New Delhi: While India’s diplomatic circle has been focusing on economics, trade, and commerce, the country’s strategic affairs community is yet to evolve at the same pace. For instance, what was pre-1947 India’s relationship with the world? A gathering at the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library in New Delhi earlier this month learned about the significant gaps in India’s history that the strategic affairs community has failed to bridge through research.

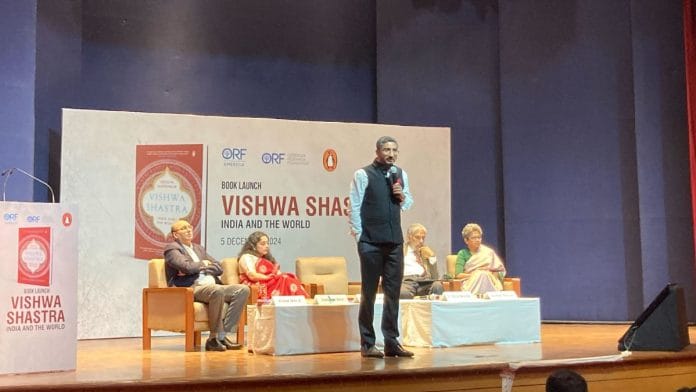

The event was the launch of Dhruva Jaishankar’s first book, Vishwa Shastra, which the author said wasn’t an all-encompassing treatise of India’s history of foreign relations.

“It aims to be a jump-off point for UPSC aspirants or for foreign diplomats coming to India and needing to understand the country,” said Jaishankar, the Executive Director of the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) America, during the near–houseful event.

History, especially pre-1947, is oft overlooked in the field of strategic affairs, according to Jaishankar, a sentiment shared by author-columnist C Raja Mohan, who was part of the panel discussion along with Shamika Ravi, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister, Indrani Bagchi, the CEO of the Ananta Centre, and Ashok Malik, Partner at The Asia Group.

“We do not have enough pre-1947 history. Not many Indian foreign policy thinkers consider it…What we have we need to resurrect, such as focusing on the princely states, the histories of which are stored in state archives,” said Mohan, the former director of the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.

Clearly, Indian strategic thinkers have ignored the history of the country’s foreign relations. However, the Indian Foreign Service has barrelled ahead in learning about economics, technology, and nuclear power—a sign of how fast the role of New Delhi’s diplomatic corps has changed, highlighted Ravi.

Also read: Yuval Noah Harari discusses dangers of AI. Microsoft’s Copilot defends itself

Development of Indian diplomacy

Over the years, India’s diplomatic circumference has grown from its hyphenation with Pakistan. It has defended its right to own nuclear weapons and even developed skills to lobby effectively for deals with countries important to its national security.

With Union Minister of External Affairs S Jaishankar sitting in the front seat, Bagchi, an MEA reporter back in the day, cited a fun anecdote underlining the development of Indian diplomacy: “In those days we used to travel with the External Affairs Minister”—something that doesn’t happen now.

“In 1998, Indian diplomats had to learn how to defend the nuclear tests conducted [at Pokhran]. That was a huge learning curve, especially as the establishment at each level had to learn how to defend themselves,” said Bagchi.

She added that the nuclear deal signed between the US and India in 2005, saw diplomats “actually going out there” to lobby for New Delhi’s interests “in a hostile environment”. In the same period, India had to face numerous attacks by cross-border terrorists and the issue of Pakistan, all of which involved a rapid change in the learning curve.

Here, Malik stepped in and pointed out how India is “more invested” in the world today, especially due to the growth of trade as a part of its economy, all of which provided the environment for change.

This change is slower in the academic world. In his book, Dhruva Jaishankar charts a short path of New Delhi’s interaction with the world, from Europe to Southeast Asia. Pre-Independence India had ties with multiple foreign countries including the Ottomans, the Saffavids, and the Roman Empire, just to name a few recorded interactions.

“There is a long tradition of strategic thinking in India…We have had long interactions with the world. Where there is business, Indians would be present,” said Dhruva Jaishankar.

“India has 1.4 billion people, the largest population in human history. Why is it, however, that universal values are defined by the Enlightenment?”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)