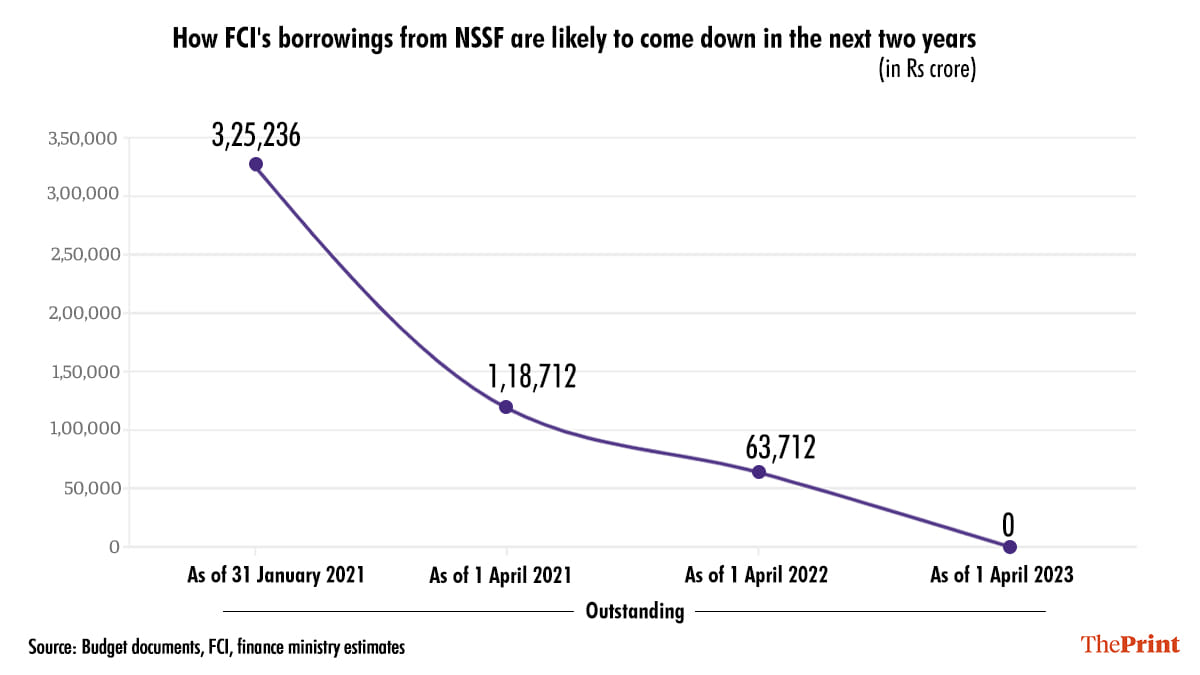

New Delhi: The Food Corporation of India (FCI) is set to clear its outstanding debt of over Rs 3 lakh crore from the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) within the next two years, a key part of Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s budget announcement of a massive clean-up in the way India accounts for its food subsidy.

While this clean-up will bring in the much required transparency in presenting an accurate picture of food subsidy in the budget itself, it will not solve the FCI’s problems as the state-run company continues to battle with a wide gap between its foodgrains acquisition costs and sale prices.

The continuously widening gap is financed by the government by way of food subsidy allocations in the budget, and by providing loans to FCI from the NSSF until recently.

This gap is unlikely to be plugged in the near future.

While the distribution price of foodgrains under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 has remained the same at Rs 2-3/kg, the assured minimum support price (MSP) at which FCI procures wheat and rice from farmers for distribution has skyrocketed.

MSPs are revised every year in line with the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices but the sale prices have remained largely untouched.

FCI is the government agency managing the procurement and distribution of foodgrains. Set up in 1965 under the Food Corporations Act, it is responsible for procurement of foodgrains at MSP, storage and maintenance of adequate buffer stock, and distribution through the public distribution system (PDS).

