To ensure equity between the states, poorer states should receive a greater share of union tax revenues as compared to better off states.

For the first time perhaps in living memory, there’s a spirited debate about the terms of reference of the finance commission – a body that most Indians, even the educated elite, have not even heard about, let alone care too much about.

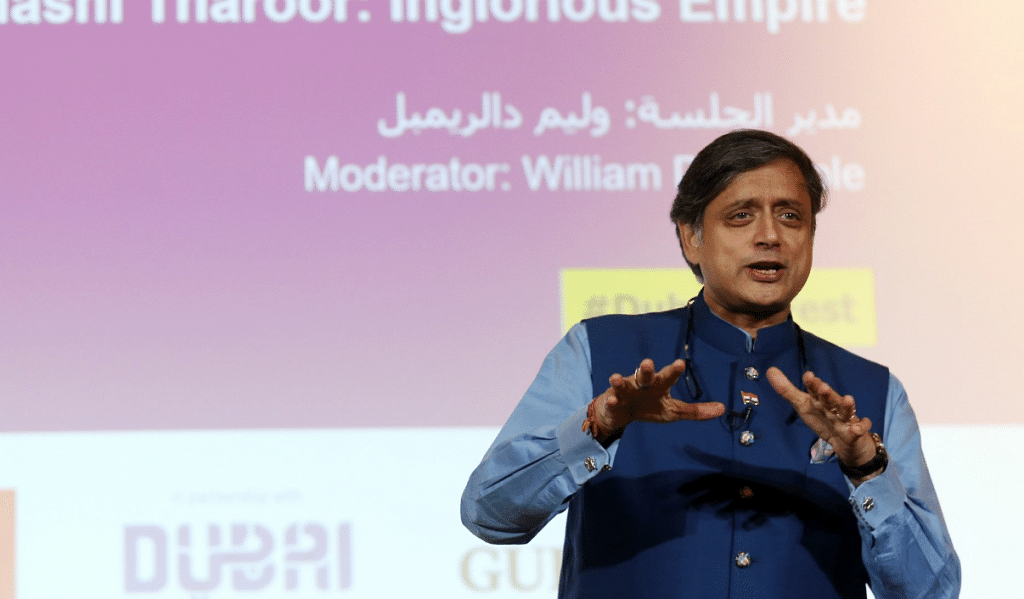

Shashi Tharoor’s piece, ‘Modi govt opens a Pandora’s Box: States can lose political clout if they develop well’, is an important intervention in this debate, come as it does from a sitting member of Parliament from a national party. His piece is, however, built on four myths about the Centre-state relationship. If not debunked, it could vitiate the discourse. This piece is a response to the four stated (and one unstated) myths that form the central part of Tharoor’s piece.

Myth 1: The finance commission (FC) is being asked to use 2011 data for the first time

While the 15th FC’s terms of reference (ToR) are the first to explicitly state it thus, it won’t be the first time the body has been asked to use 2011 census data in making its recommendations. The ToR of the 14th FC also required it to “take into account demographic changes that have taken place subsequent to 1971”. This meant that the 14th FC gave the 2011 population estimate a weightage of 10 per cent as “demographic change” in determining the shares of states in the divisible pool of Union tax revenues. Seen in that perspective, the 15th FC only carries forward a previous (necessary) move to update the population statistics in allocating Union revenues among the states.

Myth 2: The south is “subsidising” the north

Tharoor references Karnataka chief minister Siddaramaiah’s Facebook post outlining figures that suggest southern states receive less by way of Union tax revenues than those like Uttar Pradesh, even though they “contribute” more. This isn’t the first time this comparison is being made and, while the numbers are correct, it must be pointed out that this sort of comparison is misleading. Union taxation applies on a deeming fiction that if a return is filed in a state, then tax is attributable to that state. It is impossible to segregate an individual tax return on the basis of the source of income. Merely because an entity located in Mumbai files tax returns with the local office, it does not mean that, as a matter of fact, all the tax revenue is only attributable to economic activity in Maharashtra. On this ground, if any state has to have a grievance, it must be Delhi, which, by this logic “contributes” Rs. 1,08,882 crore in direct taxes to the Union government and receives nothing from the divisible pool because it is not a “state” as understood constitutionally.

On the other hand, if collection of taxes is correlated closely with contribution, the northeastern states and Jammu & Kashmir would get little by way of a share in the divisible pool of Union taxes.

Myth 3: The ‘cow-belt’ states have comprehensively “failed” to improve their own development indicators, notably female literacy and women empowerment

From the vantage point south of the Vindhyas, it is tempting to see the whole stretch from Rajasthan to Bihar and Jharkhand as one irredeemable black hole of human despair and stagnation. One only needs to compare the human development indices between northern and southern states to see why this might be a justified conclusion. This, however, obscures the very real progress that has been made even in the so-called ‘BIMARU’ states in improving indicators in the last couple of decades.

Female literacy increased by 20.21 percentage points between 2001 and 2011 in Bihar, by 17.34 and 17.04 points, respectively, in Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh. Of course, the picture is not entirely uniform: in the same period of time, female literacy improved by only 11.04 percentage points in Haryana, 9.73 in Madhya Pradesh, 8.81 in Rajasthan and 8.74 in Chhattisgarh. Much more can be done and needs to be done, but one wonders how cutting off much needed revenue to these states will help “incentivise” investment in female literacy.

Myth 4: Giving north Indian states more money means “incentivising population growth”

The most pernicious myth of all, repeated by Tharoor, is that giving north Indian states a greater share of Union tax revenues is akin to “incentivising population growth”. This is, once again, based on a snapshot of the total fertility rate of women in different states, without taking into account the progress made across states in reducing this in the last decade or so.

According to the latest available data, while total fertility rates (TFRs) in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are still a relatively high 3.1 and 3.3 respectively, these are an improvement from 2000, when the figures were 4.7 and 4.5, respectively. In all the ‘BIMARU’ states, the TFR has decreased fairly dramatically over the last two decades, and if the trend continues, will fall for the next decade or so. No doubt, decadal population growth is greater in the north Indian states than the south Indian ones, but we must not assume that this will always be the case.

Myth 4.5: Share in Union tax revenues is a “reward” for improving development indices

This isn’t a myth so much as a misconception. There is no basis to contend that a share in Union tax revenues is some sort of a reward for “performance”. In the last few FC recommendations, the single largest factor that determined a state’s share in the Union tax revenue is the “income distance”. This is arrived at by calculating the difference between the per capita GSDP of a state with that of the richest, large state in India (in the 14th FC, it was Haryana). The purpose of this is to ensure equity between the states – poorer states should receive a greater share of Union tax revenues as compared to the ones better off.

If they didn’t, they would never be able to climb out of the poverty trap they’d be confined to.

As necessary as it is to push back against the Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan agenda of the Union government (and one takes no issue with Mr Tharoor on this), it can’t come in the form of an aggrieved sense of entitlement or a misplaced sense of victimhood among the southern states. The better-off states are already less dependent on Union tax revenues than the less well-off states, and increasing inequality within the Indian union cannot possibly be a solution to this problem.

Tharoor is right in pointing out the larger tensions that are likely to bedevil the Indian Union in the years to come, but does not offer a concrete solution to address them. It is beyond the scope of this piece as well to offer a comprehensive one, but, suffice it to say, whatever solution is proposed, it must be an affirmation of the federal and democratic values at the core of the Constitution and an acceptance that “development” does not require compromise on either of these.

Alok Prasanna Kumar is a senior resident fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.