When food writers Sourish Bhattacharyya, Colleen Taylor Sen and Helen Saberi embarked on a journey to publish The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine, they must have prepared to wade through battles about the origin of rasgullas and butter chicken. But a debate over the inclusion of Mughlai food in their comprehensive encyclopaedia must’ve been unexpected.

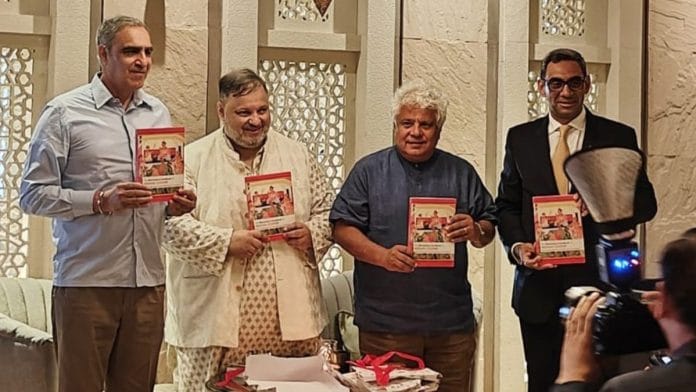

“Colleen and Helen were iffy about including Mughlai food. But the period is so influential for food [that] I told them we can’t wipe out an entire culture,” Bhattacharyya, who is also a journalist, told ThePrint at the launch of their book in Loya, the fine-dining restaurant at Delhi’s Taj Palace Hotel last Thursday.

Their challenge was to keep politics out of food without stripping the country’s distinct cuisines of their identity. But if the discussion about the book with businessman and columnist Suhel Seth was any indication, they succeeded. Politics didn’t taint the rich conversation on food cultures, favourite meals and new culinary discoveries.

Written in an encyclopaedia format, the handbook traverses through states, ingredients and dishes through trivia and history. Seth dubbed the book as India’s food bible, further calling it “a must-have, must-read and must-share.”

Also read: People think Irrfan was intimidating. I want to write about his funny side—wife Sutapa…

Celebrating food, culture, identity

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine, conceived six years ago, is nothing short of a labour of love, painstakingly compiled by 26 contributors and numerous editors.

It tells you about the Indian origins of Gin and Tonic, Chinese Schezwan cuisine’s segue into the world-renowned kitchens of Mumbai’s Taj Mahal Palace, the Harappan invention of alcohol, the many different breads of Goa, and more.

But in an era with “more books about food than functioning traffic lights in the country”, why take on such a gargantuan endeavour, asked Seth.

It was driven by the idea of filling a knowledge gap, answered Bhattacharyya. According to him, the last book of its kind was released 25 years ago — in the form of KT Achaya’s A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food – and our understanding of cuisines has evolved considerably since then. “Everyone in Delhi thought Madrasis would have idli-dosa and Northeastern people have dogs for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

That’s where the knowledge of contributors plays an important role, Bhattacharyya added, citing the example of Hoihnu Hauzel, a journalist and food writer who wrote the sections on Northeast food cultures.

“It’s like an acceptance and acknowledgement of the people’s food and culture. It’ll go a long way in the process of integration” said Hauzel, who is from Manipur.

But food writer and contributing editor Tanushree Bhowmik was absent from this tasteful celebration of culture and cuisine. The presence of Seth, a #MeToo accused, was inexcusable for her. “It hurts especially badly because it isn’t even as if he has a lot to say on food,” she wrote.

Also read: Love in the times of Kargil War, Army tales & traditions at a Delhi…

Generous serving of food trivia

Unfazed by the goings-on of the outside world, Seth’s quick wit and Bhattacharyya’s endless knowledge enthralled the audience. Their banter quickly became a living room conversation between two friends with a deep passion for food.

From memories of railway chicken curry and the challenges of preserving dying cuisines to anecdotes about how a cult classic, Kolkata chilli sauce Sing Cheung, came to be served at Delhi Club House — the audience was served generous dollops of food trivia and histories that went beyond the book.

There were also some hot takes. Bhattacharyya, for one, proclaimed that momo had replaced chole bhature as Delhi’s most iconic dish, and that most of Bengal’s mithaiwalas are actually Biharis.

“Biharis are very hard-working; they’re just very poor in marketing,” laughed Seth.

While the discussion mostly steered clear of politics, Seth lauded how the book revisits and takes pride in food legacies such as Dukes India, rather than “rewrite” them.

There’s so much of our past and present that we can celebrate without getting into a needless debate, Bhattacharyya added.

And while the book does cover the expanse of India’s colourful food culture, from the cuisine of Malabar Muslims to that of Assam’s tribes, Bhattacharyya admits that there are some topics, like beef, that haven’t been explored to their fullest in the book.

“It didn’t matter if I wrote something and got trolled for it; I don’t want anyone to say something about a foreign hand or international controversy as my co-authors are British and American.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)