The agency primarily procures foodgrains like wheat and paddy at MSP, which are raised every year in accordance with inflation in cultivation cost of these crops.

These grains are in turn used to provide 81.35 crore beneficiaries under the NFSA. Under the scheme, people are provided with 5 kg of wheat or rice per month at Rs 2 and Rs 3 per kg, respectively, via the PDS.

“FCI’s operations of procuring large quantities of wheat and rice at MSP and disposing of it both in PDS and OMSS (open market sales scheme) is not sustainable. The economic cost of procurement of foodgrain and their storage, transportation has been rising over the years but the issue price of these foodgrains have been the same under NFSA 2013,” said T. Nanda Kumar, former food and public distribution secretary.

ThePrint reached FCI Chairman and Managing Director Sanjiv Kumar via email on 19 February for a comment but there was no response until the time of publishing this report.

Also read: Why microborrowers in Assam are refusing to repay their loans this poll season

How budget 2021-22 reduced debt on FCI’s books

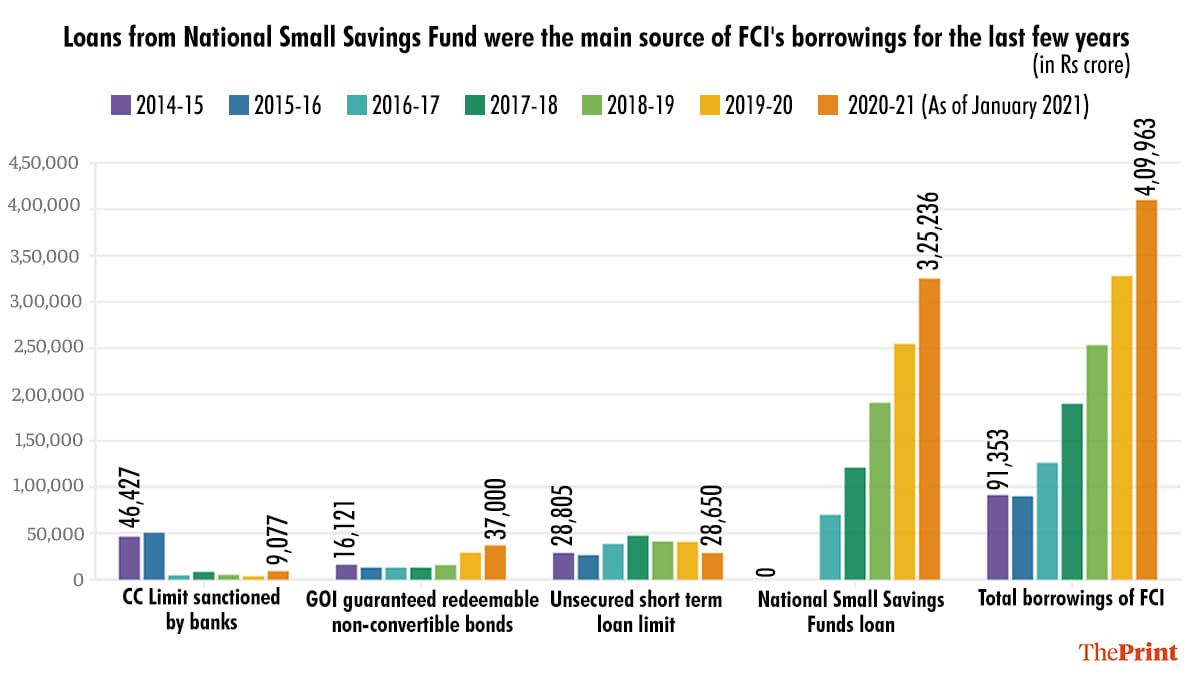

The total debt on FCI’s books, which had exceeded Rs 4 lakh crore as of 31 January, will come down by over half after the government proposed to repay all the loans FCI took from NSSF over the next couple of years.

