1990. It had been built through the AIIMS Act, 1956 by then health minister Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, who had dreamt of an institute that would provide high-quality medical training so “our young men and women could have their postgraduate education in their own country.” Six years after its founding, Bhargava joined AIIMS as a radiographer and made it her life’s mission to honour that dream.

The passage of time hasn’t eroded her memories.

“When I asked where Mrs Gandhi was, the staff pointed to a trolley. I found her wrapped in a blood-soaked saffron sari,” she said, a tremor in her otherwise steady voice. “The first thought that came to my mind after looking at Mrs Gandhi was to put her in a secure place. I rang up the director who was signing my appointment letter, and asked the medical superintendent to shift Mrs Gandhi to the operation theatre.” Bhargava was one of the doctors who wheeled the prime minister to the operation theatre.

A few days later, rumours swirled again in AIIMS and government corridors. Could a woman run AIIMS? Would she still be director after Indira Gandhi’s assassination?

“My friends and colleagues asked me to speak to Rajiv Gandhi. But I was against it. Why should I go? They all said, ‘How will a woman run AIIMS?’ If Mrs Gandhi can run the country as a woman, I can run AIIMS as a woman,” said Bhargava.

Also Read: Filthy toilets, no place to sleep, no CCTV–why night shifts are longer for women doctors

An eye on the future

Her height—four feet 11 inches—belies her commanding presence. She walks briskly to the inner patio of her spacious two-storey house in New Friends Colony. Yoga, she says. On the shelf, there’s a framed photograph of her in vrikshasana, or tree pose. “I like that photo,” she smiles.

Bhargava, whose husband died at the age of 77, lives alone on the ground floor. Her daughter and son-in-law stay upstairs.

She started her career at AIIMS in 1961, and went on to become the head of the radiology department. After her MBBS at Lady Hardinge Medical College, it was a specialisation that chose her in a way when she went for her postgraduate training to London’s Westminster Medical School, now part of Imperial College.

“After MBBS, I was confused about which department to choose. I did a self-analysis, went to each and every department. Somehow, in that process I was invited to join radiology, so I chose radiology. When I joined, radiology was an all-women gang, but as soon as CT scan and other inventions happened, men started joining the department,” she said.

Bhargava makes a case for the value of human intuition and instinct, but is not wedded to the past. She speaks passionately about X-rays as a powerful “second eye” for analysing the human body and welcomes the use of AI in the health sector.

“I have experienced just a little because AI did not come when I was clinically practising, but I know that you will be able to diagnose a little more than what your eyes can,” she said. “You can use AI in certain cases, but not as a routine.”

Curiosity about the new, the novel, and the now are the bedrock of her personality. Upon noticing a selfie stick, she asks a series of questions: “Is this a tripod? What is the difference between a tripod and a selfie stick?”

Students, former colleagues and patients describe Bhargava as a doctor with exemplary skills. But being an exceptional doctor and a patient teacher is not enough to head one of India’s largest hospitals. A director must possess the tact of a seasoned diplomat, the vision of a leader, and the grit of an army chief.

Trials by fire

She proved her mettle during the anti-Sikh riots that followed Indira Gandhi’s assassination. As director of AIIMS, Bhargava had to ensure the safety of her Sikh staff and students and so requested the inspector general of police to deploy a contingent on campus. She also invited two Sikh faculty members to move in with her if they felt unsafe.

As the violence intensified across Delhi, casualties increased, and not everyone could make it to AIIMS or local hospitals.

“I deputed several clinical heads of department from AIIMS to run OPDs in the schools nearest to their homes. In one packed school that I visited, there was no space. I had to stand on top of a desk in the middle and assure all the victims that we would run health OPDs every morning as long as they were housed in the school,” she writes in her book.

ThePrint

She notes in it that writing was something she put off for years. She never kept a journal or diary—only a notebook where she jotted down mistakes so they wouldn’t be repeated.

Under Dr Bhargava, the radiology department at AIIMS transformed. With the help of other doctors, she persuaded the health ministry to sanction a new CT scanner. She then pushed for an ultrasound machine. She also helped establish a blood storage unit and a fertility centre. Bit by bit, she built a stronger department and mentored the next generation of doctors.

Over her three-decade tenure, she oversaw the launch of several new departments: neuroradiology, cardiovascular radiology, oncoradiology, paediatric radiology, and interventional radiology. She helped set up the Medical Education and Technology Center to train students in teaching and was part of the team that founded The National Medical Journal of India. In 1991, she received the Padma Shri for her contributions to medicine.

But there were pressures too. As part of India’s premier medical institution, she had a ringside view of India’s infamous VIP culture on full, unabashed display every day.

