New Delhi: There’s a gap of a little over 20 years between the death of Isa Khan and that of Humayun. But within that short span of time—the second Mughal emperor orchestrated an architectural coup. He amped up the scale and made sure stylistics were different. Humayun’s tomb was a “benchmark”, a paragon of architecture, till the 17th century—when it was replaced by Shah Jahan’s Taj Mahal.

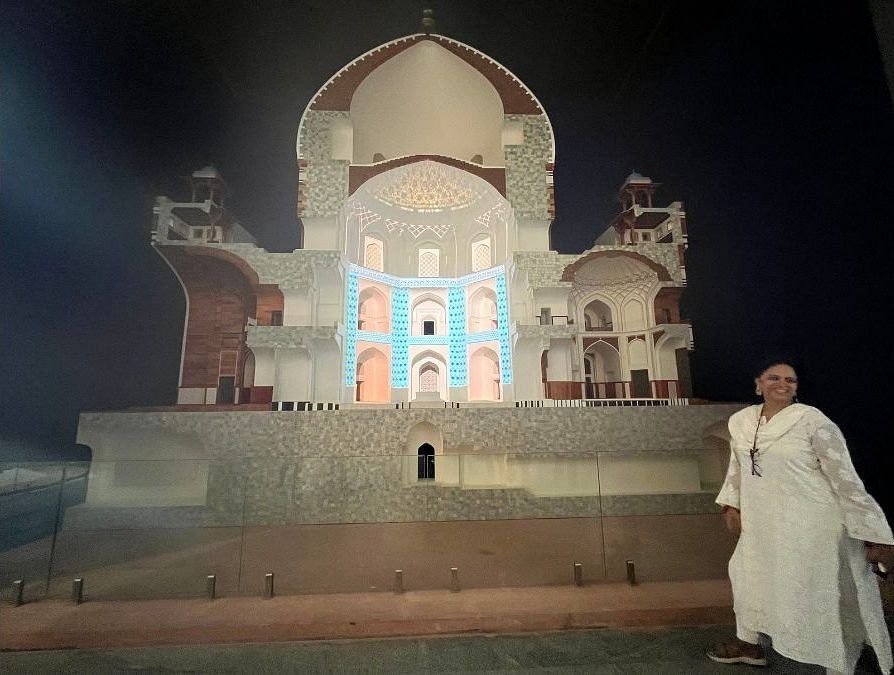

Part of UNESCO’s project to build museums on World Heritage Sites, the Humayun World Heritage Site Museum bridges a knowledge gap. Sandwiched between Babur and Akbar, Humayun has been given the short end of the stick when it comes to popular representation. But through a potpourri of artefacts, architectural tidbits, historical documents, paintings and projection mapping—not just Humayun, but the entire area of Nizamuddin has been given a fresh rendering.

“This is the entrance zone of the world heritage site and it’s generally a recommendation that a site museum is along the entrance,” said Ratish Nanda, CEO, Agha Khan Trust for Culture. “It’s particularly important for Humayun’s tomb because there’s 500 years of history. And we’ve distilled that into 150-word blurbs.”

A collaborative effort between the Archaeological Survey of India and the National Museum, from which rare originals have been procured, like the manuscript of the Ain-i-Akbari, has resulted in the unveiling of a number of lesser-known facts about Humayun, the empire, and Nizamuddin.

“We have to look at how an urban park needs to be managed. The events that need to happen, and how a space like this needs to be maintained,” said Archana Saad Akhtar, programme director at the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, at a walkthrough for the museum, which will be opened to the public on 1 August.

Akhtar described the emperor as the most “cosmopolitan” of Mughal emperors. As for his travels—he ventured out more than the much-lauded explorer Marco Polo. They weren’t easy either. He had a helmet that once doubled up as a cooking utensil for horse meat.

“Humayun travelled 36,000 kilometres throughout his life. And he brought back influences from the places he visited,” Akhtar said. “He met with miniature painters in Iran, got them to India, and laid the foundation of Mughal miniature paintings.”

The museum functions as a bit of a disruptor. One of the most common perceptions of Humayun is that he was an incompetent military ruler, by and large because he was defeated by Sher Shah Suri. But a section of the museum—peppered with artefacts, such as chain-link helmet replica—is dedicated to his military endeavours. Humayun played a “significant role” in Babur’s military campaigns, and did his bit to stretch the empire—which he extended to Bengal in the east, and Gujarat in the west.