Of the total debt of more than Rs 4.09 lakh crore as of 31 January on FCI’s books, loans from the NSSF accounted for nearly 80 per cent of the total loans. The remaining amount was accounted for by unsecured short term loans and non-convertible bonds among others.

But according to the roadmap presented in Budget 2021, the FCI’s total borrowings from NSSF will come down to Rs 1.18 lakh crore as of 1 April 2021 and to Rs 63,712 crore as of 1 April 2022 before falling to zero in the 2023-24 fiscal.

However, the food subsidy at the same time will balloon from the initially estimated Rs 1.15 lakh crore to Rs 4.22 lakh crore in 2020-21.

Sector experts point out that while this will help in cleaning up FCI’s books and reduce the interest burden, the larger problem of wide gap between costs incurred and the sale prices remains.

“Due to prepayment of loan taken from NSSF, FCI will save on interest amounting to Rs 16,600 crore and this will also bring down the economic cost of foodgrains held by the FCI. But there are other issues to contend with,” said Siraj Hussain, visiting senior fellow at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER).

“Record quantities of wheat and rice are being procured under open ended MSP operations. But the budget gives no indication of how the government plans to deal with the excess stock of wheat and rice in the central pool,” said Hussain, who is also a former agriculture secretary.

He said the government will have to bring in structural changes in its PDS and procurement policies. “But these need to be planned with a 10-year perspective. Whichever way the farmer agitation ends, the government and the farmers in north-west regions will have to find a way to move to less water consuming crops in kharif,” he said.

“There is little that FCI can do about this situation as it does not formulate the food policy. It is the central government which has to decide agricultural policies suitable for each agro-climatic region,” he added.

Also read: China displaces US to become India’s top trade partner in 2020 despite curbs

