New Delhi: Credit card delinquencies rose significantly in the April-June 2024 period, especially among cards with low credit limits, new data from two credit bureaus shows. This was driven by a sharp increase last year in the number of credit cards disbursed, and low-income customers using them to spend beyond their means, according to banking analysts and economists.

The data shows that, as of June 2024, payments on one-third of credit cards with a limit of up to Rs 25,000 had been defaulted upon for more than 90 days past their due date. This ratio was one-fifth for cards with a limit of Rs 25,000-50,000.

However, economists added that regulators took timely steps over the past year to curb not only growth in credit card issuances but also to curtail avenues for such excessive spending.

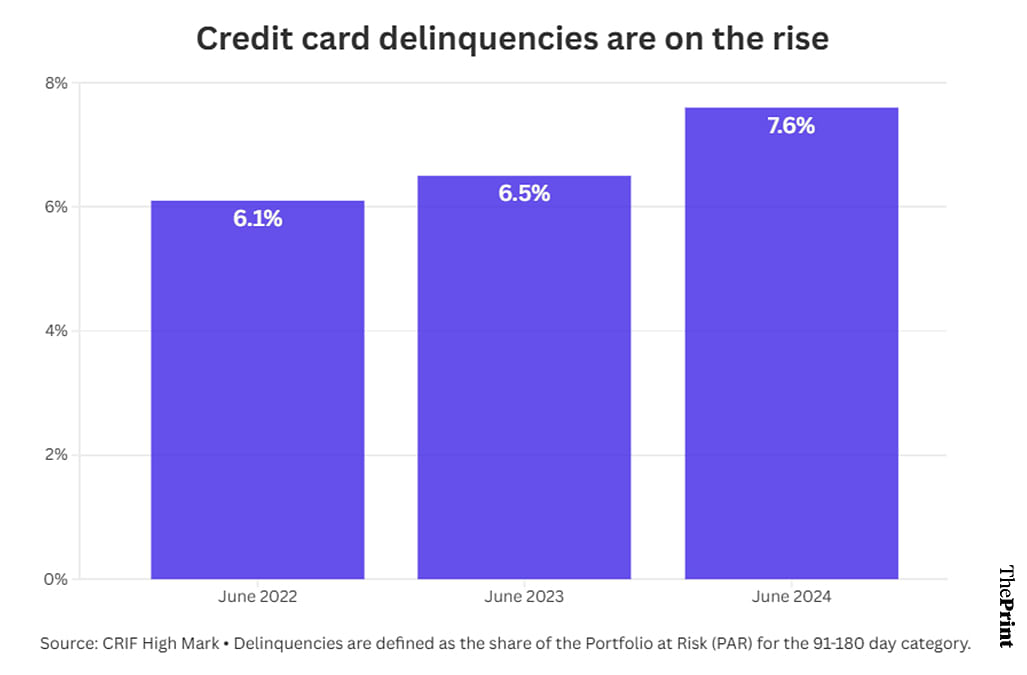

According to data from CRIF High Mark, a prominent credit bureau operating in India, the share of credit card Portfolio at Risk 91-180 (PAR 91-180)—a measure of loans defaulted on for over 90 days and less than 180 days—rose to 7.6 percent in the quarter ended June 2024 from 6.5 percent in the June 2023 quarter and 6.1 percent in the June 2022 quarter.

The proportion of PAR 181-360 rose to 0.9 percent in the June 2024 quarter from 0.7 percent in the same quarter of the previous year.

Data from another credit bureau—TransUnion CIBIL—also showed that the PAR 90+ level stood at 1.8 percent as of June 2024, up from 1.6 percent in the June 2023 quarter.

Also Read: Budget 2025—three reasons your income tax isn’t going down

Stock market boom, F&O party & credit card debt

According to analysts and economists in the financial services industry, there were two main reasons for the increase in credit card defaults.

The first driving force was the sharp increase in the number of credit cards issued last year, and the dilution of scrutiny by card issuers when giving cards to low-income customers.

Intertwined with this, is the second driver: propensity of low-income customers to use credit cards to fund non-essential and conspicuous purchases, which they ordinarily would not have been able to afford.

“What happened is that in 2023, as part of the post-COVID boom, the markets were picking up, and people had this general thought process that the economy is going to pick up and the boom is going to continue,” Vivek Iyer, partner, Grant Thornton Bharat, told ThePrint. “As a result, people started taking aggressive positions in the market, and also started to take a lot of interest in the futures and options segment.”

Iyer added that, when there is an expectation that incomes from other sources, such as capital market exposures, will increase, then people take credit cards and start spending beyond their means, expecting that the cash flows from these other sources will continue.

“Unfortunately, as the year passed by, things did not turn out that way,” he explained.

Adding, “The markets didn’t perform in the way people expected them to and all the credit card spends that had already happened, people were not able to sustainably service them. People prioritised the payments they did want to make, and the easiest thing to defer is the credit card payments.”

India’s tryst with the futures and options (F&O) market has been extensively documented by ThePrint, with reports on the surge in F&O activity in India, how most of the people losing money in this segment are low-income, small-town and young, and how the market regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) eventually took steps to curb the participation of these low-income traders in this segment.

