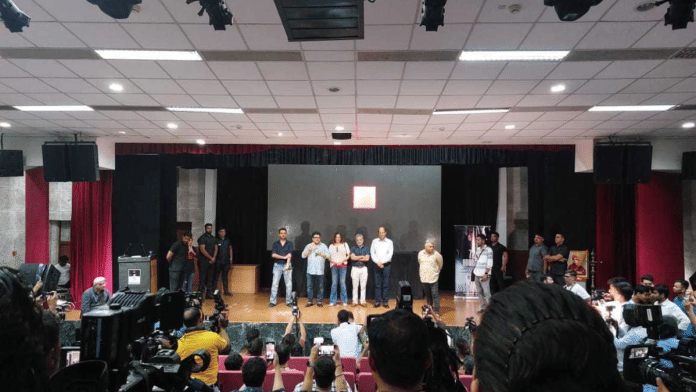

New Delhi: Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University is now a space for alternate movie viewing. It is now holding nationalist studies forums where films are screened and debates and discussions follow. On 4 July, students from various campuses across Delhi thronged the university’s Convention Centre to watch a special screening of the movie 72 Hoorain. Set to be released on 7 July, the film talks about the roots of Islamic terrorism with a focus on Fidayeens’ “ultimate goal” to meet 72 heavenly virgins after carrying out suicide attacks. The screening was organised by a study circle called Vivekananda Vichar Manch, with the aim “to create an alternative to the mainstream ideology prevalent across JNU”.

The event saw loud chants of ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and ‘Bharat mata ki jai’, with director Sanjay Puran Singh Chauhan hailing the change of narrative.

Trailers of other movies and documentaries such as Sahebs: History of Subversion (2022) were also streamed. Evocation of the Army, Swami Vivekananda, Hindu god Mahadev, and Bajrang Dal created an atmosphere that was starkly nationalistic. Chauhan, along with the co-producers, including Ashoke Pandit, joined in, the collective chants echoing across the hall.

Pandit called the screening a “remarkable feat” and congratulated the students on ushering in a change in the narrative in JNU, which has been widely regarded as a Left-dominated academic space. A red screen was put up before the screening, and Pandit saw an opportunity to take a subtle dig: “Ye ladai laal ke khilaaf hi hai (This fight is against Red).”

JNU Students’ Union (JNUSU) president Aishe Ghosh had issued a statement earlier in the day condemning the screening and called it “a misleading event with the sole purpose to communalise and dehumanise a particular community… to disturb communal harmony within the campus.”

The audience took part in a host of ceremonies too, which evoked nationalistic fervour — from lamp lighting to mantra chanting sessions, garlanding portraits of Swami Vivekananda and goddess Lakshmi to singing “Jaag uthe hain soye Hindu”.

Also read: Delhi has a new think-tank for Narendra Modi Studies. Ex-AMU faculty, former critic is…

Loud endorsements, bleak impact

The movie 72 Hoorain is centred around the perils of fundamentalism. Set within a fictional backdrop of an event like 26/11, the movie shows two Pakistan-based suicide bombers, Hakim (Pavan Malhotra) and Bilal (Aamir Bashir), waiting for salvation as promised by their maulana (Fareez Naz) for their sacrifice in the name of being God’s ‘chosen one’. During the endless wait for the gates of heaven to open, the two reflect on their actions and eventually regret them.

Just like Vivek Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files (2022) and Sudipto Sen’s The Kerala Story (2023), 72 Hoorain indulges in stereotyping Muslims — showing the keffiyeh-wearing, bearded man who chants religious intonations before dying and is both the victim and the perpetrator. Pakistan is brought in to complete the picture. What’s more, the end credits even show a Quranic verse in English with grammatical errors.

The movie has been making headlines ever since its trailer was released. Pandit even accused the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) of rejecting the movie’s trailer.

“When you see the film, you look at the dignity and class with which we have handled it. There is nothing that is frivolous. The censor board suggested cuts in the trailer for approval of the film. We argued that no frame is outside the film’s context. If the film can be given a National Award, what’s the harm in the trailer? The contradiction was foolish and laughable,” Pandit says. In a press release dated 29 June, the CBFC clarified that the claims about the board rejecting the film and its trailer were “misleading” and 72 Hoorain was actually granted ‘A’ certification.

On choosing JNU for the first screening, Pandit said that the university commands “a lot of respect”. “Apart from a few incidents that happened there which were quite shameful, we decided to show this film to the students who are the future of the country; that this is what terrorism does and this is how youngsters are radicalised. We saw that anti-India slogans were raised in this place not long back and people who supported terrorist forces were a part of this institute. We decided to screen the movie here to directly debate with the students,” he says.

