New Delhi: An uneasy quiet ruled the streets of Delhi’s walled city in May 1987. A curfew had been imposed after days of bloody communal riots and the air was thick with fear. But in a windowless room down a narrow lane, a group of friends quietly worked, building an Urdu library book by book.

“In May 1987, during severe communal riots in the Old City area, a curfew was imposed and people struggled for daily necessities. Then, we stepped in to help the residents in different ways, including delivering essentials and creating a library,” said 70-year-old Sikander Mirza Changezi, a founder-member of the library.

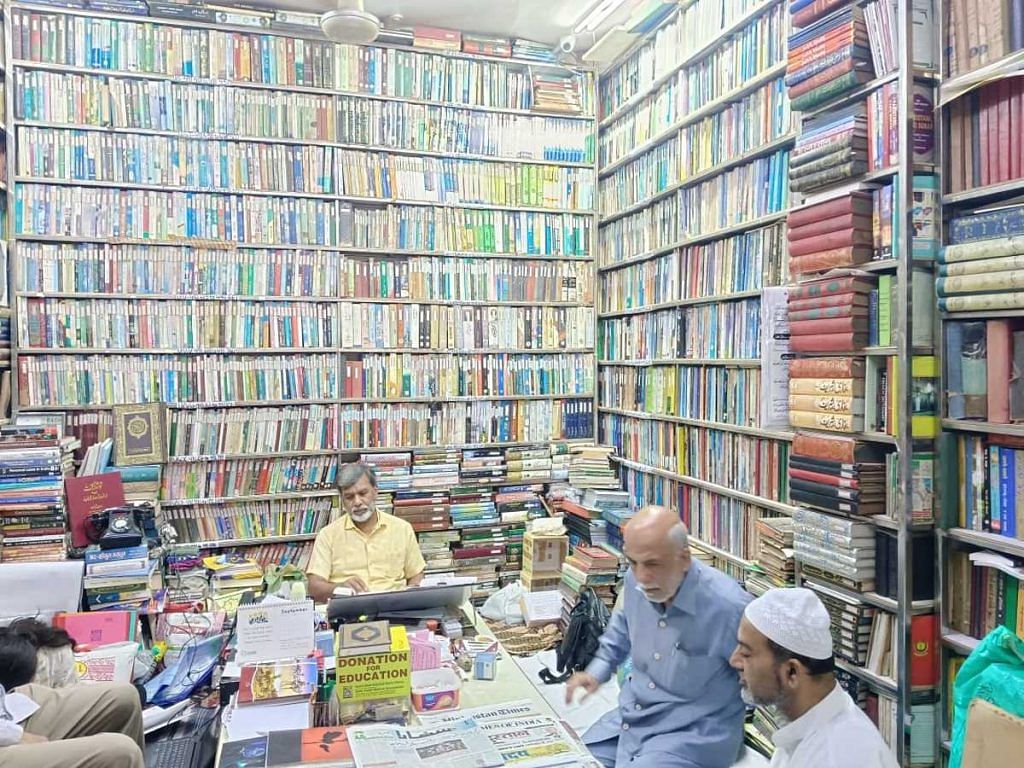

The Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library—one the three major Urdu libraries in Delhi—was born out of crisis, offering calm in chaotic times. Now, nearly four decades later, that same space is bursting at the seams with 30,000 books—what worked during curfew is crumbling under peacetime pressures. The founders are aging, funds are drying up, but the donated books keep pouring in. They want the library to expand and start a new chapter, but it seems out of reach.

Back in those early days, the founders roamed the Sunday book markets in Daryaganj, asking people to donate books they no longer needed. But soon enough, they didn’t have to ask.

“People started contacting us to donate,” said Mohammad Naeem, another co-founder.

