New Delhi: Sanjay Kumar Prajapati always has an ear to the bowels of the earth, alert to every tectonic groan and moan. And an eye on the world through expansive screens of countries mounted on his office wall. Information reaches him in three milliseconds. “If you even jump near one of our observatories in Tamil Nadu, I could find out about it immediately from this room,” the seismologist says with a smile.

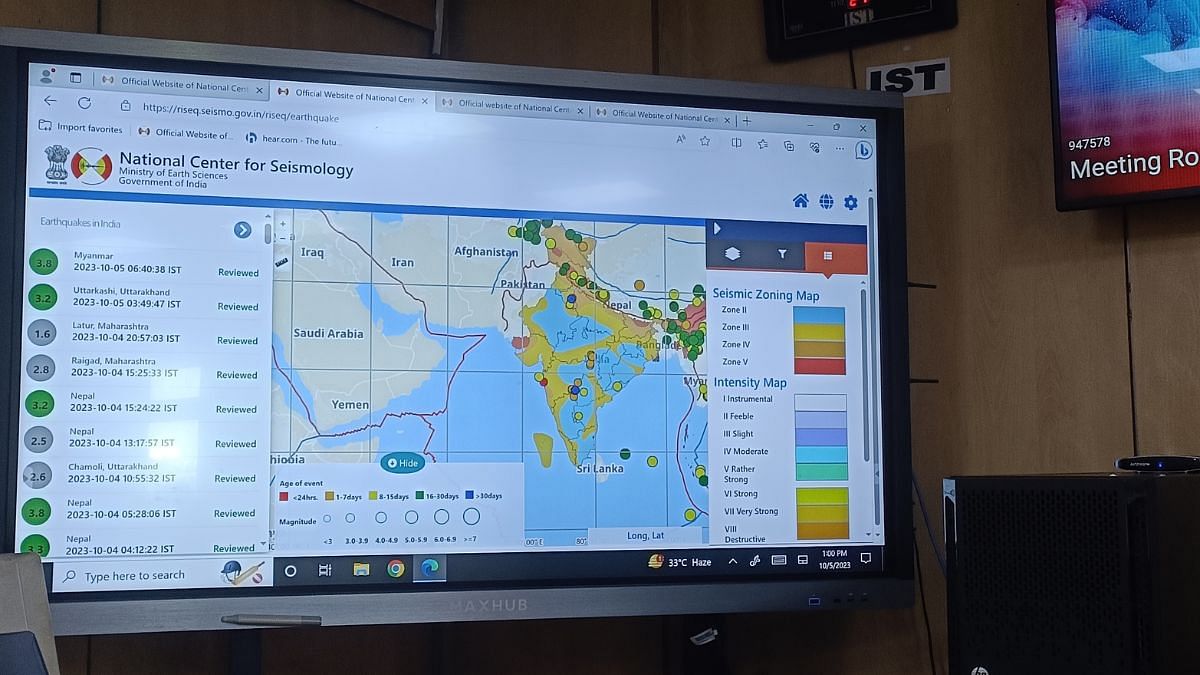

This is the nerve centre of the National Centre for Seismology (NCS), which operates from two floors of a six-storey building in Mausam Bhawan, New Delhi. India’s nodal earthquake monitoring agency tracks every tremor, shake, and rumble beneath the subcontinent. And it is rapidly expanding its scope. From running an extensive network of 157 observatories, it’s currently scaling up its massive micro-zonation project, which will include 30 cities across India from Agra to Thiruvananthapuram.

The NCS is on a mission to revolutionise India’s disaster preparedness one city, town, and village at a time. The Joshimath disaster, which displaced hundreds of people in Uttarakhand, has given an impetus to this project.

“After the Joshimath tragedy, the NCS realised the importance of expanding microzonation studies. Keeping that in mind, cities in Arunachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and a few others from Northeastern states have been added to the existing list,” says OP Mishra, the director of the National Center for Seismology.

Earthquakes don’t kill people, falling buildings do, says NCS scientist Babita Sharma

Suddenly, one of the screens starts blinking rapidly. A bright yellow line resembling a wave appears on the Indian map. People file into the room as their phones ping with alerts. The system has detected an earthquake. But it’s not in India. Within milliseconds, the map shifts to show a yellow spot blinking in Japan—the earthquake’s epicentre. At 5.7 on the Richter scale, the strong earthquake was 10 km deep, but there were no casualties.

