New Delhi: India is losing its footing as a “conservation leader”. Conservationist and author Prerna Singh Bindra holds the explosion of heavy infrastructure like highways, power plants, industries and townships responsible for this.

“The country’s conservation era from 1972 onwards was a lesson to the world to preserve wildlife,” she said at a talk titled, ‘India’s Wildlife Crisis and Why It Matters’ on 10 May at New Delhi’s India International Centre (IIC). A strong legal and policy framework was put in place with the Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972, The Forest (Conservation) Act 1980, and Project Tiger (1973). These laws along with initiatives like the establishment of the Wildlife Institute of India in 1982 helped protect wildlife on the brink of extinction.

But Bindra fears that this framework is under threat as well. “We are on this path of relentless, unplanned development which does not factor in ecological concerns,” she added.

In a career spanning two decades, Bindra has served as a member of India’s National Board for Wildlife and is currently on the board of the Hathi Sathi Foundation which works toward enabling safe shared spaces for people and elephants in northeast India. She has authored several books including The Vanishing: India’s Wildlife Crisis and co-edited Wild Treasures: Reflections on Natural World Heritage Sites in Asia.

According to Bindra, environmental and wildlife concerns are often neglected, if not entirely absent, from the national agenda. They are rarely a talking point in election campaigns. To prove it, she challenged the audience to identify just one environmental or wildlife-related concern that voters have given due consideration in the ongoing Lok Sabha election.

“Year after year, our children grapple with severe respiratory problems as a consequence of pollution. But do we see this reflected in voter priorities? Do political parties or leaders incorporate it into their agendas?” she asked a silent audience.

She accused successive governments of turning a blind eye to nature’s call for help in pursuit of a higher GDP.

“They [forests and wildlife] aren’t really a vote bank after all,” Bindra said.

According to her, merely five per cent of India’s land is safeguarded through national parks and biodiversity reserves, a figure that falls significantly short of the global average of 15 per cent. Even India’s neighbouring countries, Bhutan (nearly 50 per cent) and Nepal (20 per cent), boast higher proportions of protected areas, she said.

Bindra, who is currently doing her PhD at the University of Cambridge in the UK, spoke about her time at India’s National Board for Wildlife from 2010 to 2013. “The first takeaway was realising how unprotected protected areas truly are,” she said. However, Bindra emphasised that by adhering to the NBWL’s mandate as a member to conserve wildlife, one has significant power to effect change.

But before she launched her PowerPoint presentation she wanted the audience to breathe.

“Let’s begin by taking two deep breaths,” she said, urging the around 50 people in the hall to inhale. “The first breath we owe to the forest, and the second to the ocean.”

Also read: Tourist rush into a sleepy Tamil Nadu town causing wildlife roadkill. 2 ecologists helping

Laws & conflict

Bindra fears that India’s laws will not hold against the country’s march towards unplanned development. Laws which once were the backbone of India’s forests and wildlife are steadily being weakened and diluted, she argued.

But there’s another threat to India’s flora and fauna—large-scale construction within natural habitats, which has resulted in the rise of human-animal conflict.

The construction of a dam, as part of the Ken-Betwa River linking project, in the heart of Panna Tiger Reserve is one of the many examples. “It lacked a comprehensive, social environmental impact assessment and against all the scientific advice, the project was given a green flag by the NBWL,” she said.

Every few days, we come across headlines like ‘Man killed in leopard attack’, ‘Herd of elephants destroys crops’, ‘Angry mob throws flaming tarball on baby elephant’ and so on—“It breaks my heart. Both the man and the wild are victims in such situations,” she said.