“There were more VIP visitors than outsiders. All 544 Lok Sabha MPs and 245 members of the Upper House demanded priority whenever they needed our services. The faculty had to oblige them in addition to their routine work,” said Bhargava.

Former prime ministers Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi were regular visitors. So were Sonia, Rahul, and Priyanka Gandhi. State politicians, often referred by Indira Gandhi, would also land up for treatment, as did VIP patients from neighbouring countries like Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Bhargava recalled one MP who threatened her after she asked security to remove his relatives from a faculty house they were occupying without permission.

“If you evict my relatives, I will break the walls of the hospital,” she recalled him saying. Unfazed, Bhargava stood her ground.

“Sir, the walls of the Institute and my shoulders are not that weak that you can try to shake them. You are on the wrong side of the rules, and as long as I am sitting here, you cannot break the rules and get away with it,” she writes in her book.

In command, with care

Doctors, former students, and staff describe Sneh Bhargava’s tenure as AIIMS director as a golden period. She was a disciplinarian, but she “never ruled by fear”, said Dr Anjan Prakash, who served as a junior director at the hospital in 1990 and is now retired.

“She was a phenomenal radiologist and a leader,” said Dr Nikhil Tandon, professor and head of the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, and Dean (Research) at AIIMS. When Bhargava was director, he was a junior resident trainee.

“She once called three students, including me, to her office and asked us to apply for this PhD scholarship programme in Cambridge. I was the only one who applied, and I got through,” he said.

This tiny intervention made an impression on a young Tandon.

“Any other directors would have just sent a circular, asking students to apply. However, she made an effort to choose three students whom she thought had potential. Today, I can say that she made a significant contribution to my career,” he added.

Even after retiring in 1990, Bhargava continued to support medical colleagues. She helped Dr Suvarsha Khanna, a fellow alumna from Lady Hardinge Medical College, set up the 100-bed Dharamshila Cancer Hospital—now known as Dharamshila Narayana Superspeciality Hospital.

She never lost her innate empathy as she rose through the ranks. At the heart of her work was a desire to help people in need, having faced enormous hardship herself growing up.

Partition to purpose

Bhargava’s childhood memories deeply shaped her outlook toward life. She witnessed the horrors of Partition with her own eyes, travelling with her family by train from Jhelum in Pakistan to Firozpur in Punjab. As the train stopped at Lahore and other stations, she saw a sea of dead bodies.

“All you could hear was shouting and crying,” said Bhargava.

It shaped the woman she grew up to become. Her father, who was in the civil service, continued his duties when the family moved to India.

“My father had set up a camp, and I used to go with him to help,” she said. There, she listened as refugees recounted what they had witnessed—the massacres, the women who jumped into wells to avoid being raped.

“Everything that should not happen was happening. I was given some powder to sprinkle in the camp for people who were vomiting and sick with diarrhea. I thought I should really be able to help such people, that I should become a doctor.”

Becoming a doctor was a calling. In her book, she writes about playing doctor with dolls.

She continues to speak highly of AIIMS and the standard of care it offers. But Bhargava is also worried about how much the system there is stretched.

“I was admitted to AIIMS recently. When a staff member was taking me for a blood test to a different building, the only thing he said was ‘side hato’. AIIMS and doctors there are overburdened with patients,” said Bhargava.

“The only way we can improve the system is by creating a primary health care system. India does not have primary health care providers.”

Also Read: Child bride to doctor—Bengal’s Haimabati Sen traded her gold medals for a monthly stipend

High heels and honours

Even in her 90s, Bhargava maintains a strict schedule—with some adjustments for age. Her early morning walks now take place in the long living space of her house. She walks from one corner to another to meet her daily step goal.

Green tea, coconut water, and home-made khaman dhokla are part of her daily rituals. But her pride and joy is her garden.

A green grassy carpet and summer flowers—pink impatiens, yellow marigolds, purple-white dianthus—fill the space.

“I have worked in that garden. Do you like it? I have put in a lot of effort,” she said.

Bhargava worked non-stop for more than 60 years, but it was in her 40s that she started exploring hobbies like gardening and yoga.