Also read: My wheelchair visit to Humayun Tomb stopped at Isa Khan. Sympathy can’t replace rights

A narrative of Humayun

The museum is a grey-scaled, airy space that has been built underground in order to not interfere with “view corridors” facing the monuments. Its bare canvas has permitted the entry of a slew of objects—some of which have literally been taken from the tomb and deposited. There’s a floor-to-ceiling red sandstone jalli that has been transported from the tomb, artfully broken. The original finial is caged behind a sheet of glass, but a massive

metal replica—which provides a sense of scale, has been given prime real estate. Since finials are effectively crowns for buildings, they aren’t usually seen, said Akhtar.

Apart from objects that permit viewers to stitch together a narrative of Humayun, his architectural contributions are also given great play. Other than the tomb, of which there’s also an original floor plan, a number of his buildings once dotted the cityscape of Delhi. Many continue to do so.

“Humayun’s architecture can be divided into three—architecture that survives, that which doesn’t, and ephemeral architecture,” said Akhtar.

What doesn’t survive is the Mystic Palace, which has been recreated through a film that plays in one section of the gallery. A supposed marvel, it is here that the wedding of Humayun’s brother was organised. Located in Agra, It was pieced together by scrutinising historical records.

In his style, according to Akhtar, Humayun “tried to synthesise Indian traditions and Timurid traditions.” His chhatris (dome-shaped pavilions) are evidence of this.

But even when it comes to monuments that appear to have been maintained, there are challenges. Akthar’s first memory of Humayun’s Tomb is of canopies covered in cement plaster. Beneath the canopies, was tile work.

“Traces of tile work were seen on the basis of which ones we could conserve. We tracked the craftsmanship to Uzbekistan, after which craftspeople stayed with us for ten months,” she said. “And then we could replicate the work.”

The exhibit on ephemera is still to be displayed, but Akthar divulged one example—the boat palace.

Also read: The Mughals are overdone in historical fiction. Time to focus on Delhi Sultans

‘Dormitory of Mughals’

The museum is seated between Humayun’s Tomb and Sunder Nursery, which was also refashioned into a tourist-cum-cultural hotspot. The curation of the museum plays with its location—the historically dynamic Nizamuddin area.

“We had to be careful because there are several important national monuments surrounding the museum on all three sides,” said Nanda. Sabz Burj is towards the west of the museum, Isa Khan’s tomb is in the east, and there’s Sunder Burj in Sundar Nursery.

A timeline on one wall reveals that every single Mughal ruler, and several aspirants, had links to Nizamuddin. Right after he defeated the Lodhi sultans, Babur visited the grave of Nizamuddin Auliya on pilgrimage. Dara Shikoh, whose head was gifted on a platter to Shah Jahan by Aurangzeb, is buried in Humayun’s mausoleum. Jahanara Begum is buried in Nizamuddin Basti.

Akhtar described the complex as “a dormitory of Mughals”. There were about a hundred monuments in Nizamuddin, and approximately sixty remain. Right outside Sunder Nursery, on the busy Mathura Road roundabout, is Sabz Burj, also restored by the Aga Khan Trust. It is the mausoleum of Humayun’s mother.

Beyond Nizamuddin, close to the Yamuna, once lay a pavilion built by Humayun. By the time Shah Jahan took the reins, among other things, tile work had evolved. His grandfather’s simple tiles had been replaced by more ornate tiles. According to Akhtar, in the 1950s, the pavilion was converted into a temple. And the Mughal-era tiles were thrown out.

They were collected by a Persian scholar and finally made their way to the Aga Khan trust through an anonymous donation. The original tiles are on display at the new museum, colourful and intricately detailed.

The museum then gives way to Humayun’s obsession with astronomy and astrology. He wore a different colour each day, as chosen by the stars. Black was reserved for Saturday. That’s when he met “literary and religious persons”. His eclectic wardrobe has been brought alive through a series of six metallic sculptures—each colour is vibrant against the dull gold.

There are peculiarities, marvels, and cold hard facts that have flown under the radar. But now, it’s a wrong that’s been corrected. “He had a great father and a great son. So we had to make a museum for him,” said Akhtar, only half-jokingly.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)