New Delhi: Wills, deeds and legal records hide the secrets of intimacy, desire and love between British men and Indian women in colonial India. But the women, for the most part, were stripped of their identities and their voices. Instead, they were given generic anglicised names like Mary and Polly. So, we’ll never know who they were, says historian Ruchika Sharma.

The assistant professor at Mata Sundri College’s history department examines this complex web of relationships between the Victorian colonisers and their lovers in 18th-century colonial Bengal. And she does it by plumbing the depths of the Calcutta High Court.

The 161-year-old building on Esplanade Row West is not just a heritage moment in its own right, but also houses wills and deeds that go back to the late 18th Century. And this was Sharma’s starting point for her book, Concubinage, Race and Law in Early Colonial Bengal.

“The legal documents carry the heritage of material goods, thoughts, ideas, emotional connections, familial connections and layered and nuanced understandings of mixed-race households,” said Sharma, at a recent talk, ‘Housing the Heritage: The Calcutta High Court and Wills from Early Colonial Bengal’ at New Delhi’s India International Centre.

What struck Sharma was how these legal documents are more than pieces of paper documenting the transfer of property or material be it mansions or jewellery to the women. They are also long emotional notes. The wills she found did not just mention ‘bibis’ and their children but gave details on how they met the men and their domestic lives.

But something was missing.

None of the documents gave the true names of any of the women. This was a challenge for Sharma because there was no way to trace these families or know their current history.

“Everyone else is mentioned by their official names but the bibis (the native concubines) are given popular English names. Not in Bangla or in Hindi, they are always in English. Names such as Mary, Betty, Polly, etc,” she said.

The names may have been given out of love, but in doing so, the men “erased the history of the women”.

Also Read: Between the brothel and Brindavan—Bengal art shows twin faces of Hindu widows after sati ban

Nameless, faithful companions

As she interrogated the court documents, Sharma was drawn into the world of the bibis of Bengal. At the time, Bengal included Bihar, Orissa and Bangladesh. The often unnamed concubines would cohabit with the men who came to India for work or military purposes.

These historical narratives often intersect with the broader themes of indentured labor and migration, reflecting the complex relationships formed during colonial times.

From garden houses, and mansions to rings, 18th-century Britishers in India would leave their material wealth to these nameless ‘faithful companions’. These records kept in the Calcutta High Court are the only links to knowing about these mixed-race relations, said Sharma.

In White Mughals, historian William Dalrymple explores the other side of the repressed Victorian through the love story of a British general and a Mughal noblewoman. Until the 19th century, Britishers would convert to Islam or Hinduism and adopt the local way of life and Sharma takes this forward in her book.

The wills are then markers of history and reflect the social space which both the colonisers and the colonised inhabited. The elite well-to-do men would leave only part of their estate to the bibis. However, the middle class Englishmen, would, when leaving India, leave the entirety of their property in the country to the bibis.

“The only intimate relation they might have had would be with the concubine. The concubine would not just get everything but also be the executor of the wills,” said Sharma.

One will of an Englishman saw his property divided between his Indian bibi and his European mother equally to not leave either his own mother or the mother of his children “destitute”. Another will mentions an Englishman saying that “two of my girls, (both native) now living with me, latter would be left with 1000 sikka rupees and the former with 2000 sikka rupees”.

Many of the wills delineated terms and conditions on the bibis. In instances where the men had to go back to England, they would write, “so much money to be given to my native mistress if she behaves properly”, said Sharma. It reflected their double standards. “The money left to the caretaking woman would only be given to her, if once the man leaves, the bibi doesnot get into improper jobs such as sex work,” Sharma added.

Most of the wills stated that the bibis could have access to the property for their lifetime only. It could not be bequeathed to anyone else. On her death, it would return to the estate of the man’s family.

Also Read: How unique ‘Bazaar paintings’ fuelled trade in colonial India

Markers of marginality

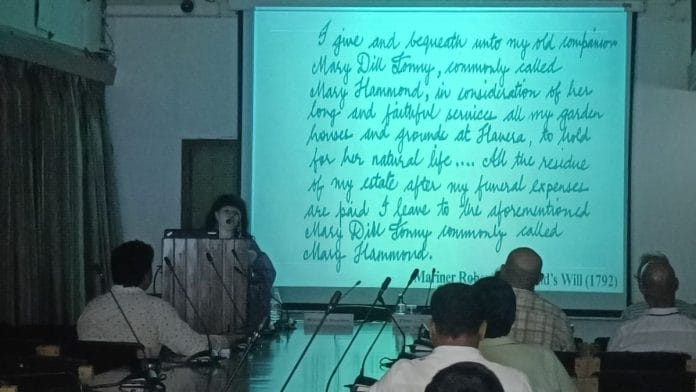

Sharma also read out a few wills to a rapt audience. In some, the bibis would figure as ‘friend’ or ‘affectionate companion’.

“For me, the wills are personal documents. It is a summary of life and what a person may think of near the end of their lives. These documents are important because they bring this unique aspect of domesticity to the forefront. While the sexual and conjugal relations are clear, so is the affection,” she told ThePrint.

There are cases where the bibis contested them, and others where the man’s family would step in to reclaim what they thought was rightfully theirs. And only then, are the bibi’s voices documented. But even so, their names remain anglicised.

When the women weren’t named, the wills referred to them with platitudes such as “my affectionate friend and companion for more than 35 years” and “girl whose care and attention during my illness merits my warmest acknowledgement”.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)