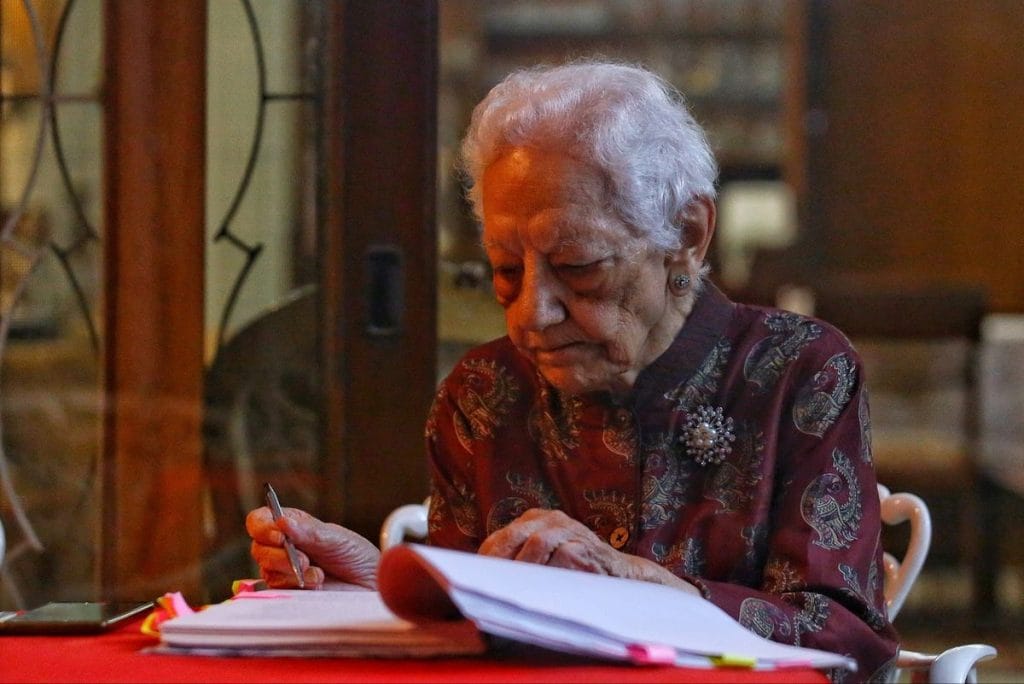

When the pandemic upended life and senior citizens were confined indoors for safety, she decided to write a book.

On a table covered with red cloth, a pencil, a rubber, and a set of pens are arranged neatly. A sheet of paper listing her appointments for the day is encased in a transparent file, along with a marked-up manuscript of her book.

Meetings with her publisher, time slots for media interviews, and appointments with her social media manager are jotted down carefully.

“Every morning, my sari would be laid out on the bed for me by my maid, a pair of high-heeled shoes or sandals (my short stature meant I was addicted to heels) and some jewellery, from which I would choose what to wear. I never counted but I am guessing I must have had over 100 silk and cotton saris,” she writes in her book.

What has remained constant is the heels. She walks around her home in a maroon kaftan and ‘doctor heels’, hands crossed behind her back. But she now finds saris cumbersome.

Her daughter, Anjulika Varma, who runs a travel company and lives on the first floor, stops by to check on her and the two chit-chat.

“Did you finish (the interview), Ma? How was it? Good?” Varma asked, before turning to the weather. “It honestly does not look like it’s May in Delhi. It’s raining. It rained yesterday.”

The house, with its paintings and rugs, is a reflection of her life. An onyx stone came from Pakistan. There are paintings from Singapore, art from China, and a maroon rug with motifs of a sultan on a horse from Kuwait. The drawing room walls are bright with abstract paintings sourced from Kolkata.

The 60-year-old dining table is a family treasure.

“Guess the age of this dining table?” she asked, walking toward it. “It’s from 1959—an heirloom.” Her children and grandchildren have all shared meals here.

