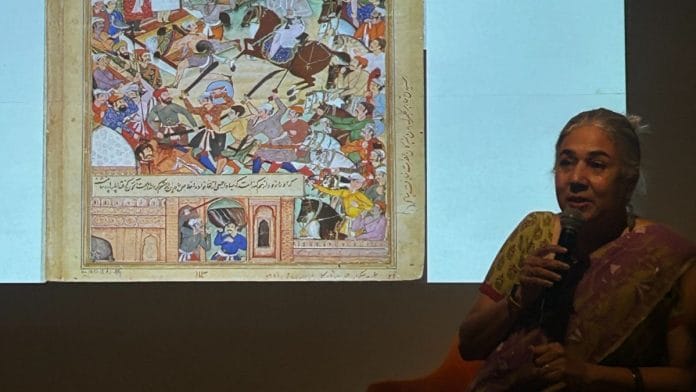

New Delhi: A swordfight rages outside Masjid Khairul Manazil in Shahjahanabad even while shopkeepers sell wares to customers. A lot is happening in the 17th-century Mughal painting from Akbar’s reign.

“But there is not a lot of attention to detail. Perspectives are all over the place, in a two-dimensional space,” said historian and author Swapna Liddle as she took the audience on a visual tour from the reign of Akbar to Shah Jahan and finally the East India Company. Two centuries later, under the Company’s patronage, art had shifted to a single-subject focus, with foreground, shadows, and depth influenced by European realism.

Comparisons between art from the Mughal and Company periods took centre stage at an exhibition of Indian Company paintings at New Delhi’s DAG. The exhibition opened on 28 June with Liddle’s one-hour talk, Imagination to Imprint: The Art of Picturing Buildings from Mughal to Company Style.

Liddle showed how Mughal art styles evolved as the East India Company strengthened its presence in the subcontinent. Early paintings, during Akbar’s reign, did not pay attention to faces and features. But 200 years later, each face in a painting could be differentiated from the other.

By elaborating on the different painting styles, Liddle established that the paintings made during Shah Jahan’s era and later during the early period of the East India Company had a lot of similarities.

“Mughal art began shading into Company art,” she said.

Adding kareena to Mughal art

One of the important paintings made under the patronage of Shah Jahan is ‘The Siege of Daulatabad’, depicting the siege of the Mughals on the hilltop fort of Daulatabad, or present-day Maharashtra.

The painting highlights the fort of Daulatabad on the hill, with the Mughal army in the foreground. It’s a dramatic, full-bodied scene—layered with depth, movement, and detail. The soldiers’ faces are strikingly defined, and the composition plays with perspective to draw the viewer into the action.

Mughal paintings had reached a new level of visual formality and intricate precision. Unlike the earlier, more dynamic compositions of Akbar’s era, Shah Jahan’s court scenes became ceremonial, symmetrical, and deeply layered with meaning, Liddle told the audience.

She added that Mughal era paintings had now moved past two-dimensional perspective, and now had more nuances. ‘The Siege of Daulatabad’ provides multiple perspectives to the viewers, she noted. “It is a similar kind of European trend in which aerial views of places were shown, helping us depict a space with more accuracy to show the different layers of the fortifications, the bastions,” she noted.

The historian added that a greater formality and had come into court rituals and ceremonials with time. “The ways of depicting the darbars became much more formalised now.” At the heart of this was the use of kareena, an Urdu word denoting perfect bilateral symmetry, a hallmark of Shah Jahan’s aesthetic vision. Paintings from this time depict the emperor enthroned under a canopy, seated directly above a central vertical axis, with courtiers shown in strict profile on either side.

One such painting, showing Shah Jahan’s accession to the throne, reveals not only the formality of the event but a shift toward visual documentation.

“It is actually a visual documentation of the important people in the darbar,” Liddle said, adding that each nobleman’s name is inscribed on their robe.

The paintings were not just literal but allegorical as well. Beneath Shah Jahan’s throne, for instance, one painting features a lamb sitting peacefully between two lions, a visual metaphor for harmony under Mughal rule.

“That was a major ideological statement,” Liddle explained. “The idea that peace, which is the result of Mughal rule, is represented through prey and predators sitting next to each other.”

Also read: BJP CM reopens Aurangzeb’s coronation site Sheesh Mahal. ‘Irony, hypocrisy,’ says Congress

EIC’s documentary realism

If Shah Jahan’s miniature paintings captured the grandeur of court life with intricate symbolism, the Company paintings brought a striking shift toward documentary realism, a turn clearly visible in one of the paintings showcasing a map of Chandni Chowk.

The Chandni Chowk naksha is more than a functional guide; it’s a visual record of a lived space, layered with names, elevations, and architectural memory. “All the little buildings also have captions,” Liddle noted. “Each of them has the names of the buildings written next to them.”

One of the most prominent painters from the Company period was Sita Ram, who brought a picturesque aesthetic to the paintings, moving away from map-like representations. His paintings used shadows and depth to create atmosphere, offering layered perspectives, showing foreground, midground, and background, said Liddle. “You can see the bastions and the different layers of fortifications and the river behind it,” Liddle said, pointing at one of his paintings.

Unlike Mughal tasveer or conceptual paintings, Company-era artworks depicting specific locations were called naksha—not paintings, but plans, Liddle explained, underlining how even the vocabulary of art shifted under Company influence.

The most telling innovation about the Company paintings lies in the way space is depicted: not from a bird’s-eye view, but in a hybrid perspective. Streets, like Chandni Chowk, are laid out in plan, while building facades are drawn in elevation, giving viewers a sense of both layout and appearance. “This kind of map is so useful…you see the street, you see what’s on your left and right, and everything is labelled,” Liddle said, comparing its clarity to that of modern Google Maps with street-view icons. The Lahori Gate, the Red Fort walls, canals, gardens like Gulabi Bagh, and havelis like Malik Pira’s, all are highlighted. Many of these buildings are now lost.

As Liddle’s talk concluded, the audience moved toward the exhibition hall, where Company paintings awaited, capturing everything from birds and animals of the era to bustling street scenes, daily life, and architectural marvels frozen on canvas.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)