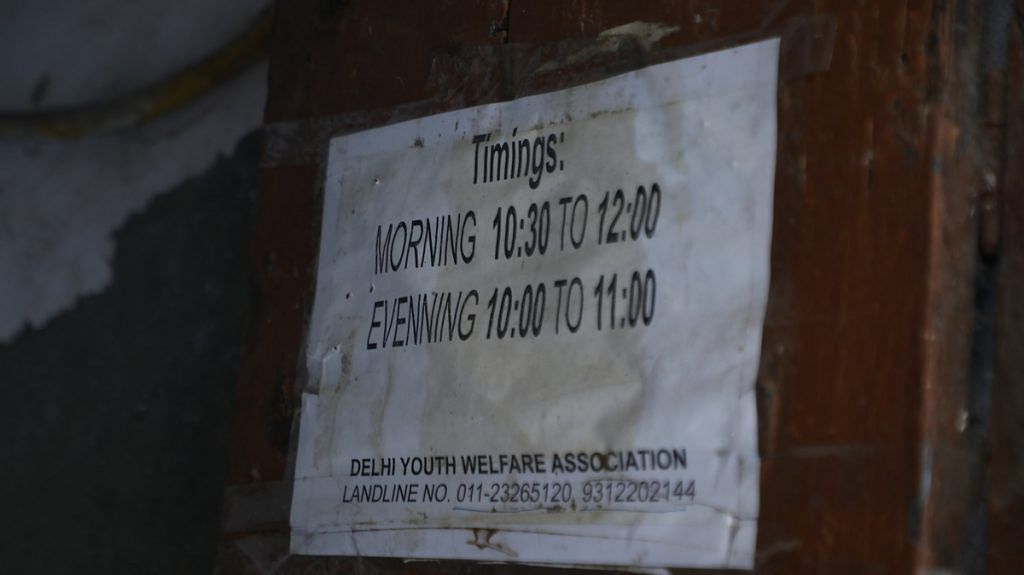

This community support grew into something larger. On December 6, 1990, the group of friends formed the Delhi Youth Welfare Association (DYWA), an NGO to help young people in the walled city. By March 1994, the reading room—once used for cards and games—officially became the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, named in honour of the 18th-century Islamic scholar and translator.

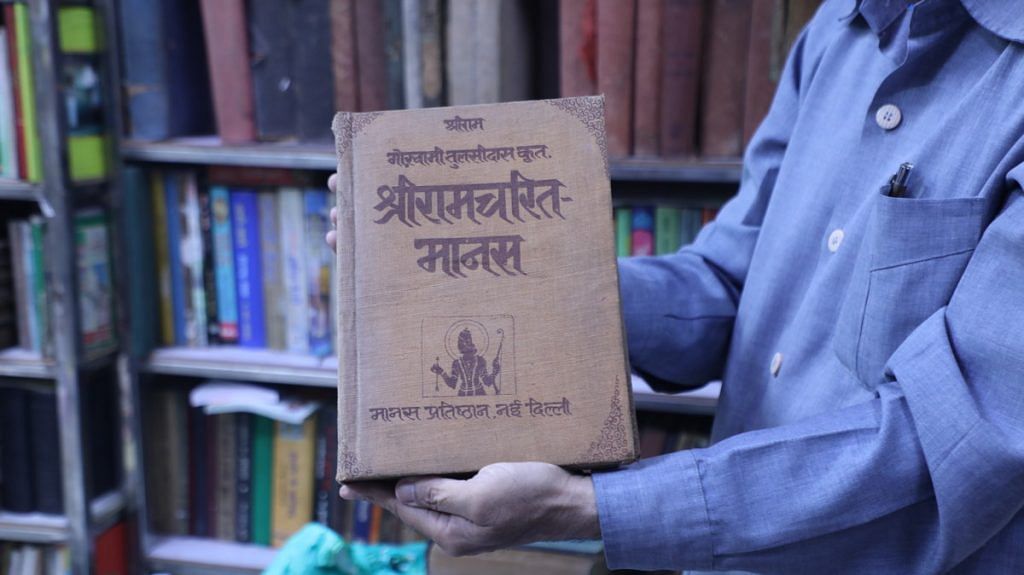

Today, every inch of the walls is lined with Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Hindi, and English books, with many rare and valuable editions among them.

