India is debating whether to open the country’s debt markets wider to foreigners, to as much as 8 percent of outstanding bonds, from 5 percent currently. A 1 percentage point increase in the limit may attract 800 billion rupees.

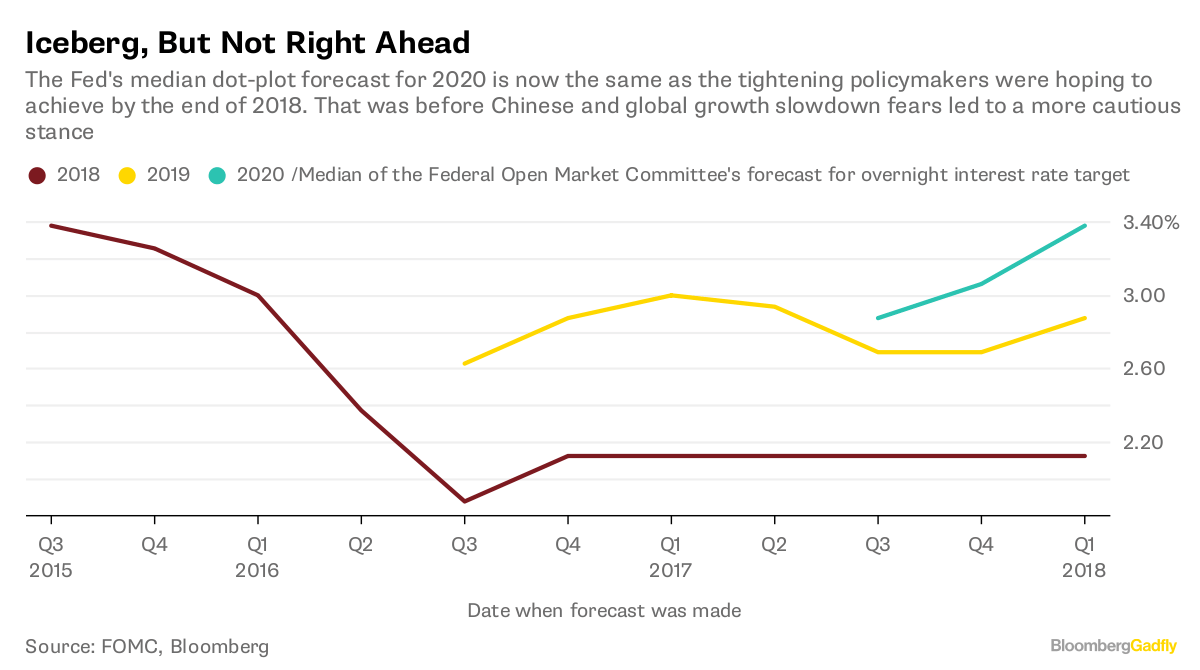

Jerome Powell’s debut rate-setting meeting as Federal Reserve chairman had few surprises. The quarter-percentage-point increase in the target for overnight U.S. interest rates was expected. An added relief was policymakers’ decision to leave their median forecast for end-2018 rates unchanged.

Yet the all-important dot-plot — committee members’ individual expectations — are telling Asia something more worrying. A possible fourth rate hike in 2018 hasn’t gone off the table; it’s now on the agenda for 2019.

The Fed is projecting end-2020 interest rates that are half a percentage point higher than what it predicted six months ago. By then, the U.S. central bank wants to achieve the tightening it originally hoped to finish this year.

That was when it had just been presented by a surprise Chinese devaluation. As Chinese and global growth concerns took the spotlight in 2016, the Fed’s aggression receded.

No longer, though. To China, the message is, “We won’t give you a Powell put.” For India, the takeaway is, “Get real about your bond meltdown.” Indonesia is being urged to stop clinging to interest rates that are too low to keep capital at home.

But let’s start with Hong Kong, which got a reminder to do a sanity check on its inflated real estate. The city’s pegged currency is close to hitting the lowest permissible point of its trading range; Powell’s rate increase has increased the odds the peg will get tested, forcing the city’s monetary authority to sell U.S. dollars, shrink the monetary base and raise Hong Kong dollar interest rates. Higher mortgage costs could expose the soft underbelly of the world’s least affordable housing market.

As long as Powell doesn’t raise U.S. interest rates too steeply, China can continue to push its companies — particularly property developers — to borrow cheap dollars overseas to keep domestic growth and asset prices on an even keel. That should give the newly appointed central bank chief, Yi Gang, room to steadily raise local money-market rates to force corporate deleveraging, President Xi Jinping’s top priority.

