New Delhi: Naga leader Rongthong Ken shuffles around with a cane, speaks in a near-whisper, and is called ‘uncle’ by everyone. He’s a man of principle and yet leaves behind a trail of blood and mayhem in Paatal Lok Season 2. But the actor who plays him, Jahnu Barua, isn’t an actor at all. He’s a 12-time National Award-winning Assamese filmmaker.

“I have been approached many times to play characters from the Northeast, but I rejected them because they would usually stereotype, and use characters for comic relief and not make efforts to understand the region,” said Barua, who was also awarded the Padma Shri in 2003 and Padma Bhushan in 2015.

Barua’s casting is rare—a complex Northeastern character played by someone from the region. It’s also a full-circle moment. For decades, Barua put the Northeast in cinematic focus. Aparoopa (1982) pulled apart Assam’s liberal elite. Halodhia Choraye Baodhan Khai (1987) exposed rural exploitation and won the Silver Leopard at Locarno. Konikar Ramdhenu (2002) was about a boy trapped in a juvenile home. He even crossed into Hindi with Maine Gandhi Ko Nahin Mara (2005). Now, with Paatal Lok, the Hindi industry is finally turning its gaze to Northeast and meeting him there.

But unlike other actors from the region who got breakout roles — like Merenla Imsong (Rose Lizo) and LC Sekhose (Reuben Thom) — Barua may be one and done.

He initially had said no to Paatal Lok. It was only Sudip Sharma’s script that convinced the reticent 72-year-old to step in front of the camera. It’s an experience he’s not sure he wants to repeat since he prefers the relative anonymity of working behind the scenes.

“I have been chased for selfies and photos after doing the show. It is a big problem now,” said the director, who divides his time between Mumbai and Guwahati. People now call him ‘Uncle Ken’ instead of using his real name. Fans of the show recognise him instantly.

It’s possibly because Uncle Ken is a slow-burn character who ends the show with a sucker punch.

“I did not get him killed. I killed him,” Ken says calmly in one of the season’s final scenes, confessing to a crime that sets off a chain of chaos across the story. It’s a line that stops both Inspector Hathiram and the viewer in their tracks. It’s a “gripping portrayal,” as film critic Devesh Sharma put it, that keeps you “on the edge of your seat”.

The performance is so sharp that it’s difficult to believe that it’s the first time Barua has done a full-fledged role. But for actors who have been directed by him, it’s not such a leap, including Suhasini Mulay, who acted in Barua’s first film Aparoopa alongside Biju Phukan and Girish Karnad.

“I am not surprised that he is also a damn good actor,” she said.

Also Read: From Northeast extra, Chinese secretary to Paatal Lok’s Rose Lizo—Merenla Imsong’s many lives

Tea garden to film school

Barua wasn’t looking to act in Paatal Lok but was requested to audition — a process that all actors for the series had to go through.

“He was kind enough to agree to an audition,” said showrunner Sudip Sharma. “And honestly, Jahnu sir didn’t need much convincing. He read the script, met us, and came on board. He was absolutely wonderful to work with.”

It wasn’t his first time on screen, though. Back in 1988, Barua did a blink-and-miss cameo as a Japanese astrologer in Kakaji Kahin, a TV serial directed by Basu Chatterjee.

“I used to mimic people very well, and Chatterjee had seen that. So I agreed to do the cameo. It was three minutes of screentime,” Barua said, laughing.

He was introduced to films relatively late in life. Born in 1952 in Lakowa tea estate in Assam’s Sivasagar district, he was the sixth of eleven children and had no exposure to cinema growing up. It was only when he joined B. Borooah College in Guwahati for a BSc degree that he found himself drawn to cinema.

“When I watched a few good films, I was attracted to the medium. It wasn’t any one film, but just the kind of impact cinema can have,” he said.