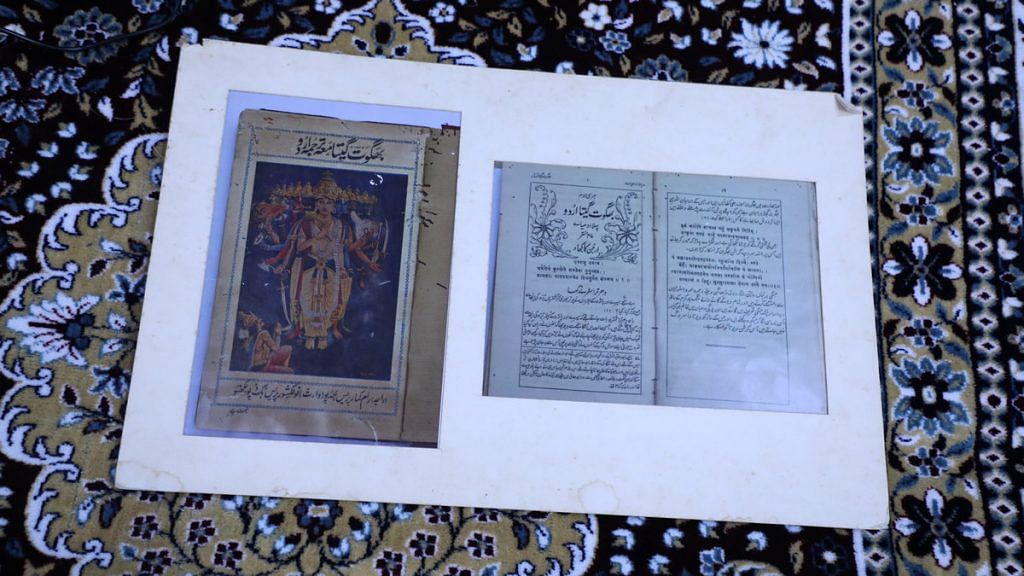

The library’s treasures include a 100-year-old Quran, with each page decorated in a different style and embossed in gold; Ghalib’s Diwan-e-Ghalib, complete with his personal seal and signature; an illustrated Ramayana in Persian; and Diwan-i Zafar, a volume of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s poetry, printed and sealed by the royal press in the Red Fort in 1885.

There’s also a multilingual dictionary by Sultan Shahjahan Begum of Bhopal, a 600-year-old treatise on logic, and rare manuscripts from Baghdad, Beirut, and Saudi Arabia featuring intricate calligraphy.

But right now, it’s too much of a good thing. The library’s success has become its greatest challenge.

“We have no more space to keep the books,” said Naeem. “Just last week, we received over 5,000 books from various donors, and we are still figuring out where to store them.”

Also Read: Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar is dying. Mughlai sells, not Manto & Mirza Ghalib

Oasis for readers, night or day

The Waliullah Public Library is a hidden Old Delhi treasure—it’s difficult to find, but directions are easy to get.

Tucked away at the start of Gali Pahari Imli in Chooriwalan, deep within the maze-like lanes of the Jama Masjid area, this library is well-known to local residents. Even if GPS fails, every biryani seller, butcher, and shopkeeper can point visitors in the right direction.

“People ask about the library all the time. It’s located in a narrow lane and doesn’t have a large sign, so sometimes people miss it or pass by without noticing,” said Aslam, a 37-year-old biryani seller on Gali Pahari Imli.

A nearby butcher chimed in that you have to say the word “library” to get directions.

“Here, ‘library’ automatically refers to Waliullah Shah Library,” he said.