Low-limit cards see biggest jumps in defaults

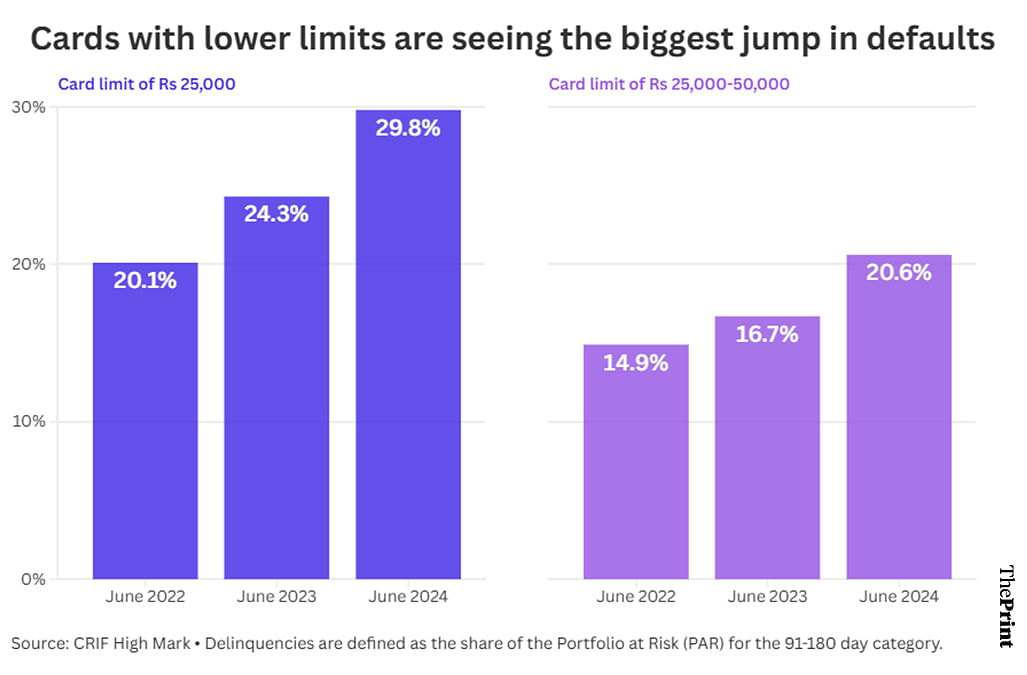

In keeping with these findings, data from CRIF High Mark showed that the biggest jump in default ratios was seen in cards with monthly credit limits up to Rs 25,000 and Rs 50,000.

The PAR 91-180 ratio for credit cards with a limit of Rs 25,000 jumped from 24.3 percent in the June 2023 quarter to 29.8 percent in the June 2024 quarter.

For the cards with limits between Rs 25,000-50,000, this ratio increased from 16.7 percent to 20.6 percent over the same period.

“The people with lower credit limits are typically the ones with lower incomes, who may not have qualified for a credit card under normal conditions,” Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at the Bank of Baroda, told ThePrint. “But there could have been situations where these norms were flouted because the customer said they were getting some other income.”

“Part of the issue is that people do like to consume, travel, and buy phones, and so they get tempted once they have a credit card,” Sabnavis added. “Crunch time is when you have to pay interest, and at some point you realise you don’t have money for it and so you default.”

Iyer, too, added that the level of scrutiny involved in issuing cards with high credit limits doesn’t really exist for low-limit cards.

“Low value customers, who are given a credit limit of Rs 50,000-1,00,000, will typically max out their cards each month. So, they are basically using these cards as a source to finance certain spending,” Iyer explained. “You will see a lot of their credit card spending being concentrated in non-essential or ostentatious purchases such as a car, phone, electronic item, or the stock market and F&O segment.”

When RBI & SEBI stepped in

While the situation has worsened as of the June 2024 quarter, both Iyer and Sabnavis feel that things will likely improve over the next few quarters as steps taken by Reserve Bank of India and SEBI take effect.

“We don’t expect delinquency ratios to become worse because there is a lot of regulatory scrutiny that has started happening on the unsecured loan exposure,” Iyer explained. “As a result, a lot of lenders are paring back their unsecured loans and also improving their credit underwriting standards. There’s a regulatory push to tighten these standards.”

The RBI had been warning banks about the sharp growth in unsecured loans through the bulk of 2023 until, in November that year, it finally took action. Through a notification, the central bank increased the risk weights for unsecured loans given by banks and non-banking financial companies.

This move, in essence, made it more expensive for lenders to give out such loans, and more expensive for borrowers to avail of them.

SEBI also took steps to curb excessive trading in the F&O segment by increasing the minimum contract size that could be bought—effectively putting them out of reach for low-income traders—and reducing number of weekly opportunities to trade in this segment, among other technical changes.

“Banks have been doing a lot more due diligence since November 2023,” Sabnavis noted, adding that the delinquencies being seen now are for cards issued earlier. “The growth in the credit card outstanding is still high, but it is much lower than what it was earlier.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Indians don’t know how their credit scores are calculated. CIBIL needs govt oversight

When all state governments are handing out doles, it’s hard to understand why people are defaulting on credit card payments. Already, the government has been providing free rations to 800 million people for the last 4 years. Add to that the plethora of freebies from state governments, people should be having a really good time. Especially, the ones at the bottom of the pyramid.

It’s strange that people are defaulting on credit card bills.

Good news for the bottom of the pyramid people. All state governments are handing out cash to them. Be it Laadki Bahin Yojana or Kejriwal’s offer of Rs. 2,100 per woman, they can pay off their credit card debt using such state handouts.

A win-win for everyone involved.