New Delhi: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI)’s high and unchanged repo rate has failed to make an impact—and it’s not just because of high food prices. An analysis by ThePrint has found that credit growth remained high and in double digits regardless of high interest rates. What made an impact were the RBI’s non-repo rate actions, such as clamping down on unsecured loans.

In its latest meeting earlier this month, the RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee kept the benchmark repo rate unchanged for the eleventh time at 6.5 percent, despite calls for rate cuts by ministers in the Modi government. The RBI governor at the time, Shaktikanta Das, argued that high inflation remained a concern.

The repo rate is basically the rate at which the RBI lends to commercial banks and, therefore, has an impact on the rate at which these banks lend to their customers, both companies and individuals.

The higher the repo rate, the higher the lending rate, and theoretically, the lower the credit offtake from these banks as loans become more expensive. This lower credit offtake is meant to reduce the supply of money in the economy, thereby lowering inflation.

One criticism of this policy has been that inflation in India has been driven by high food prices over the past year and a half or so, something the repo rate cannot control. The analysis by ThePrint shows that the repo rate has failed to control even the factor that it can directly impact—credit offtake.

The data shows that the high and unchanged repo rate had a very short-lived impact on the borrowings of households and companies, with growth in credit to both these categories rebounding quickly.

What finally did curb growth in personal loans was not the high repo rate but the RBI’s other steps to hit the brakes on unsecured loans.

These findings assume significance in the run-up to the February meeting of MPC, which will be the first under the new RBI governor, Sanjay Malhotra.