It would help China’s potential leader-for-life if Powell follows his predecessors and offers the markets a put option to limit losses. From the looks of it, the new Fed chair isn’t persuaded. Complicating matters, the yuan is strengthening against a weak dollar, hurting China’s trade competitiveness amid an escalating trade war with the U.S.

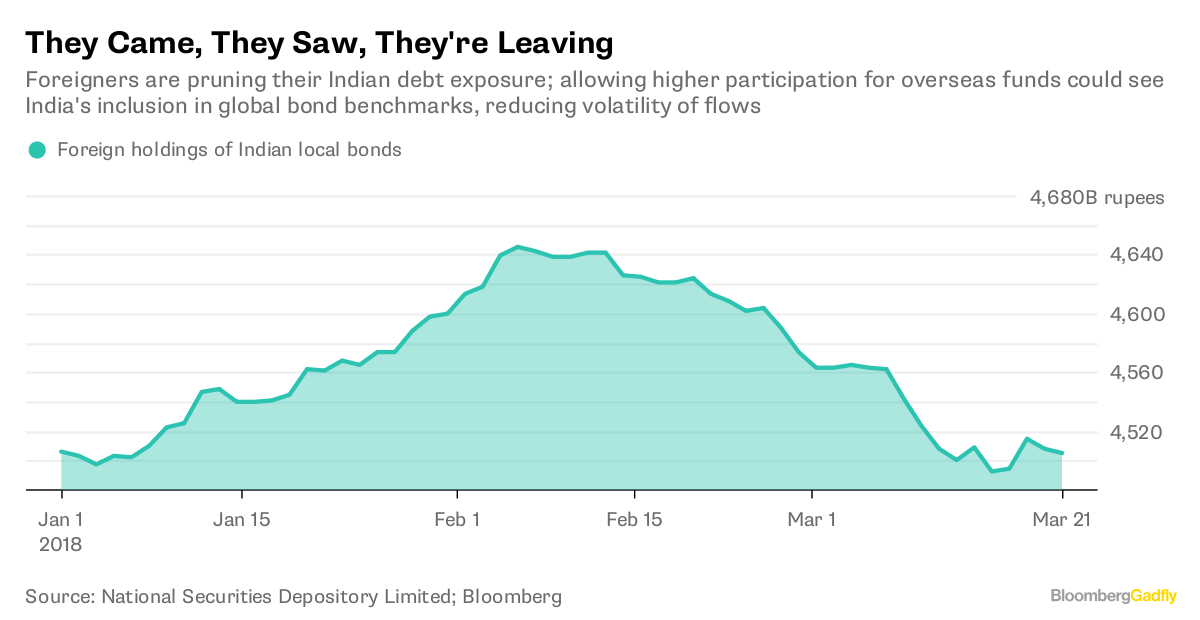

India, meanwhile, is debating whether to open the country’s debt markets wider to foreigners, to as much as 8 percent of outstanding bonds, from 5 percent currently. A 1 percentage point increase in the limit may attract 800 billion rupees ($12.3 billion), according to Nomura Holdings Inc.

That could be important because New Delhi’s financing needs are high. Local banks, the biggest bond buyers, are sitting on a $192 billion surplus of Indian government IOUs. Inviting foreigners to take up the slack could prevent surging yields from turning into a deeper bond-market rout, forcing further mark-to-market losses on fragile lenders. If India dithers, and Powell shows an inclination to tighten more quickly, international money managers may pull more capital out.

A similar problem faces Indonesia, where the central bank ran down its reserves by almost $4 billion last month to prevent an inflationary meltdown in the rupiah. Bank Indonesia is valiantly holding interest rates 1 percentage point lower than where they were three years ago. Its desire to squeeze maximum growth out of cheap money is understandable, but risky.

The Fed’s dots are knocking, suggesting an urgent need to put the house in order. Delaying rate increases at home can only raise the risk of capital flight.— Bloomberg

Financial repression has been a fact of life in India for a long time now. The government preempts too large a share of bank credit for its own borrowing programme. It also imposes suboptimal lending decisions on banks, through priority sector targets and other pressures that create NPAs. One has never understood why government bonds, which ordinary citizens cannot buy but, increasingly, foreigners can, yield more than bank FDs. Not just the Centre, the states too are on a slippery fiscal path. A prosperous state like Maharashtra is running a fiscal deficit of 3%, its public debt is surging to the five trillion mark. A time for caution.