FCI’s procurement and distribution costs per kg are rising

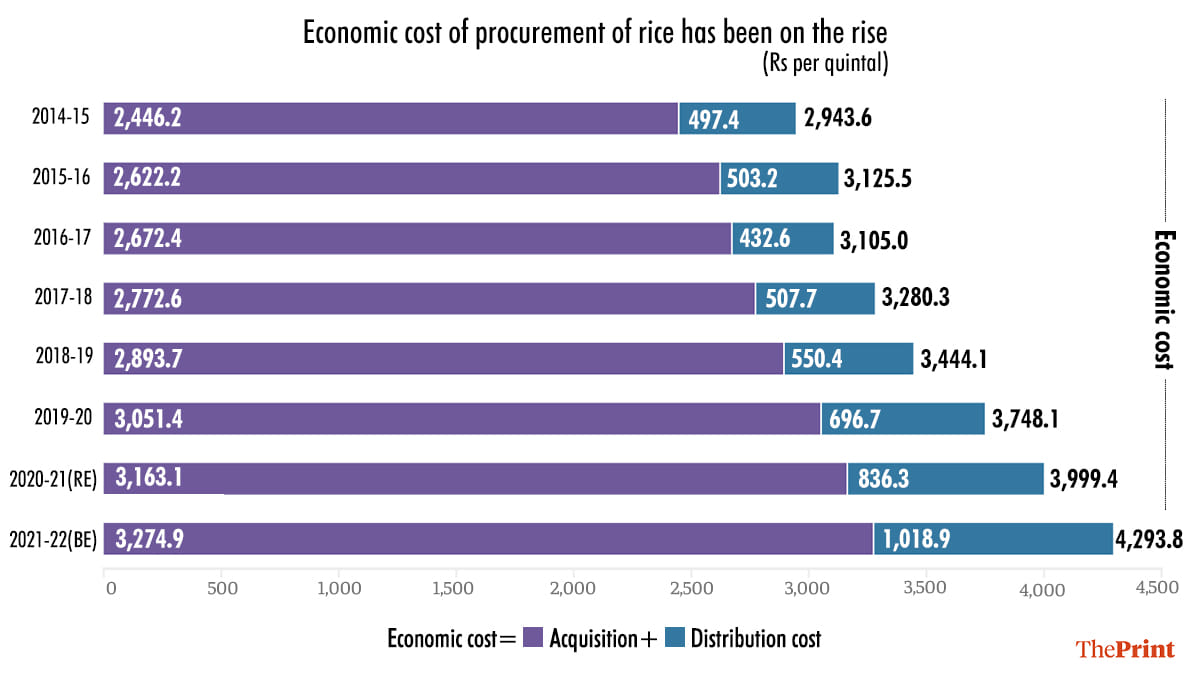

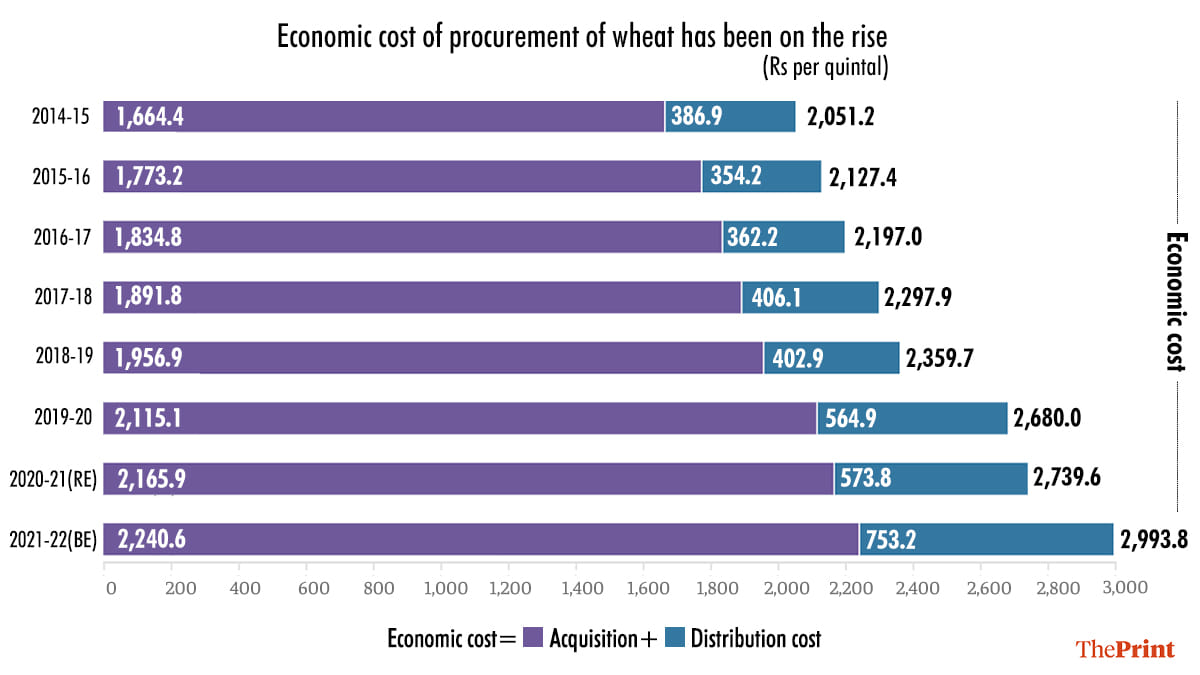

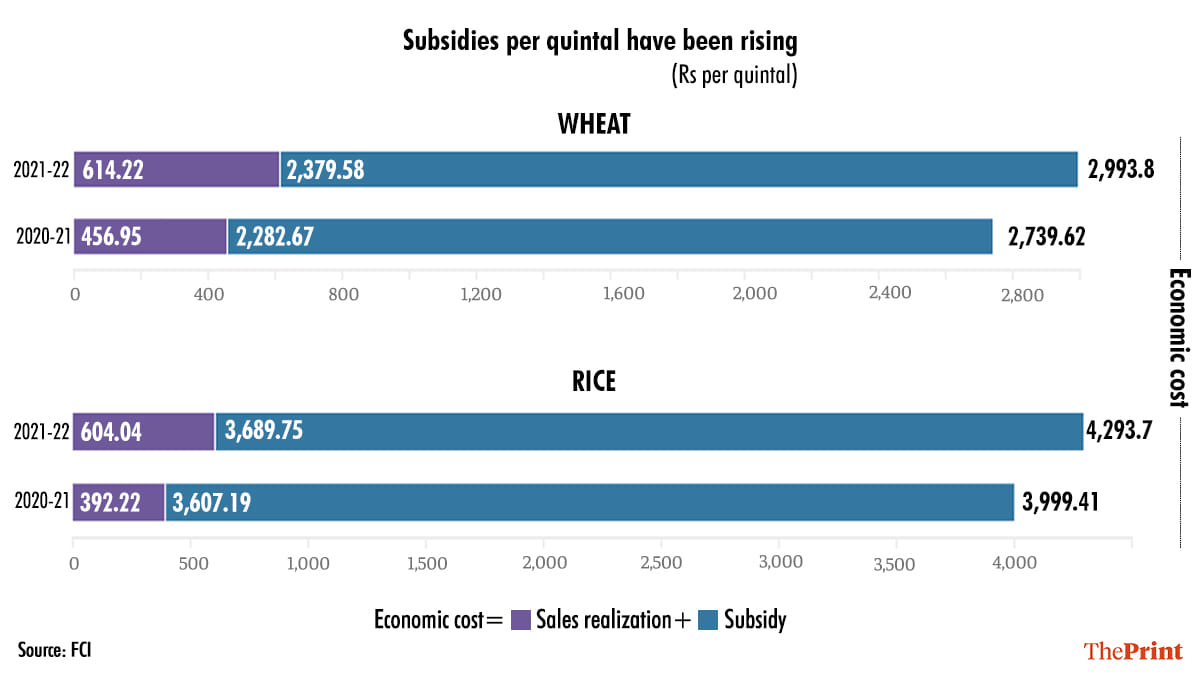

The FCI’s economic cost of operation, which encompasses procurement, transportation, interest, administration, storage and distribution of the procured wheat or rice, is escalating over the years leading posing serious fiscal challenges for the company and the government.

Over the last five years, the economic cost of wheat has increased from Rs 21 per kg in 2016-17 to Rs 30 per kg in 2021-22. Similarly, the cost of rice has risen from Rs 31 per kg to Rs 43 per kg in the corresponding period.

Both rising MSPs and distribution costs have been responsible for this jump.

The MSP of wheat has increased 36 per cent from Rs 14 per kg in 2013-14 to over Rs 19 currently. Similarly, the MSP for rice in 2013-14 was at Rs 13 per kg. It has since shot up 38 per cent to more than Rs 18 per kg.

This has been further aggravated by an increase in costs related to storage, labour and transportation. A mounting stockpile of foodgrains on account of bumper wheat and rice production coupled with assured procurement at guaranteed MSP has increased storage costs over the years.

As of February 2021, FCI had 561.93 lakh metric tonnes (LMT) — 243.62 LMT of rice and 318.31 LMT of wheat — in its stock, much higher than the buffer stock norm of 164.10 LMT (56.10 LMT rice and 108 LMT wheat).

“Even before the implementation of the National Food Security Act, FCI’s operation of procuring, storing and distributing foodgrains incurred large subsidies as the government was distributing foodgrain at lower costs under different schemes,” said Kumar.

“These schemes, however, provided some flexibility to the government as the price and quantity of foodgrains could be changed under the APL (above poverty line) category,” he said, pointing out that this is not the case now. “With MSP at 50 per cent above cost and issue (sale) prices frozen under NFSA, the food subsidy burden will only go up.”

Also read: Indians are cutting down on essentials like onions, wheat to afford fuel hike, survey says