Borrowers shrug off high interest rates

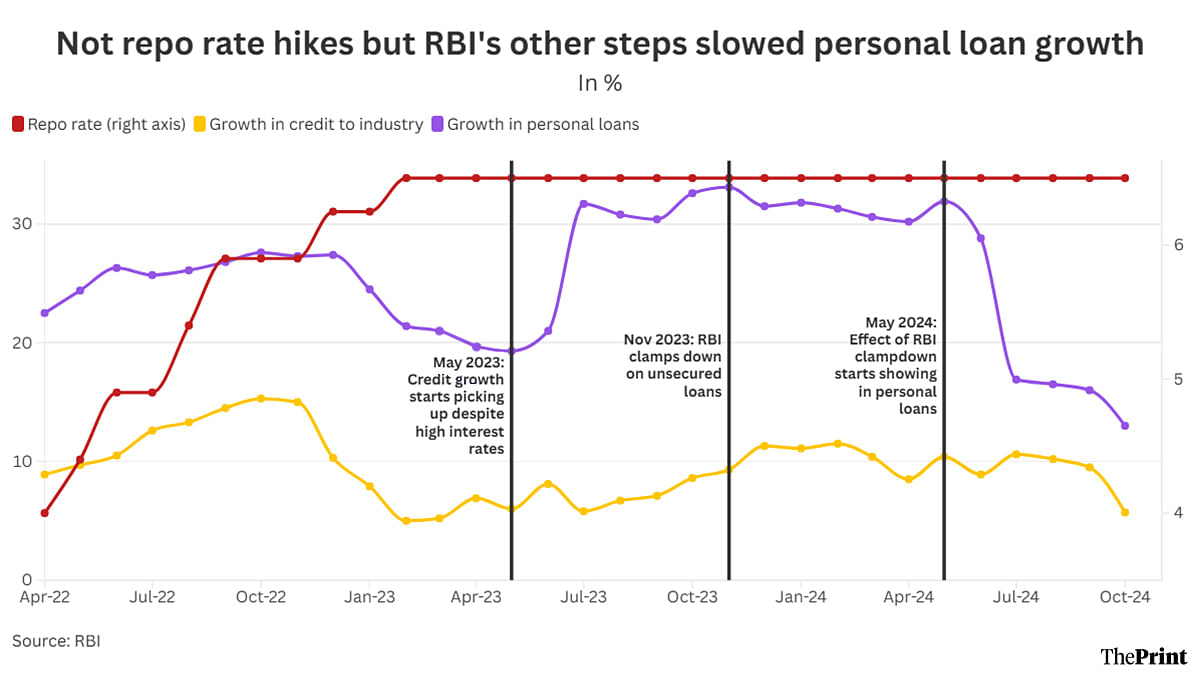

The MPC increased the repo rate in stages from 4 percent in April 2022 to 6.5 percent by February 2023 in an attempt to control rising inflation. This series of rate hikes was accompanied by a sharp slowdown in credit growth.

The growth in personal loans, for instance, slowed from a staggering 27.6 percent in October 2022 to 19.3 percent by May 2023. Growth in loans to industry slowed from 15.3 percent in October 2022 to 5.2 percent in March 2023.

This effect was, however, short-lived. What followed was surging growth in personal loans—driven by unsecured loans—and accelerating growth in loans to industry.

Even though the repo rate had been a high 6.5 percent for five months by July 2023, the growth in personal loans jumped to nearly 32 percent and remained above 30 percent till June 2024, nearly a year later.

Similarly, growth in loans to industry steadily accelerated to 11.3 percent by December 2023 and remained hovering about the 10 percent mark until October of this year, despite the repo rate being unchanged for 16 months.

Economic growth & high inflation likely spurred borrowings

The reason for this strong growth in credit was likely driven by two reasons, according to economists. The first was that this period also saw strong economic growth, creating an ‘income effect’. This effect happens when strong economic growth creates the perception that demand will also grow strongly, and so companies take loans to expand and meet this demand.

“There is an income effect and there is a price effect,” D.K. Srivastava, the chief policy adviser at EY India, explained. “The repo rate represents the price effect, which is the cost of borrowing. But since we had robust economic growth rates in the post-COVID years, that generated a strong income effect, which overshadowed the price effect (the high repo rate) and therefore there was strong demand for credit.”

The second factor at play could have been that stubbornly high inflation—which the high repo rate was supposed to bring down—was actually pushing households to borrow more to meet their expenses.

“One can argue that part of this high borrowing was to finance consumption due to high prices, leading to increased borrowings by households,” said Radhika Pandey, an economist and associate professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Retail inflation during 2022-23 averaged a very high 6.7 percent, higher than the RBI’s upper bound of 6 percent. In this financial year, the expectation is that inflation will average 4.7-5 percent, also higher than the RBI’s target of 4 percent.

Finally, something did the trick & it wasn’t the repo rate

From May 2024 onwards, something interesting happened. The growth in personal loans started dipping sharply. From 32 percent in May 2024, the growth in loans to this category slowed to 13 percent by October, the lowest it had been for more than 2.5 years.

Personal loans account for about one-third of all credit given out by banks and NBFCs, and so this slowdown meant that the growth in overall credit offtake also slowed sharply—from 21 percent in May 2024 to 12 percent by October.

But was this because of the sustained high repo rate or due to some other factors?

In response to the 30 percent plus growth rate in personal loans, the RBI in November took other steps to clamp down on unsecured loans. The central bank issued a notification increasing the ‘risk weight’ of consumer credit and credit card loans given out by banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs).

The move required lenders to keep aside a higher amount of capital to back consumer loans, which basically made them more expensive for banks to give out, and correspondingly more expensive for borrowers.

“Last year’s increase in risk weights started showing their impact from May-June of 2024,” Pandey explained. “Since then, personal loans and loans to NBFCs have slowed significantly and NBFCs are now looking at non-bank sources to raise finance.”

Srivastava, too, noted that the repo rate increases and the decisions to keep it unchanged for so long did not have the desired effect in lowering credit offtake and, as a result, inflation.

(Edited by Sanya Mathur)

Also Read: Trouble at the bottom of the pyramid: 1/3rd of low-limit credit cards see defaults on bill payments