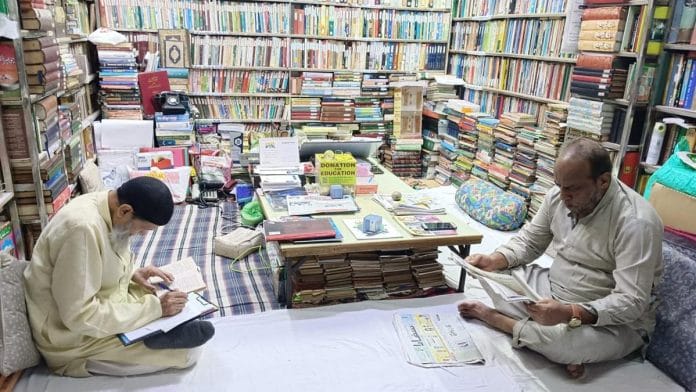

But most visitors don’t need directions. The library has plenty of local regulars—scholars and book lovers who spend hours here, surrounded by a trove of literature, academic texts, religious works, and both fiction and non-fiction, all arranged by language.

“I have been visiting this library for the past 10 years,” said 72-year-old Mohammad Shaheed, sitting in a corner and flipping through an Urdu book on Mahmud Ghazni. “Whenever I feel like reading, I come here and spend about two and a half hours.”

What also sets this library apart is its unique double-shift schedule. It’s open during the day from 9 am to 1 pm and again from 9 pm to midnight, Monday to Saturday.

“We found that many scholars, researchers, and students wanted to use the library after their work or college hours, so we introduced the night library concept,” said library co-founder Changezi. He added that though fewer young people from neighbouring areas visit now, there’s still a steady stream of scholars and students looking for rare books.

Many visitors find the night hours conducive for uninterrupted study or simply because the atmosphere at home isn’t ideal for focused work. Some, like Mohammad Shaheed, simply enjoy the calm after dark.

At 10 pm last Thursday, Taheer Khan, another regular, was absorbed in an Urdu newspaper.

“Having this library in these crowded and noisy streets has given me a peaceful place for my reading,” he said, before returning to his page.

Reading glasses & free tea

There are no rows of desks or neatly divided sections or even chairs at the Waliullah Shah Library. Instead, readers relax on a large carpet with a few cushions scattered around.

If it weren’t for the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, the room could easily pass for a cosy community hall—and, in many ways, that’s exactly what it is. The library is as much a gathering spot as a reading room, where book-lovers come not just to read, but to share stories, discuss books, and enjoy each other’s company.

Beyond its collection of books, the library offers thoughtful complimentary items for visitors. A box of reading glasses in different prescriptions is available for anyone who needs them.

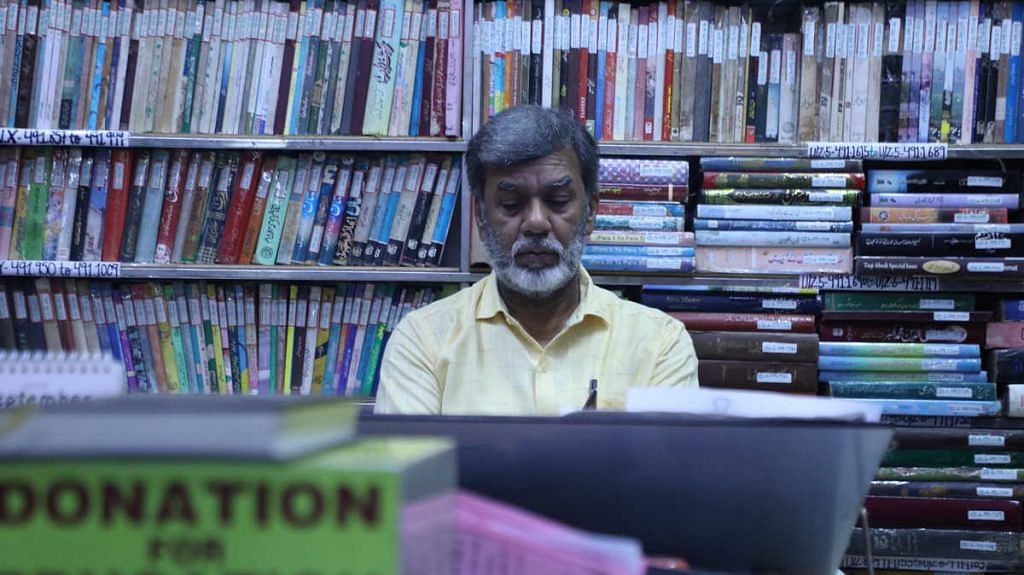

“Often, people come here and realise they’ve forgotten their glasses. So, we arranged to have these available,” said Mohammad Shareef, the 60-year-old librarian and one of the founders, gesturing toward a white box with more than 10 pairs ready to use.

