New Delhi: Biryani, kababs, and if you stretch your imagination nihari and haleem—but always meat—are what come to mind when thinking about ‘Muslim’ food. This was how Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, co-editor of Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia, thought about the category too. But when researching for the book, she discovered it was so much more—dal, khichdi, sarson ka saag, kadhi.

Her chapter in the book, You Are What You Eat, is accompanied by a recipe for soybean biryani. “In memory of Junaid Khan” reads the title. It was the favourite dish of the 15-year-old boy who was lynched in 2017 over a fight onboard a train. He was reportedly called a “beef-eater” during the attack. Like the rest of the book, the chapter by Lambert-Hurley doesn’t shy away from the politicised nature of food in India.

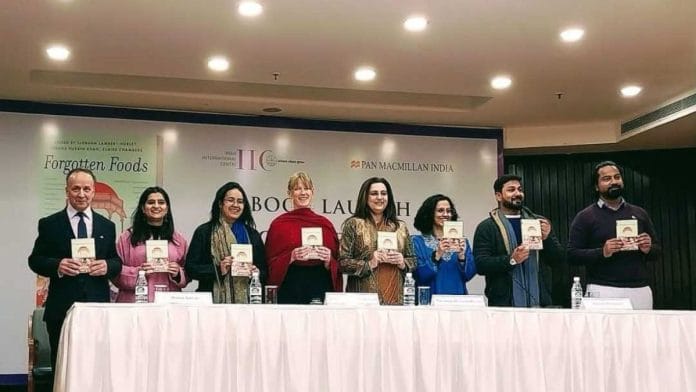

“It’s important to draw positive attention to Muslim communities and their food. And by celebrating these cultures we can bring everyone to the table. Hopefully, then the table becomes a place for discussion and sharing,” said Lambert-Hurley, a professor of global history at the University of Sheffield, at the launch of the book at India International Centre, New Delhi on 8 January.

The insights from the book by Lambert-Hurley, co-editor Tarana Husain Khan, and seven of the 24 contributors and the food that was promised after the session—Bihar kebabs, Rampuri adrak halwa—made sure every seat at the IIC auditorium was occupied.

Fullbright-Nehru student researchers, Abhiyudh Rajput and Frances W, came for the free food and didn’t expect to be as drawn to the book as they were by the end of the event.

Discussions about labour and the gendered aspect of food “that we eat very quickly” caught Frances’ attention. “It makes me want to eat slower,” said Rajput.

Also read: There’s one sector Gurugram isn’t competing in with Noida—middle-class homes

Preserving food memories, cultures

The book is an unofficial sequel to Claire Chambers’ Desi Delicacies: Food Writing from Muslim South Asia, which was released in 2020. Chambers was a co-editor for Forgotten Foods as well.

“It was important to move beyond elite food cultures [mentioned in Desi Delicacies] and look at the labour that goes behind the production of elite foods. And food cultures that are not born out of royalty,” said Lambert-Hurley.

Mothers and grandmothers who took charge of home cooking, street vendors, and khansamas are keepers of knowledge passed down through generations. “Collecting their memories and culinary traditions in this book was an important goal,” said Khan.

The book is a combination of academic and creative writing, a purposeful choice informed by the variety of people whom the editors tapped to bring it to life. “We wanted to bring together academics of all kinds—historians, sociologists, plant historians— and those who are interested in food in a much more public way—writers, heritage practitioners, chefs,” said Lambert-Hurley.

The ideas born in the process went beyond just the pages of the book. Khan and Lambert-Hurley found and revived the forgotten Tilak Chandan variety of rice once abundant in Khan’s native Rampur—immortalised in a chapter in the book, The Quest for Tilak Chandan.

Khan made an important discovery when the two co-editors experimented with audiences in New Delhi, Sheffield and Rampur. They served two portions of the Rampuri urad dal khichri—one made with the traditional Tilak Chandan and the other with hybrid basmati.

Those in New Delhi and Sheffield were split between the two. “But the minute we served it in Rampur, they exclaimed ‘Oh this is Tilak Chandan where do you get it now’,” said Khan.

It brought the realisation that dying food practices were akin to a cultural loss. “We grew up with it, but it disappeared sometime in the early 90s,” said Khan. The book underlined that the “over 2 lakh varieties of rice” that have been lost aren’t mere numbers but hold deep emotional and cultural significance.

This core idea is what makes the book significant. “Our memories are based on food. We don’t know how many of these small communities will fare over the next several years. So, all we can do is put down what they feel about food and how they express their identity through food,” said Khan.

Also read: Could Vadnagar rewrite history? 3,000-yr-old Gujarat town holds clues to India’s ‘dark age’

Forgotten, not lost

The showcase of Muslim food was not a simple celebration, though, and it appealed to archivist and oral historian Farah Yameen. Her chapter in the book, On Bakr Eid, uses the festival to draw attention to caste in the Muslim community.

Yameen writes about how who eats what part of the sacrificial goat is determined by caste—the offals and “smellier” parts of the animal were reserved for the lower caste folk employed in the homes of the upper caste.

