New Delhi: A century after its publication, a British text about India continues to be hailed as the ‘most compelling portrayal’ of the country’s colonial past.

EM Forster’s poignant portrayal of cross-cultural relationships in A Passage to India and the philosophical depth of the novel still resonate universally.

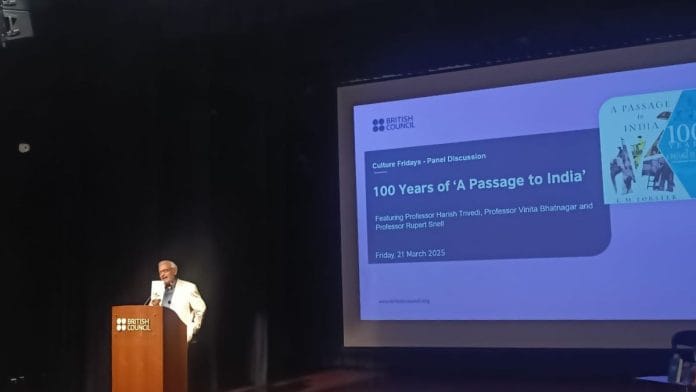

A new anthology, 100 Years of A Passage to India: International Assessments, released in 2024 brought scholars and literary critics to the British Council in Delhi last week to discuss the enduring legacy of this iconic work.

The consensus was that EM Forster’s A Passage to India “is the greatest novel written by a Westerner about India ever.”

Panelists Professor Harish Trivedi, editor of the anthology, professors Vinita Bhatnagar and Rupert Snell, contributors to the volume, came to the conclusion that Forster’s novel endures because it resists being confined to the past. Instead, it continuously echoes in the literature of today, engaging with themes that remain ”shockingly relevant” in contemporary global dynamics.

The authors asserted that the book remains a touchstone for understanding not just the colonial era but the deeper forces of race, gender, and identity that shape human relationships—forces that transcend time and geography.

Bhatnagar, a scholar and novelist, recounted how, even as a Delhi University graduate student in the 1990s, it was reading this book that made her feel truly seen.

“For the first time, I felt like I was studying India, seeing my own country reflected in the syllabus,” she shared.

For many readers, the novel has long provided a mirror to India’s colonial experience. It is also one that is criticised in Indian college classrooms as a novel that exoticises India through an orientalist lens. As a rapt audience sat religiously taking notes, Trivedi, who edited the new anthology, observed that while many British writers have engaged with India, Forster’s portrayal stands apart. It touches on the most fundamental aspects of human connection—particularly the friendships that bridge divides, both cultural and personal.

“Forster wrote the single greatest book,” he said.

Also read: A white woman wants to see real India in Forster’s ‘Passage’. Britain is yet to find it

Limitations of legacy

The story of A Passage to India—which explores the brief yet intense friendship between Dr Aziz, a Muslim doctor, and Cyril Fielding, a British schoolmaster, set against the backdrop of British rule—goes beyond its political context. The narrative revolves around the tension and fragility of human relationships, the impact of social divides, and the complex nature of identity and fraught friendships between the coloniser and the colonised.

Trivedi pointed to Forster’s own experiences, noting that his visits to India and his deep friendship with lawyer Syed Ross Masood—who invited him to the country—formed the foundation of the novel.

Forster sought feedback from Masood, an Oxford-trained lawyer, on the courtroom scene where Aziz is tried for assaulting Adela, a British woman visiting India. Masood’s reply was simple yet pointed: “It is magnificent. Do not alter a word.”

“It’s a very high-class way of telling Foster that if you begin altering things here and there, there’ll be no stopping,” Trivedi noted in wry humour.

Trivedi, in his address before the panel discussion, acknowledged that though the events in A Passage to India unfold within the historical context of British colonialism, the themes Forster addresses remain ever-relevant.

“Forster’s prediction about the division between Muslims and Hindus, and their inability to unite against British rule, proved startlingly accurate — as seen in the Partition of India,” Trivedi said.

One of the most compelling insights from the anthology, he noted, is an essay on the novel’s reception in the Soviet bloc. In Poland, the book was criticised as “too English” and “boring”. And the Russian translator, Lyudmila Nikrasova, faced persecution during Stalin’s purges, reflecting the political tensions around Forster’s work.

And when Trivedi contacted King’s College, the copyright holders of A Passage to India, seeking permission to translate the book into Hindi, they responded rudely, denying his request. Trivedi called it a “very stiff and sniffy letter”.

This snub further highlights colonial legacies within literary culture, sparking ongoing debates about national identity and cultural interpretation.

The novel’s ambiguity, especially in the cave scene where Aziz allegedly assaults Adela, remains a key feature. Unlike David Lean’s 1984 film, which presents it as a hallucination, the novel’s open-endedness invites diverse interpretations, enhancing its timeless appeal, according to Bhatnagar. She also added that Mrs Moore’s transformative experience as she came out of the cave probably has more to do with ageing than spirituality.

Trivedi then startled the audience with the line: “Forster always had a dislike for intellectual women.” Adela was portrayed as a pathetic character, he said.

Bhatnagar interjected, saying she was one of the most grounded characters in the novel.

Also read: Read EM Forster’s ‘A Passage to India’ as a myth. Don’t look for historical accuracy

Timeless relevance

At its core, the novel is a study of human relationships—their fragility, complexity, and the impact of broader social forces.

The themes of racial and gender power dynamics explored in the novel remain strikingly pertinent to the modern era. The trial of Dr Aziz, the allegations made by Adela, and the subsequent court case are powerful reflections of the ongoing challenges India faces regarding justice, gender equality, and post-colonial identity.

An audience member asked how the book should be read today— as a decolonising text or as a colonial one.

There were no specific answers. Appearing on a screen, with his half-moon glasses, Professor Snell pointed out that Forster, who was concerned with the evolution of language, never anticipated the permanent fusion of English with Indian languages. Today, the dominance of English has complicated India’s linguistic landscape, with some Indian languages, like Hindi, being gradually eroded. The consequences are felt by newer generations who may struggle to fully articulate themselves in either language—a concern that reflects a changing cultural identity.

“A certain register of Hindi is losing its lifeblood, with many expressions and idioms fading away. The rise of English has become an overwhelming force, something Forster could never have predicted when he first noticed English’s influence in India,” he noted.

One thing that Trivedi focused on was Forster’s influence on Indian English literature. While he didn’t directly shape the 1930s wave of Indian writers, his support was pivotal. Trivedi recalled how helped get Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable published after it was rejected by multiple British publishers and championed Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi.

Trivedi quipped that Forster himself was not concerned with the labels of “colonial” or “post-colonial.” His work, shaped by his liberal humanist philosophy, is best appreciated by understanding both its historical context and its contemporary relevance.

“A text can be read both in its original context and through our contemporary lens. While postcolonialism is frequently debated, decolonisation should be driven by the native populations of each country, who have always been the majority, as in India,” Trivedi concluded.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)