“Earthquakes don’t kill people, falling buildings do,” says NCS scientist Babita Sharma. “The world is nowhere close to predicting earthquakes. So, we are doing the next best thing – preventing damage.”

With the ongoing Seismic Hazard Microzonation Survey, scientists can identify hazardous and earthquake-prone zones in vulnerable cities. The final result of the survey is a hazard map that can help policymakers and builders plan limited-risk structures.

“Our job is to ensure there are as few repercussions of strong earthquakes as possible, and that can only happen if we make safe buildings in safe areas,” says Sharma, the survey’s lead scientist.

Also read: Less than 1 in 5 STEM faculty members in India are women, study by initiative on gender bias finds

Mapping the Earth’s heartbeat

India’s pioneering seismic microzonation survey was long overdue, having begun more than 15 years after the 2001 earthquake in Gujarat’s Bhuj killed more than 20,000 people.

The survey started with New Delhi in 2017, when every square kilometre of the city was mapped and studied. The national capital falls into hazard zone IV, only one rank below the ‘most susceptible’ regions, such as Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

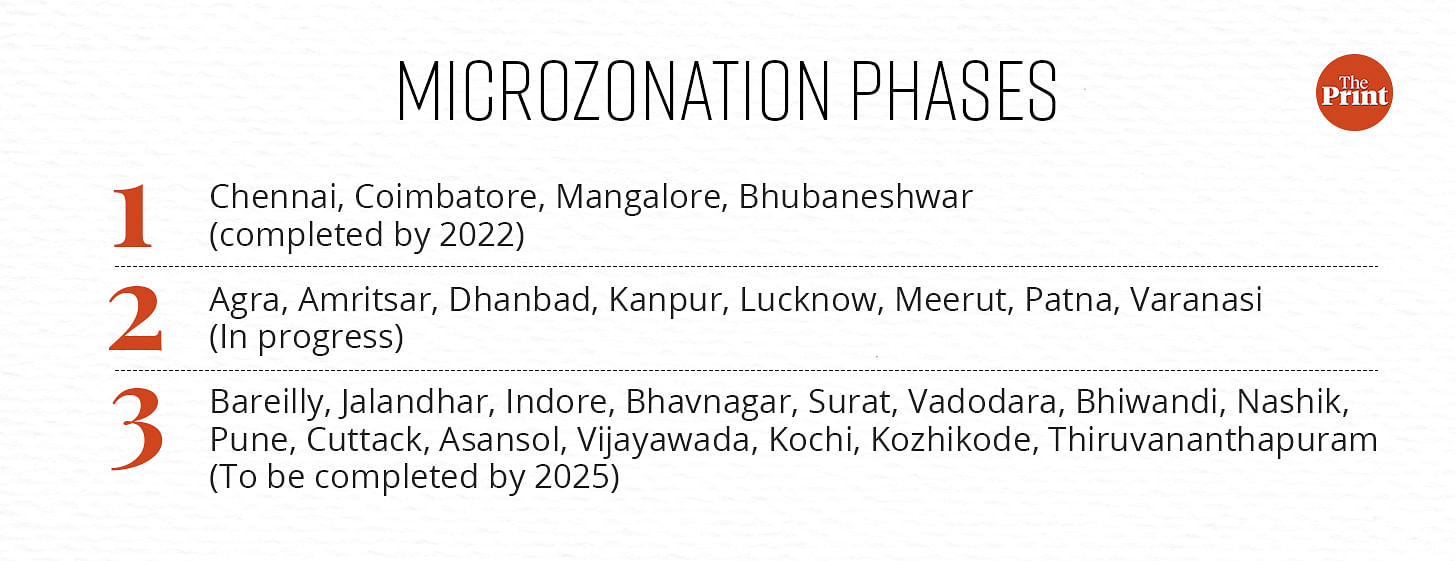

Microzonation was carried out in Chennai, Coimbatore, Bhubaneswar, and Mangaluru in phase one. As for phase two, the NCS team is conducting surveys of eight cities – including Varanasi, Kanpur, and Patna.

“We have strategically chosen cities that fall in III, IV, and V hazard zones, and have more than half a million residents. Microzonation is the only solution to make earthquake-resilient structures in our country,” says Mishra.

As the name suggests, microzonation is a meticulous process where an area is classified on the basis of its geological properties. It assesses ‘seismic risk’ or the possibility of a region suffering damage in the event of an earthquake.