“It’s very difficult to bring up caste [among Muslims] because we generally talk about how we are egalitarian. But no religion is sealed off from cultural influences and caste plays an important role,” Yameen told ThePrint.

She recalled that when her family members and others read her chapter in the book, they said, “It’s such a good piece about charity.”

“But this is absolutely not about charity, it’s about how our charity is self-serving,” she said.

Hindu influence on Muslim culture was one of the themes that ran through the book. It was something that surprised Saumya Gupta, associate professor of history at Janki Devi Memorial College, University of Delhi, who was a contributor to the book.

She researched Hindi cookbooks from the 1920s and 1930s and was unsure what she could bring to the book. However, when she delved into the histories, she saw cookbooks where the Hindu-Muslim cultures collided. “I had to reimagine a world where the divisions we have today weren’t as fundamental. These were shared spaces,” she said.

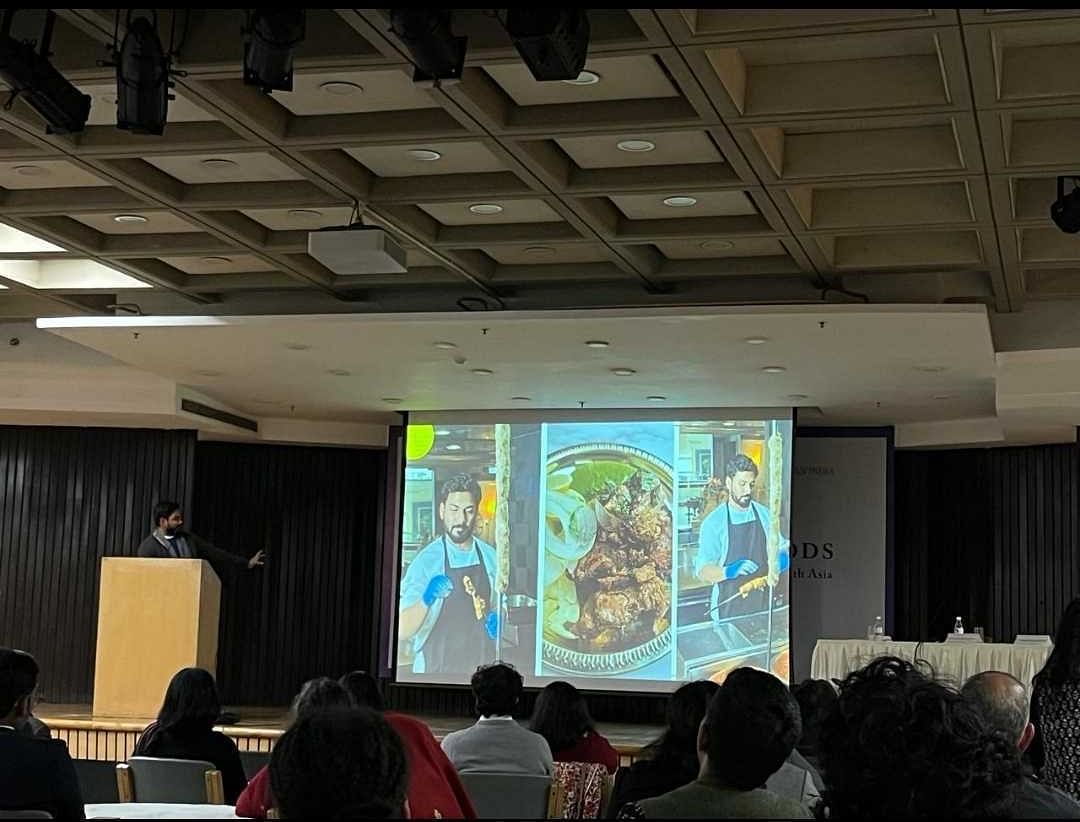

Masterchef India 2016 finalist and food writer Sadaf Hussain’s presentation on Bihari Kabab was the last one before the audience could leave the hall to eat the delights. The smell of the kabab wafting through the hall made stomachs grumble but Hussain’s humorous history lesson made sure waiting was an easy task.

He began with a nod to the title of the book. “I hate the word lost. What may be lost to you is being cooked in someone’s kitchen. The Bihari kabab is not lost, it has only been forgotten,” he said.

Curiously, the kabab is more popular in Pakistan than its namesake city, Hussain added. He took the audience through what sets the dish apart—its ingredients, such as poppy seeds, sattu, dried coconut, and papaya juice; the cut, thinly sliced pieces of red meat; and the manner of cooking, on a sigdi (iron stove).

The presentation was accompanied by AI-generated images of kababs but none of them were Bihari kabab. Hussain tried, he said, to get the right image. “If I go a little further it’ll skew a Bihari and say Bihari kabab,” he joked.

While it may not be intentional, the (inaccurate) images were a poignant reminder that there are wide gaps in our digital libraries. It underlined why memory is a muscle that must be exercised through books like Forgotten Foods.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)