A screening of the wordless satire A Bomb Was Stolen (1962) at the Guwahati Cine Club stuck with him. Directed by Romanian filmmaker Ion Popescu-Gopo, the film’s final five minutes—where love transforms the bomb— blew him away.

“It felt as if 90 minutes of the film could convey something I had never picked up even after studying for hours,” said Barua. He also watched Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali for the first time at the club.

In 1971, Barua applied to both the Lodz Film School in Poland and the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune. He got into both but opted for FTII because of the shorter course. He was an introvert who struggled with a stammer, but the bigger issue was finding the words to explain his plans to his family. He didn’t even tell them when he boarded the train to Pune.

His FTII diploma film was the 17-minute The F Cycle (1974), starring Benjamin Gilami, Rama Vij, and Tom Alter. After graduating, he started his career as an assistant director in Mumbai with Aruna-Vikas on Shaque (1976), a suspense film starring Vinod Khanna and Shabana Azmi.

His own creative aspirations, however, stayed on the backburner for several years. He applied for a loan from the National Film Development Corporation to make his first feature Aparoopa, but it took years to come through. And the actress he wanted to cast for the lead role dropped out because she was pregnant.

“We used to hang around the Adlabs processing lab, and I met Jahnu there,” recalled Suhasini Mulay. “He was about to meet the actress he had finalised for the movie but she was no longer available. He then asked me to play the role of Aparoopa and I agreed.

A Hindi version titled Apeksha, starring Farooq Sheikh, was made alongside it. But it was the Assamese version that made the greatest impact and won the National Film Award for Best Assamese Feature in 1982.

The Aparoopa ‘uproar’

Aparoopa was a breakthrough moment in Assamese cinema. And it was informed by Barua’s own observations of his mother and other women while growing up in a tea estate.

