New Delhi: Not a single image in ‘Self-Discovery via Re-discovering India’, an exhibition of seminal photographs by India’s greats, carries a caption. This was a deliberate move by curator Neville Tuli—it allows the viewer to construct their own photographic narrative. To see the image for what it is, or for what they believe it is.

“This crutch [write-ups] has stopped people from looking at images. It’s not the way to view images. It’s visual illiteracy that’s so dominant today,” said the archivist and curator, also the founder of the Tuli Research Centre for India Studies. “Visuals should be at the centre—used as a source of knowledge.”

According to Tuli, India is yet to locate its visual language. And the exhibition, the third of a series, is one such attempt. By opening up his trove of rare photos—many of which document seismic churns in India’s history, each of them a coming-of-age moment. The exhibition, held at Delhi’s India Habitat Centre, lays bare a slew of narratives for the viewer to stitch together.

Collecting, archiving, and documenting has been Tuli’s life’s work. And bit by bit, he’s sharing it with the world. This includes Henri Cartier-Bresson’s iconic photos of Gandhi, and of Nehru announcing his assassination. There are also photos of Satyajit Ray shooting, and of Dadasaheb Phalke clicking his own photo—India’s first selfie, according to Tuli.

These are punctuated by essays on each photographer. Such is the extent of the void when it comes to Indian photography, that for RR Bharadwaj—known for his photos of the countryside—no such documentation existed.

These photos barely scratch the surface of Tuli’s archive—which contains 26,000 historic photographs. What the exhibition does instead is give viewers a taste of photography as a discipline, as a knowledge base.

“I’m preparing the ground for that sharing. That’s a process that has to be true to history,” Tuli said. “The way you capture the essence of a category in one image.”

Also read: AI Mona Lisa to touchscreen Last Supper, Da Vinci goes hi-tech. Some call it ‘dumbed down’

India’s tryst with documentation

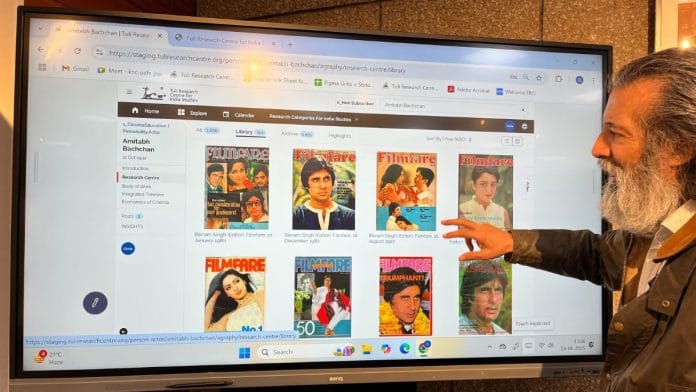

Tuli’s ultimate dissemination, the unearthing of thousands of photographs, will be taking place soon. The Tuli Research Centre for India Studies is in the process of building a search engine through which images and information will be available at everyone’s fingertips. It will be free, have a user-friendly interface, and bring a host of cultural figures under the same digital umbrella.

“There’s a deep-seated ignorance that we’ve absorbed and accepted. It’s a system that’s continuing,” said Tuli, referring to modes of education that have trickled down over decades. “The act of self-discovery is the essence of wisdom.”

What cultural education boils down to is access. Tuli always wondered why the Sotheby’s and Christie’s of the world didn’t grow into great universities—given the staggering wealth of artefacts and sources of knowledge at their disposal.

Tuli himself is an art collector, having founded Osian’s Connoisseurs of Art. He’s thus brimming with tidbits that can morph into an art history lecture.

“Jamini Roy took folk art to the Western world. And he used a picture of Jesus,” he said. “Imagine the power and the empathy that the Indian creative mind had.”

Students from Delhi’s Bal Bharati School also attended the exhibition, and were given a walk-through by Tuli. He asked them to think of a single image that had the greatest impact on them. All of them chose a different one. Such is the medley of minds, the diversity on display in schools—potential that he wants to tap into.

‘Self-Discovery via Re-discovering India’ is a country’s tryst with documentation. There are several coming-of-age moments, including the opening of the Metro Cinema in Mumbai and factories being built as India began to industrialise.

“I describe India as a mixed pickle. You put the ingredients in the sun… We see how each juice interacts with the other. One shrivels, one enlarges,” he said. “That’s the nature of interrelation.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)