New Delhi: A book on the gardens of Delhi can’t just remain restricted to a tome on the city’s green spaces. It is bound to generate a conversation on the ebb and flow of history, the Mughal era, decolonisation and climate change.

It is, after all, 2024, everything is political and contested. Even memory.

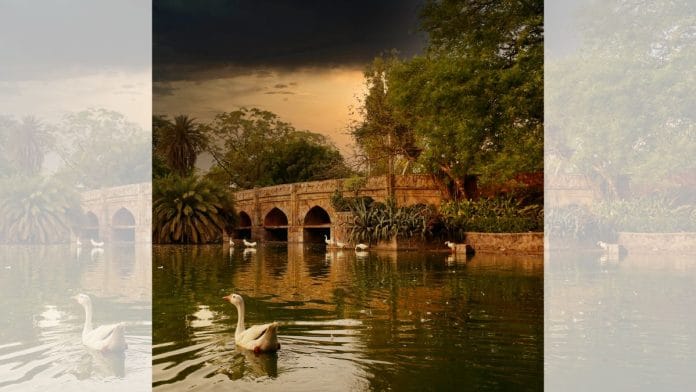

The launch of Gardens of Delhi by historian Swapna Liddle, amateur naturalist Madhulika Liddle and photographer Prabhas Roy last week couldn’t have come at a better time as the capital battled an extreme heat wave.

The book isn’t just a listicle of places to visit for the Instagram Reel era. It weaves history and horticulture seamlessly to create an intimate portrait of Delhi through its changes.

Conversation about writing the book began when the two authors saw Roy’s moving photographs of the gardens. A list was drawn up. Changes were made. Some were dropped after research, others were added. Historian Liddle poured through a number of travellers’ accounts, chronicles of how the gardens were founded and the documents at the Delhi archives. Naturalist Liddle visited the gardens during different seasons to see how they change—the research mostly involved walking, she quipped.

Their research for the book threw up some precious discoveries too. They found a ‘tree of owls’ in a nook of Nehru Park; Lodhi Garden has a really old mango tree that is one of Delhi’s 16 heritage trees; a painted plaster at the Roshanara Bagh of Sita Ashoka trees; Deer Park had no garden design or history; the Mehrauli Archaeological Park wasn’t from the Delhi Sultanate period but was laid out as a garden only much later in the 18th and the 19th century; the Buddha Jayanti Park has a cutting from the original Bodhi tree; Shalimar Bagh was where Aurangzeb wore his crown, Qudsia Bagh was where the British kept their troops: and that people wanted to be buried near Sufi saints, so the tombs from Nizamuddin Dargah to Sunder Nursery to Humayun’s Tomb to the Lodhi Garden was just a large necropolis.

Also read: Mughals are synonymous with gardens in India. Even British adopted the style

Aspirational gardens

The go-to Bible on the subject until now has been Pradip Krishen’s Trees of Delhi: A Field Guide. But that was nearly two decades ago. A lot has changed since.

The new book by the Liddle sisters comes as a much-needed breather—Delhi gets a bad rap every year as India’s toxic air-polluting capital. So it would be counter-intuitive to many that at over 23 per cent tree cover, Delhi has the largest green cover among the metropolitan cities in India. And it has more than 18,000 public parks and gardens.

“Delhi is often remarked on for having an unusual amount of green cover for such a large urban agglomeration. This is, however, a relatively new phenomenon,” the book said at the outset. “Delhi’s climate is not naturally conducive to lush vegetation.”

At the book launch, there was excitement among a panel of speakers about some of the city’s neighbourhoods categorised as gardens. Several residential colonies have the ‘bagh’ or garden suffix to their names—Shalimar Bagh, Punjabi Bagh, Jor Bagh, Moti Bagh, Karol Bagh, Dilshad Garden and Maharani Bagh.

But not all these were historically gardens, said Swapna Liddle. Jor Bagh and Karol Bagh were gardens, Shalimar Bagh is one of the few places where a lot of fruit trees can still be found, Maharani Bagh offered no evidence that it is a garden, neither does Dilshad Garden or Punjabi Bagh. The Mughal-era Roshanara Bagh became a cricket ground and is now a club. Sunder Nursery is rich in its variety of trees and is a wonder of horticulture, but historically it wasn’t a garden.

“From the time New Delhi was built, there was this idea of Delhi as a garden city,” Swapna Liddle said. “That has led to a lot of aspirational naming of residential colonies. These colonies see themselves as green.”

Also read: Centuries-old history on the line in Delhi—Sunehri Bagh to Shahi Masjid fear DDA bulldozers

Changing idea of gardens

“If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need,” said the ancient Roman philosopher Cicero.

The authors bemoaned what has become of the Hayat Bakhsh Garden (or the life-bestowing garden) inside the Red Fort. Built by the Mughal king Shah Jahan, the garden was rich with pavilions, water channels and walled enclosures.

“In its heyday, there was a dense canopy of trees that light could not penetrate at noon,” co-author Madhulika Liddle said. “Now there is just a row of Ashoka trees down on the sides. You don’t think of it as a garden. There is really nothing there now which evokes our notion of what a garden should be. But it is very emphatically a garden.”

Reading the book can bring joy but also a sense of profound loss. And that sense of loss was palpable among the middle and old-age audience who had assembled at the book discussion.

One woman framed her question as a lament.

“I feel such a sense of loss. The kind of trees they have replaced. Jungle jalebis, jamun. I lament the loss of old trees,” she said.

The authors, however, were quick to assuage such comments about loss with a reality check. Their message was simple. Change is constant.

“Every regime brings in their ideas of what their gardens should look like. It changes. What the Mughals planted was not what the British wanted to plant. Where the Mughals had a canopy of trees, the British built lawns,” said Madhulika Liddle. “Our ideas of what comprises horticultural, botanical beauty have changed over time.”

When New Delhi was planned, the British officers drew up a list of 13 tree species to be planted along the avenues. A lot of trees that are popularly associated with Delhi today—champa, gulmohar, amaltas—were not even on that list. There are trees that have come in now that didn’t feature in Krishen’s comprehensive book in 2006.

Interestingly, some 19th-century drawings and photos showed large areas of south Delhi as bare treeless vistas, Swapna Liddle said. The trees came later, when the houses were built.

Also read: The Mughals are overdone in historical fiction. Time to focus on Delhi Sultans

Lack of ecological awareness

Krishen, author of Trees of Delhi and filmmaker, called the new book a game changer, one that would serve as a good beginning to look at gardens critically in the context of water scarcity and climate change.

He narrated an anecdote to demonstrate the lack of ecological awareness among the capital’s horticulture officials.

In the 1950s, a team from the Central Public Works Department designed the Buddha Jayanti Park and imagined it to be a version of the Japanese zen Buddhist gardens.

“What did CPWD’s horticulture department do? They simply took trees and shrubs from the Lodhi Garden and brought them to the Buddha Jayanti Park,” Krishen recounted. “Lodhi Garden was perfect, they thought. Why not simply replicate it? And then they began to wonder why these trees didn’t do very well there. Nobody told them the difference between the Lodhi Garden situated in the old floodplain of Yamuna and the rocky ridge of the Buddha Jayanti Park.”

This issue is still not resolved. Massive amounts of water are still being used in trying to keep it alive. It’s a lost cause, he said.

He also expressed his misgivings about how the public fascination with manicured green lawns is problematic because they are massive water guzzlers.

“We need to decolonise the ways in which we think about our gardens,” Krishen said. “We need to completely throw away all our ideas about what to plant, ideas that we have inherited from the colonial era.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)