The idea, according to Chauhan, is to broaden the understanding on terrorism by showing “a different perspective”. The instant reactions of students are vastly different from those in mainstream film circles. “Films that talk about a message or [are based] on a serious issue have now begun to be shown to students. It is a ritual now,” he adds.

Actor Pavan Malhotra, who has acted in 72 Hoorain, passionately defended the movie. A heated exchange erupted at JNU between him and a media personality who asked him whether his shift in choices of films — from Saeed Akhtar Mirza’s critically acclaimed 1989 movie Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro to 72 Hoorain — was a conscious one. Malhotra shared with the audience how he had told Chauhan that “this film should be made” at the time he read the script. He then asked the audience to chant ‘Jai Hind’, castigating those who chose to remain silent.

On its part, the 80-minute-long movie does nothing to ‘debunk myths’ about terrorism — or impress the audience at JNU. For one, it stereotypes Muslims by showing their victimhood mentality in a black-and-white way — quite literally, for that is the colour scheme, along with some substandard animation. Two bare-chested men wearing flimsy white pants and dancing on an imaginary door to heaven failed to appeal to even the staunch nationalists in the audience. The one who had chanted “Jaag uthe hain soye Hindu” most enthusiastically sat yawning. ABVP media head of Delhi Ambuj Mishra said that the movie tried to drive at the notion of anti-terrorism but lost the plot midway. It played into the “politics of lucratism”, he added.

“Perhaps the title aimed to tell you what brainwashing does. It tells you terrorism is wrong and that often, you are brainwashed into it. However, no one needs to be offended since this is what the available literature tells you as well,” he added. “Such screenings are necessary.”

Also read: How Modi brainchild National Forensic Science University cracks it all — crime to infidelity

Not an easy job

Getting a movie screened at the JNU Convention Centre isn’t an easy task. From prior applications, permissions from deans and professors, and a security deposit of at least Rs 10,000, organisers have to run pillar to post in getting the job done. Vivekananda Vichar Manch’s convenor Ankesh Bhati adds that most often, students lack the required amount to hold such screenings. When ThePrint asked her whether PR personnel offer to pay the deposit, she chooses not to answer.

About the 72 Hoorain screening, there’s a bit of push and pull between the filmmaker’s team and event organisers at JNU. While Pandit maintains that it was the students who reached out to the producers to request a screening on the campus—which has led to more such screening requests from colleges such as Kolkata’s Jadavpur University—Bhati asserts that it was the PR who had reached out, requesting for a screening.

The role of special screenings

Bhati, a PhD student at JNU’s School of Languages, defines Vivekananda Vichar Manch as “a nationalist forum for debate and discussion”. It has an established social media presence and a Facebook and Twitter page too, she adds. And the 72 Hoorain screening isn’t the first film event she has organised. She was part of a small-scale screening of The Kashmir Files in February 2022 at JNU’s Ganga Dhaba, which gathered a relatively small turnout. In May this year, she helped organise the screening of The Kerala Story, which attracted a larger audience. And, by far, the one at 72 Hoorain was the largest, she says.

Bhati had organised a screening of Sen’s 2022 documentary In The Name of Love! on the alleged conversion of Hindu and Christian women in Mangaluru. And despite the fact that all these films stirred political controversy and debate across India, Bhati asserts that there was “no political motive” behind the screening of 72 Hoorain.

In the past, the JNU administration has been accused of stopping screenings on the campus. In January 2023, a power outage on campus prevented the screening of the controversial BBC documentary India: The Modi Question and students alleged that they were pelted with stones. The students said that power was deliberately turned off, a claim the university administration denied.

N Sai Balaji, the state president of the Left-wing student organisation All India Students Association (AISA) and a former JNUSU president says that forums like the Manch are run by the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), which is backed by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and operates via these study circles to avoid accountability.

“It is ironic that they propagate hate and screen such movies and yet hide behind the duplicity of forums that become active at the time of such events. When we screened the BBC documentary, we owned up to it, something the frontal organisations by ABVP would never do. Why is a study circle screening such movies? When you choose to study, you wouldn’t show such movies,” he adds.

The Vivekananda Vichar Manch, on its part, chooses to focus on the larger picture. Bhati says that the forum discusses both national and international politics. The JNU administration, she says, stifles no voices—Left or Right.

“There should not be an issue. We are neither Left nor Right. We are associated with the Bharatiya ideology, and that is what we talk about. We talk about ground issues, and, going ahead, we will host more such events. Next Sunday, we are hosting a debate on the tribals of India. We also discuss relevant issues. Movies tend to lead to greater limelight,” Bhati adds.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)