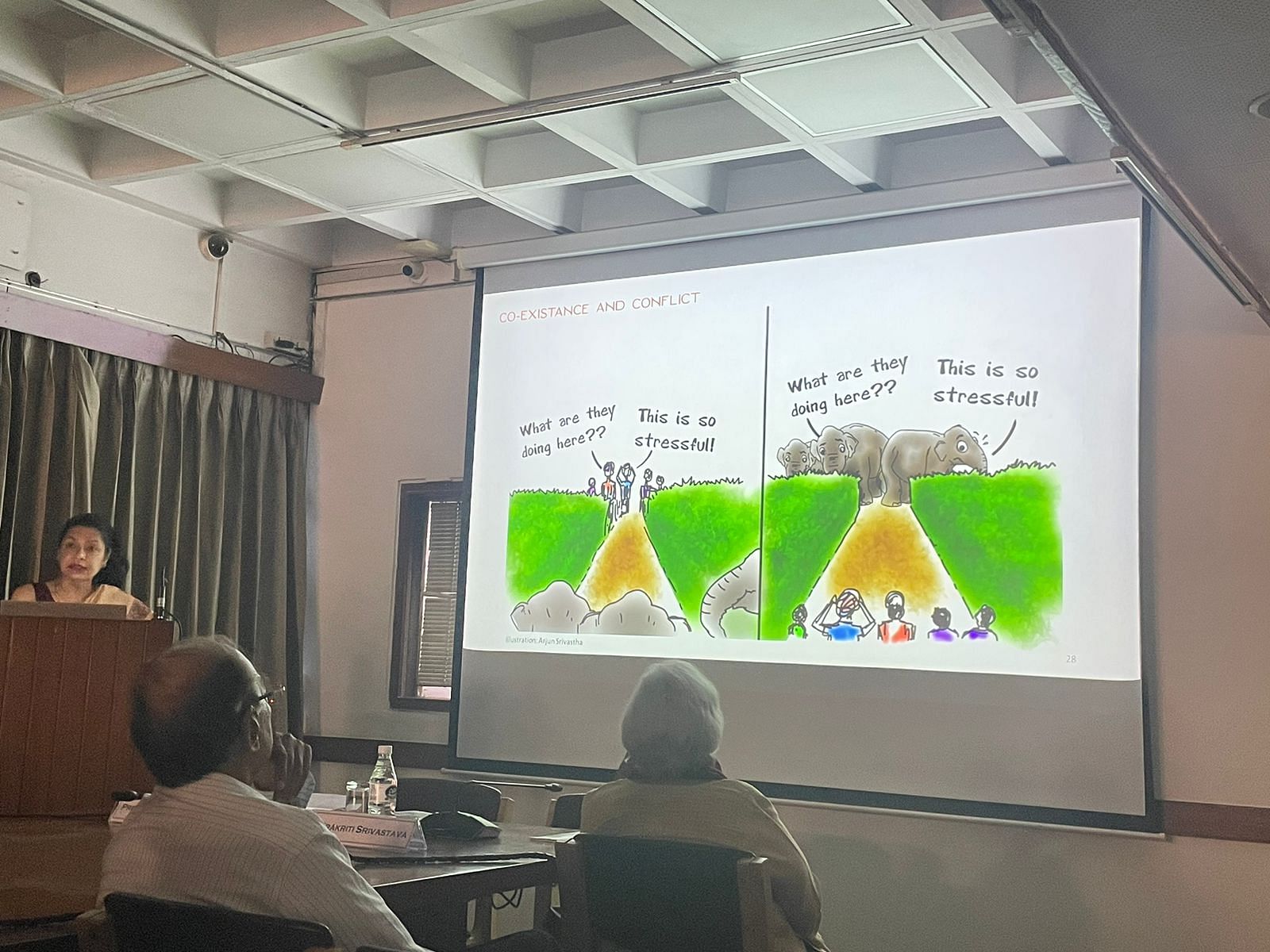

Her statements were accompanied by animated illustrations and doodles of such conflicts. One such illustration, of a surprise encounter between a human and an elephant in their natural habitat, elicited laughter.

“So true,” murmured a group of attendees.

Also read: Indian govt still doesn’t know what a ‘forest’ is. FCA amendment takes us back to British era

Where does India stand?

But even the wittiest of cartoons and drawings couldn’t provide much relief from the grim subject that is the future of India’s forests and wildlife.

Once a ‘conservation leader’, India is visibly going off track, declared Bindra before presenting one data point after another. India is at the bottom of the 180 countries in the 2022 Environment Performance Index, evaluated on various indices. The hundred most polluted cities in the world are in Asia, and 83 of them are in India, according to a report by IQAir. They exceeded the World Health Organization’s air quality guidelines by more than 10 times.

The problem doesn’t end here. India ranked second, after Brazil, in the race for the highest deforestation rate. We lost 668,400 hectares of forest cover in the last 30 years.

To top it off, she added, over 50 per cent of India’s population depends on forest and natural ecosystems for survival, sustenance and livelihood.

“Deforestation and erratic weather hit the marginalised the hardest,” she said. But, there is still hope. “Till the last tiger remains, there is always hope.”

Also read: Jungle life is wilder than you know. Ex-IFS officer’s new book reveals politics of forest

Never say never

To illustrate her optimism, she shared a video depicting how an entire village, and some forest officers, in one Maharashtra district, united to rescue a leopard that had fallen into a well. As it emerged from the well and bounded back to its habitat, the villagers— as well as the audience sitting in the room—were relieved.

Reports of people going out of their way to help a wild animal in distress are a much-needed dose of optimism. Bindra emphasised the need to integrate wildlife and environmental concerns into mainstream discourse. She urges people to weigh the environmental costs of development and question who truly benefits from it.

“It is essential to factor ecology in every decision. Otherwise, we risk transforming India into a concrete jungle and losing its natural heritage, forever,” she said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)