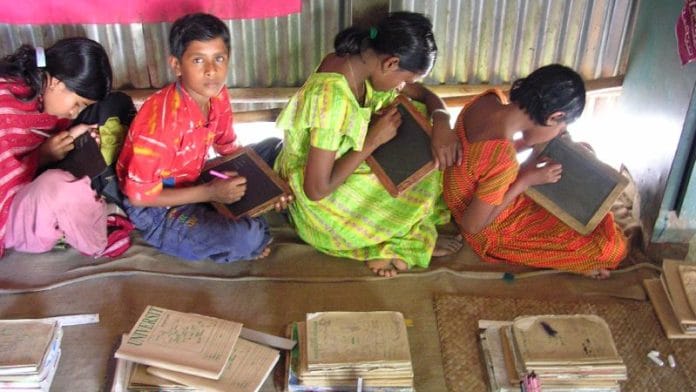

New Delhi: From vaccine hesitancy to political violence, misinformation is a global crisis. A new study, however, states that critical thinking, taught early and locally, can inoculate communities against lies. In 583 villages across Bihar, children as young as 13 gathered in community libraries to learn how to identify and challenge misinformation.

According to a new study—Countering Misinformation Early: Evidence from a Classroom-Based Field Experiment in India—published in the American Political Science Review, simple classroom lessons can effectively combat rumours that cause panic, worsen health crises, and spark violence. Priyadarshi Amar, Sumitra Badrinathan, Simon Chauchard, and Florian Sichart co-authored the paper and emphasised India as a crucial case for comprehending the tenacity and dissemination of lies.

More than 13,500 adolescents participated in the experiment, discovering how to engage their families in conversations about truth and myth. The study found that months after the program ended, participants retained an improved ability to distinguish truth from falsehood and were better at evaluating political information.

“India, where misinformation has led to health crises and to political violence, is a critical case for understanding how falsehoods spread and persist: it represents a combination of low state capacity, shrinking independent media, and elite-driven disinformation in a context of increasing polarization, making misinformation an issue as crucial as it is challenging to address,” reads the study.

Education and the misinformation crisis

Fake news is often seen as a digital-age problem. But in rural Bihar, where information mostly spreads by word of mouth and trust lies with local healers and elders, the danger runs far deeper.

In a few villages, 55 per cent of respondents believed exorcism could cure snake bites, and over 60 per cent thought cow urine was an effective treatment for Covid-19.

To address this, researchers kicked off the Bihar Information and Media Literacy Initiative (BIMLI), which reached more than 13,500 teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18 in the poorest state in India. Students learnt how to recognise false headlines, challenge viral claims, and assess the reliability of sources throughout the course.

“Our educational curriculum, though bundled, focused on MIL and critical thinking… a fundamentally different model from those examined in the existing academic literature: a classroom-based intervention which actively mimics the initiatives policymakers are implementing across the world,” reads the report.

Even the role-playing activities were incorporated into the training to help pupils practice how to react when elders gave them misleading health information. This helped them in overcoming the cultural obstacles of confronting false information without going to court, which is an essential ability in societies where challenging elders is frequently frowned upon.

Also read: 2025 Nobel in economics—what the economists did to win the prize

How classrooms changed minds

Immediately after the programme, BIMLI students showed a significant increase in their ability to critically evaluate information and make informed decisions about sharing news. They also “diminished reported reliance on alternative medical approaches to cure serious illnesses, as well as changes in ability to evaluate the credibility of sources.”

Four months later, researchers followed up with a random sample of students and found that not only had the improvements endured, but students had also expanded their skills to spot fake political news, a topic that the course did not cover.

Even more surprising was the trickle-up effect. Parents of BIMLI students also showed “significantly better ability to discern true from false information,” suggesting the power of child-to-parent influence.

“Educative interventions can have effects that transfer to other important members of networks, thereby adding to a literature that identifies change in adults that stems from children’s behaviours,” reads the report.

Yet challenges remain. Despite higher attendance among girls, only boys showed significant increases in taking action against misinformation, revealing how entrenched gender norms still shape public voice and engagement.

Prior efforts to fight fake news online in India “produced null results,” the report notes, often because they failed to account for local realities of power, trust, and access.

The study emphasises that combating misinformation in low-connectivity environments requires slow, deep learning rather than quick digital fixes.

“If such a comprehensive intervention fails, it would raise serious doubts about the efficacy of media literacy. But if successful, it suggests that previous null results may have stemmed from weak implementation rather than theoretical limits,” the report reads.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)