The need for such an exercise is urgent in a country as earthquake-prone as India. The entire northern boundary of the country forms the edge of the Indian continental plate, which is moving toward the Eurasian plate at the speed of almost five centimetres a year. This means the country’s border regions are in the fault zone, the risky area where two tectonic plates meet.

But the scientists are also acutely aware of the limitations of their job. With an ever-growing mandate and a staff of less than 100 people, the NCS has its work cut out. Even then, it’s not the last word on earthquake mitigation policies.

“We can conduct our microzonation projects and prepare our hazard maps. We might even provide advice on where not to construct buildings,” says Sharma. However, it is the Bureau of Indian Standards that is responsible for making guidelines on earthquake-resistant buildings and construction codes. “And after that, it is on the construction companies to follow the guidelines,” she says.

Also read: 100 words, 100 videos, 3 students. New Indian sign language breaks into STEM at CSIR-IMTech

Detecting the risk

The NCS came into its own less than a decade ago. It was part of the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) till 2014 but was later separated to become an attached office of the Ministry of Earth Sciences.

Today, it has over 150 stations with broadband seismographs – the universal tool for measuring activity in the earth’s mantle. All information from these stations travels to the NCS headquarters through a satellite called VSAT, with a delay time of just three milliseconds.

One screen marks every observatory in the country. Another shows a map of India divided into five zones, each indicating a level of earthquake risk.

The NCS uses seismographs with varying sensitivities across the country, and their alert procedures also vary. In New Delhi, for example, earthquakes with a magnitude of two and above trigger alerts to citizens, while the threshold is set at 2.5 and above in all northeastern states.

When the earthquake hit Japan, five different observatories marked on the map started blinking in bright red.

“When at least three observatories pick up seismic waves from an earthquake, our algorithm kicks in. We take the time difference between the first recorded P wave and S wave in each station and convert it into an approximate unit of distance”, says Ajay Pratap Singh, a scientist with the NCS.

With this distance as a radius, the algorithm draws a circle around each of the three observatories. “The point at which all three circles intersect is the epicentre,” he adds.

It is using this method that the NCS alerts Delhi residents about earthquakes as far as Nepal and Afghanistan.

The last alert in Delhi was sent out around 2 pm on 3 October. Two seconds after Sharma felt the ground shift in her office on Lodhi Road, phones pinged. An automated alert, one of her team’s many innovations, told her it was caused by an earthquake in Nepal with a magnitude of 6.2. In the next four minutes, her colleagues had dispatched this information to every concerned authority in the country and shared it on social media as well.

Also read: Drop in stubble burning? Fewer fires this time than 10-year average, says PGIMER scientist

Fast and accurate

As she walks down from her office to the seismograph observatory in the next building – one of the 25 observatories in Delhi—Sharma talks about her team’s field visits to observatories around the country.

A few years ago, while relocating a seismograph in a Gujarat village, Sharma and her team were faced with a perplexing situation.

“The local villagers would not let us remove the seismograph from the observatory, and we were wondering why,” she says. “Turns out they thought it was a machine that prevented earthquakes,” she continues, shaking her head.

The NCS is constantly working to reduce disinformation about earthquakes around the country. From lightning-fast updates to a growing social media presence to an app called Bhoo-Kamp (earthquake), it has increased and upgraded its information-sharing avenues. Now, it is working on a system that sends an automatic alert to NCS’ Twitter account whenever an earthquake is detected, reducing even the few minutes of delay that currently exist.

Moreover, the NCS is also actively involved in creating reports and updates analysing seismic activity experienced in the country. After the 3 October earthquake, the centre released a report within 24 hours, complete with maps and graphs charting the earthquake’s characteristics.

At the foot of the Mausam Bhawan building is an entrance to a basement that houses a seismograph running 15 ft deep into the ground. A rickety, dimly lit staircase leads to a room. Inside are two metal instruments on top of a concrete slab – the seismograph and the accelerograph, which measure the intensity, velocity, and acceleration of an earthquake.

“The concrete slab is our connection to the underground. It is carefully constructed in all 157 stations around the country, with not even one grain of sand or other material,” says Verma, a meteorologist at the centre.

The scientists at NCS are aware of the complexity of their work, and they try to make it easier for people to understand. “Our science is for the people—to make a safer world for them. What is the point if we’re unable to explain it to them?” asks Prajapati. He adds that NCS holds workshops and lectures at different public events to both de-mystify their work and increase awareness.

When a civil servant once inquired about the “increasing number of earthquakes” in and around India, Sharma was quick to correct him: “The earthquakes have remained the same. We have just become better at detecting them.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)