And then, there’s the tea, made on a small electric induction cooktop in a corner of the room.

“We offer tea to visitors who come from far away and spend a lot of time here. It’s become so well-known that now many visitors ask us for it,” Shareef said.

A blank chapter

Building the library has been no small feat. From collecting books to raising funds, it relied heavily on donations and the founders’ personal savings. But now, time is catching up with it. The founders are either approaching retirement age or have already stepped back, and the future looks uncertain with no clear successor.

“Today’s generation is less inclined towards books or maintaining something that doesn’t offer immediate rewards. It’s challenging to find someone with a positive attitude who can take care of all these responsibilities,” said Naeem.

Space is another pressing problem. The small room not only crams in 30,000 books but also doubles as an office for the Delhi Youth Welfare Association, where people come to seek assistance with their children’s education and scholarships.

The founders started building a new branch in Nuh, Haryana, in 2019, and while the infrastructure is ready, it hasn’t been inaugurated yet. Many of the extra books are being sent there, but the founders’ hearts remain firmly in Old Delhi.

“We are actively searching for a space to expand the Old Delhi library because it will remain here; it was established for the people of this area,” said Naeem.

Also Read: Modern Urdu poetry is ‘absolutely merciless’. It changed after Babri

Two other Urdu libraries

Not all Urdu libraries in Delhi are floundering. Just 4 kilometres from the Waliullah Shah Public Library is Anjuman-i Taraqqi-i Urdu (Hind) in ITO, a library with a different focus but an equally valuable collection.

Rather than trying to boost foot traffic, Anjuman has turned its attention to preserving its vast collection of old books and manuscripts through digitalisation. The library has also replaced traditional open shelves with compactor storage units to protect the books from dust and humidity.

Founded in 1903 by educationist and reformer Sir Syed Ahmad Khan to promote Urdu, Anjuman now has branches in both India and Pakistan. Its Delhi collection includes several rare books, including the oldest surviving copy of Fasaana-e-Ajaaib, written by Rajab Ali Beg in 1824 and published in 1865 by Munshi Naval Kishore. It also houses Ketabul Adwiya, an important Persian medical text from 607 A.H., written during the reign of Sultan Iltutmish, and a rare copy of civil laws enforced by the East India Company, published in 1793.

Then, there’s the Markazi Islam Library in Jamia Nagar. Though its nameplate is old and worn, the interior—with separate reading rooms for men and women— is well-maintained and stocked with more than 30,000 books in Urdu, Arabic, Hindi, English, and other languages.

Run by Markazi Maktaba Islami (MMI) Publishers, affiliated with Jamaat-e-Islami Hind and a major publisher of Islamic books, this library offers an eclectic selection. The shelves are filled with everything from religious texts to vintage Pakistani magazines, biographies of figures like Veer Savarkar and Feroze Gandhi, English fiction, and children’s books.

Much like the Waliullah Shah Library, Markazi is a popular gathering place for the neighbourhood’s elders. However, the number of visitors has dropped by nearly 50 per cent in recent years, according to librarian and caretaker Tanvir Afridi.

But he does not see this as an existential threat.

“No matter how much technology advances, nothing can replicate the pleasure of holding a book in hand and reading it,” Afridi said. “The tactile joy of a book is irreplaceable.”

On a Monday morning at Markazi, Shabnam Sayedda, a professor of sociology at Jamia Millia University and a regular visitor for 15 years, was browsing the shelves.

“We even have to pay for e-books these days, but a public library full of religious and literary works is all free,” she said, holding a copy of Status of Muslim Women in India. “That’s why it still attracts people.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Many Hindi and regional libraries are closing. Why the print is not shedding tears for them? Hypocrisy of pseudo secularist?!