New Delhi: India and perfumes have had an intimate relationship. It has shaped Indian culture, royalty, society and even medicine from the Vedic Hindu to the Mughal era. If fragrance is a tool of communication, then perfume is a message in a bottle.

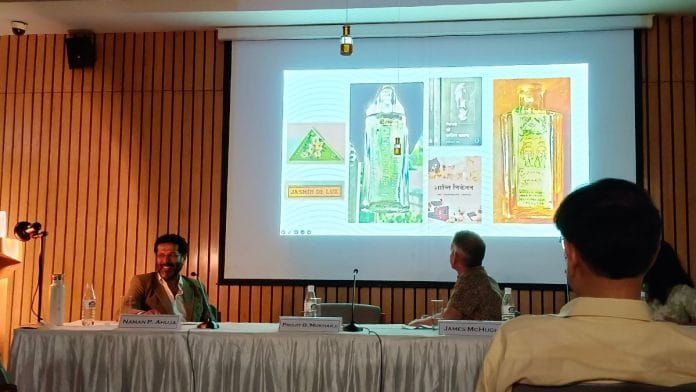

“Fragrance, after all, is communicated through many things and perfume is only one of them. Some need capturing in smoke. That’s the fume part of the word ‘perfume’. Others need to be captured in oil, yet others in alcohol, and some in resin,” said Naman P Ahuja, Professor and Dean of the School of Arts & Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, during a panel discussion on the history of Indian perfumes at the India International Centre’s Kamaladevi Complex in Delhi.

The event was held on 27 March to mark The Marg Foundation magazine’s latest issue, ‘The Histories of Indian Perfume’.

Fragrance is a powerful and private medium of communication. It evokes nostalgia, ignites passions, and makes sense of the intangible. It can transport the mind to familiar haunts— “childhood summers ripe with the smell of mangoes or unfamiliar places like a Nawab’s palace where the smell of aromatic flowers from a royal garden wafts in”.

For a long time, there was no separate perfume for men and women.

“In India, for the most part, perfumes were never gendered. They were the same for both the genders,” said James McHugh, professor of South Asian religions at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles who guest edited Marg magazine’s recent edition. Sandalwood, camphor, musk, saffron and spices like cloves, nutmeg, and myrrh are part of India’s aromatic palette. And perfume makers have gone to extreme lengths to bottle fragrance effectively.

“For some fragrances, we hunt for the anal glands of animals. For others, we gather shells from the ocean,” said Ahuja, who is also the general editor of Marg. The process of capturing each element to make a perfume blend is part of India’s cultural legacy, which according to him, has been “an arena of gross neglect” in the histories of India.

Perfume and art

The ‘marketing’ of a perfume, the shape of the bottle and the imagery associated with it all serve to tantalise the senses. And this is not a modern phenomenon.

The cover of Marg magazine’s latest volume is simple— an image of a hand holding a flower. “It’s a portrait of a king, which was made between 1700 to 1720. The lotus in his hand conjures a certain layering of fragrances,” said Ahuja.

Even the bottles used to store perfumes were important. Attar–makers traditionally used flask-like ‘kuppis’ made from leather hides to store attar. The belief was that leather would absorb any extra moisture, allowing water to evaporate, and only attar in its truest scent would remain.

The physical appearance and characteristics of fragrance bottles, along with the labels and advertisements used to promote them, contributed to the shaping of a certain image of India.

“What they have advertised or how they have been advertised makes a fascinating history of what we have sought to purchase, what desires we have sought to fulfil, what pictures have we associated with those fragrances,” said Projit Bihari Mukharji, head of the history department at Ashoka University, showing some pictures of glass bottles from the 19th century.

One of the images he shared was of a lady on the seashore—her long hair flowing free and unfettered. It was part of an advertisement for fragrant hair oil, promoting a modern notion of feminine beauty that considered unbound hair attractive.

Mukharji pulled out another photo featuring a solid glass bottle that was used to store hibiscus oil (javakusum tel). “These bottles were inscribed in English, Bengali, Hindi, and Urdu scripts, which is pretty rare for that age. This is from around the 1880s and then, we didn’t make glass bottles of this quality in India,” he said.

Also read: Can psychiatry heal wounds of history? Delhi doctors say ‘battle for the mind’ is political

Memories of fragrance

Perfumes, like their bottles, are in a state of flux, changing with trends and taste. The ingredients may remain the same, but they can be mixed to create new fragrant notes and new memories. There’s the push and pull between synthetic and natural fragrances. These days, organic and natural are propelling the industry forward even among big brands.

The perfume industry is constantly changing to reflect people’s preferences, said filmmaker and researcher Malayka Shirazi, who was part of the 2019 project ‘Smell Assembly’ commissioned by the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, which showcased the smells from three Delhi neighbourhoods—Majnu ka Tila, the fish markets of Chittaranjan Park, and the attar shops and spice markets of Old Delhi. In her essay ‘Finding the Ruh Gulab’ for Marg magazine, Shirazi wrote about one of the oldest perfumeries in Delhi, Gulabsingh Johrimal in Chandni Chowk, which is famous for traditionally produced “pure” attars like the ruh-gulab and ruh-khus.

“Today you can go to any big perfume or attar shop and tell them about a fragrance and they will make the same fragrance for you,” she said. But to this day, Shirazi is unable to find the attar her grandfather wore. As she took a trip down memory lane, McHugh fished out a box from under the table. He carefully removed the plastic cover, and the sweet scent of mogra filled the room. Instead of hors d’oeuvres, he passed on sticks with cotton soaked in the smell of jasmine. And the audience inhaled.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)