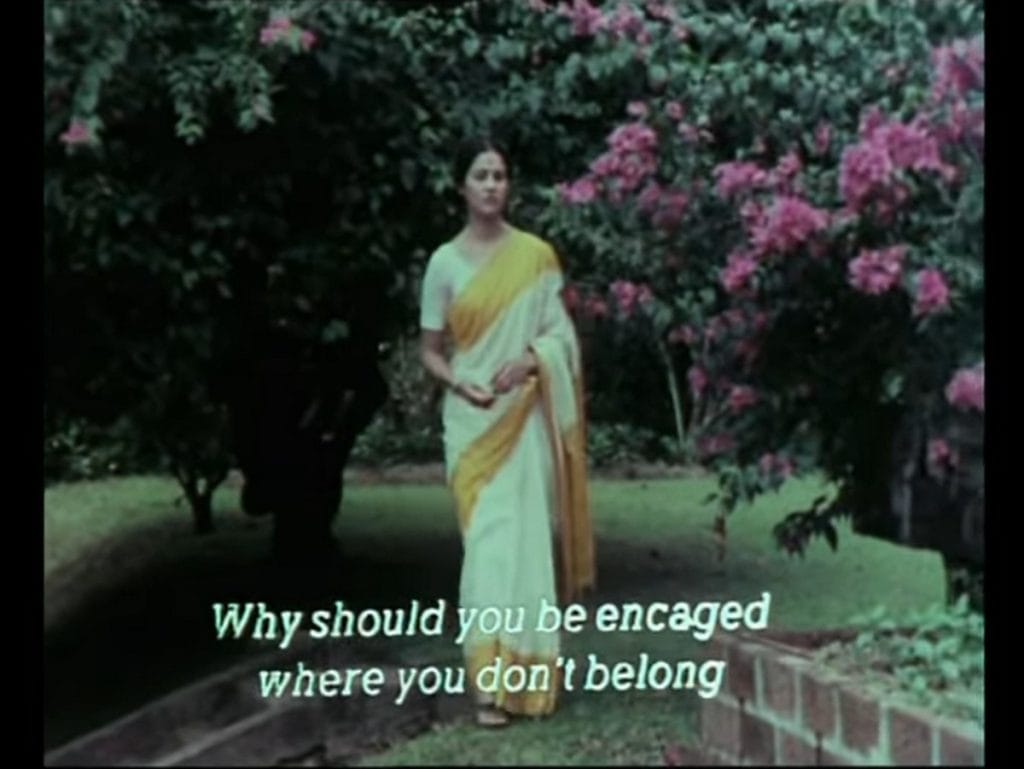

Set in a colonial-era tea garden, the film is about two women: Aparoopa (Suhasini Mulay), the affluent but isolated wife of a tea garden manager, and Radha (Runu Devi Thakur), a travelling theatre actress ostracised by society. Their stories unfold against a backdrop of manicured bungalows and rural labour, drawing out the class divides and gendered hypocrisies that Assam’s “liberal” elite preferred to ignore.

The film shows that even rebellion is privileged. While Aparoopa has enough resources to choose what kind of transgressive life she will lead, Radha’s fate is sealed.

The inspiration for the story came from Barua’s own memories. As a boy, he was confused when a woman in their community left what seemed like a “nice husband.” His strong female characters were also shaped by his mother.

“I saw my mother managing the entire household chores and their families in my childhood,” said Barua, adding she had studied only until Class 2.

Despite being clear-eyed about what he wanted to say, directing didn’t always come easy to Barua.

“He would be very clear in his head about how he wanted a scene to look. But when it came to communicating to us, he faltered. Sometimes he would go quiet in the middle of explaining a scene, and we would wait till he regained the thread and explained it,” said Mulay, who spent months at a tea estate in Margherita where the film was shot, in the peak of insurgency in Assam.

Paired with soulful songs by Manna Dey, Bhupen Hazarika, and Usha Mangeshkar, the film also drew from Barua’s observations of class divides as the son of a tea garden employee.

“I have been an introvert and also used to stammer a lot. So I would go about observing things around me, and the life in tea gardens, which I experienced growing up,” he said.

The film shows the glamour of colonial leftovers—drinking, parties, jeep tours—as well as the loneliness that comes from living a rarified existence. The class divide wasn’t just on screen. Even the crew experienced it, as servers in white gloves lingered around to attend to them.

“In the film too, Aparoopa cannot even make herself a cup of tea without being judged by the servants,” said Mulay. “Suddenly people she called kaku were calling her memsahib after her marriage. And we understood that when it happened in real life.”

Barua layered the film with recurring imager—door frames, windows, rivers—to evoke the restlessness and quiet entrapment of the women’s lives.

One scene that stayed with Mulay was Aparoopa’s uncertain plan to leave with her lover Rana.

“I understood why Aparoopa wanted to leave, but Rana was unsure about eloping. I asked Jahnu why. He decided to leave it ambiguous,” she said.

The film’s themes were ahead of their time, and it provoked both praise and outrage.

“The movie created an uproar,” said Barua. “People were very upset in Assam, because according to them I was ‘breaking up’ a household, and a section of the press attacked me. But I was glad that the film started debates.”

Taking a stand

Barua has never been reticent about where he stands. He pulled Halodhia Choraye Baodhan Khai from the Mannheim film festival because they’d slotted it under “Third World cinema”. He quit the FTII Society in 2015 over Gajendra Chauhan’s appointment. And during the anti-CAA protests, he was one of the few major filmmakers from Assam to speak out.

That mindset shows up in his work as well.

“Cinema has social responsibility beyond making you laugh or cry. I have always been deeply drawn to the human condition,” said Barua, who often uses the imagery of water bodies and birds. While water represents life’s ever-changing nature, birds symbolise freedom.

One of his best-known films, Halodhia Choraye Baodhan Khai, tells the story of Rakheswar (Indra Bania), a poor farmer resisting a powerful landowner. Based on a novel by Homen Borgohain, it’s a spare, unsentimental film grounded in the belief that everyone deserves dignity. It won the Silver Leopard at the Locarno International Film Festival — the first Assamese film to receive an international award.