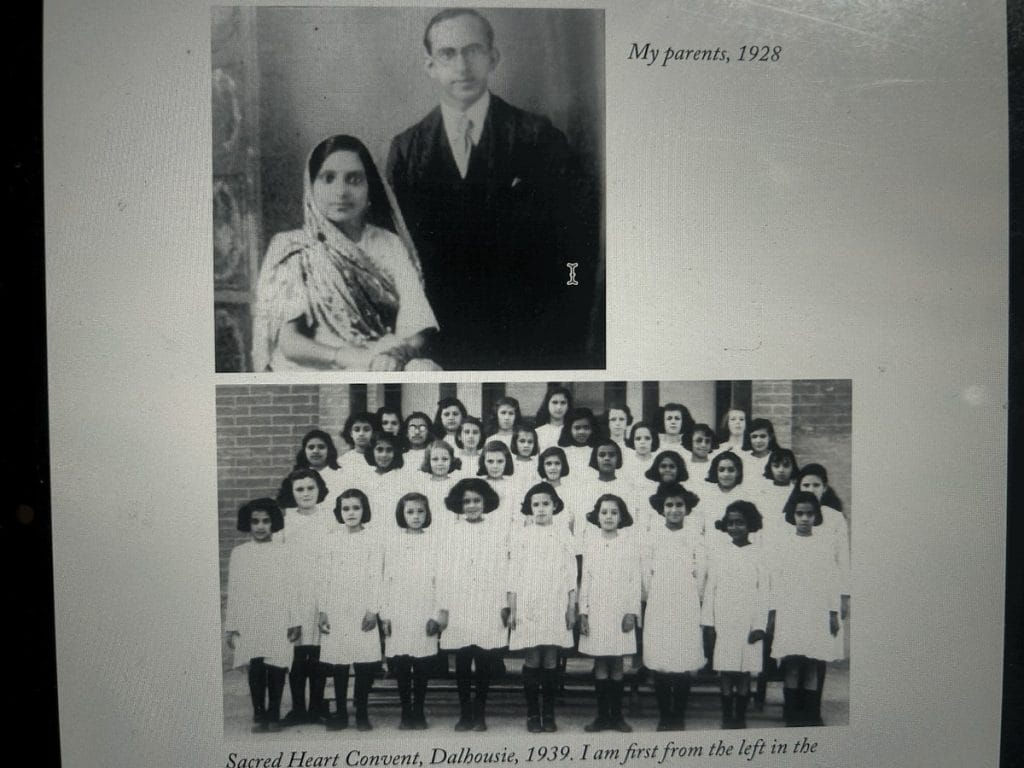

Her study next to her bedroom is filled with personal memories—photos of family picnics, wedding celebrations, portraits of her mother, father, and husband. Her phone gallery is chockablock too.

“Someone had sent me a photo from my granddaughter’s wedding,” she said, taking out her Android phone and opening WhatsApp.

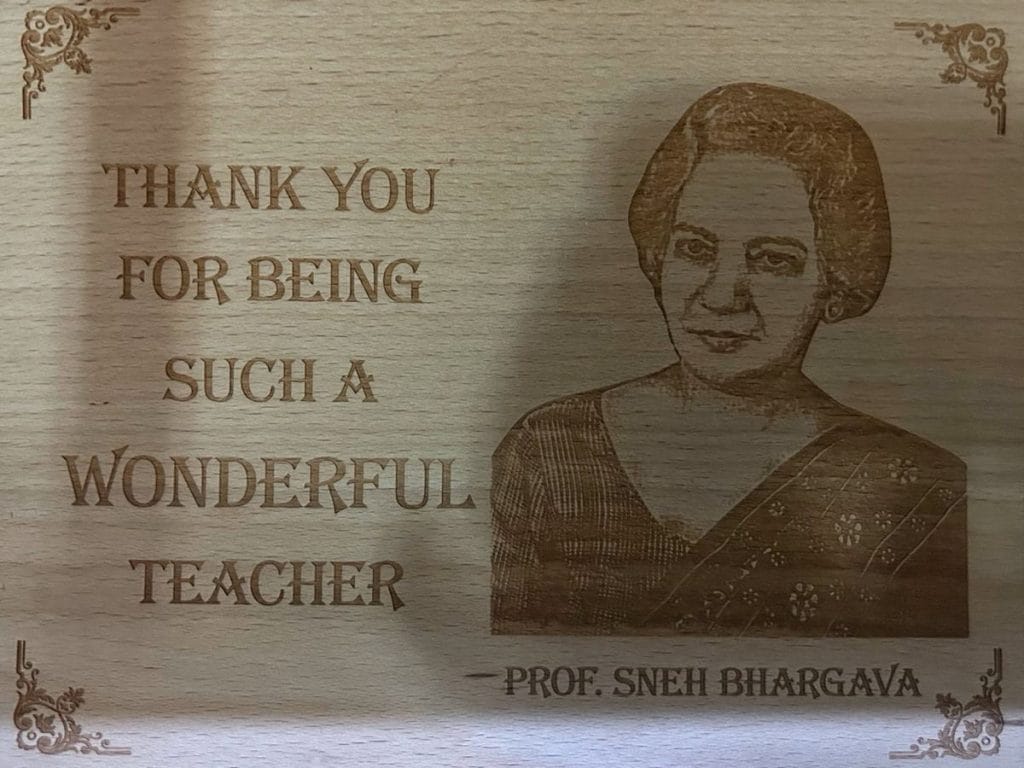

The house is full of photographs, mementos, and lifetime awards. One of her favourites in this maze of memories is a carved wooden plaque gifted by a student. It has an engraved portrait of Bhargava, alongside the words: “Thank you for being such a wonderful teacher.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)