“There was a tug of war between the Mannheim-Heidelberg International Film Festival and Locarno for my film, because it could be included in only one. But Mannheim had put my cinema under the Third World cinema category, and I decided to withdraw,” said Barua. His decision led to the category being removed from the festival altogether.

Halodhia also caught the attention of Satyajit Ray. Barua said the two met at a film festival, where the Bengali auteur praised the film.

Through the years, Barua has made over 15 films, with many of them exploring hard-hitting themes. In Konikar Ramdhenu, he looked at the state of juvenile homes and child sexual abuse. The 2002 film—the last in a loose trilogy about childhood on the margins with Xagoroloi Bohu Door (1995) and Pokhi (1998)— is an empathetic portrait of vulnerable children in state custody. Barua visited more than a dozen juvenile homes during the process of making it. He found only one warden who genuinely cared for the children — she became the model for the character of Mrs Khatun, played by Malaya Goswami.

“Jahnu was always very aware of what was happening around him,” said Mulay. “Even Xagoroloi Bohu Door looks at what development means on the ground, and the impact on livelihood for people. It is not about how the rich should not be making more money, but how it unfolds for people.”

Another acclaimed film is Firingoti (1992), set during the India-China war. Malaya Goswami won a National Award for her role as Rita Boruah, a widow who starts a primary school in a remote village, much like the one where Barua was born.

“His female characters were very strong and ahead of their times,” said Goswami. “For Firingoti, he suggested I walk barefoot on kaccha village roads and try meditation to prepare for the role. He would always share anecdotes from his own life, and that really motivated me. I have tried to remember his instructions about how to deliver dialogues and act in scenes and I have carried that in my career.”

What also stayed with Goswami was how Barua helped her internalise the character, travelling all the way from Guwahati to Jagiroad just to explain the film.

“I could visualise the whole movie in the three hours we spoke, and I could see myself in the character,” she said.

Also Read: Where is Northeast in Bollywood? India is finally growing an appetite

Hindi crossover

For decades, Barua was a fixture on the festival and awards circuit. But it took a Hindi-language film for him to get mainstream national attention — the critically acclaimed Maine Gandhi Ko Nahin Mara (2005), starring Urmila Matondkar and Anupam Kher.

The film tackled mental health and ageing at a time when these were barely spoken about. Kher played a man with Alzheimer’s who imagines he assassinated Mahatma Gandhi, while his daughter tries to care for him and ease his guilt. The BBC called it “the kind of thought-provoking, non-musical film Bollywood is capable of making but sadly rarely does”.

However, Barua’s second Hindi project, Har Pal, never took off. Starring Preity Zinta and Shiney Ahuja, the film was shelved after multiple delays. It had first caught Priyanka Chopra’s interest.

“She loved the script and was very keen and yet it did not work out eventually,” said Barua. Chopra would later produce Barua’s Bhoga Khirikee (Broken Window) in 2018 — the first Assamese film by her company Purple Pebble Pictures, which has since backed other regional-language projects.

Regardless of language, Barua says he’s driven by one thing.

“I am a humanist, and wherever there is deterioration of human condition, I react,” he said. The Northeast, though, remains closest to his heart and he’s acutely aware of how it’s often misrepresented. Many filmmakers, he said, arrive with a “superiority complex” and little understanding of the region’s people or psyche.

“Even after 75 years of independence, it is extremely unfortunate that we are not represented popularly,” said Barua. “I do not blame just outsiders. Our own political leaders are at fault too. We are a region with an impressive history, and yet most people do not know about it. It feels extremely sad.”

Paatal Lok, he added, may be changing that. “It has created a shift in perspective,” said the filmmaker.

For years, people would ask him whether the Northeast was “safe”. Now, the questions are starting to broaden. Still, he has no plans to stay on the screen.

“I prefer being behind the camera. Let’s keep it that way,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)