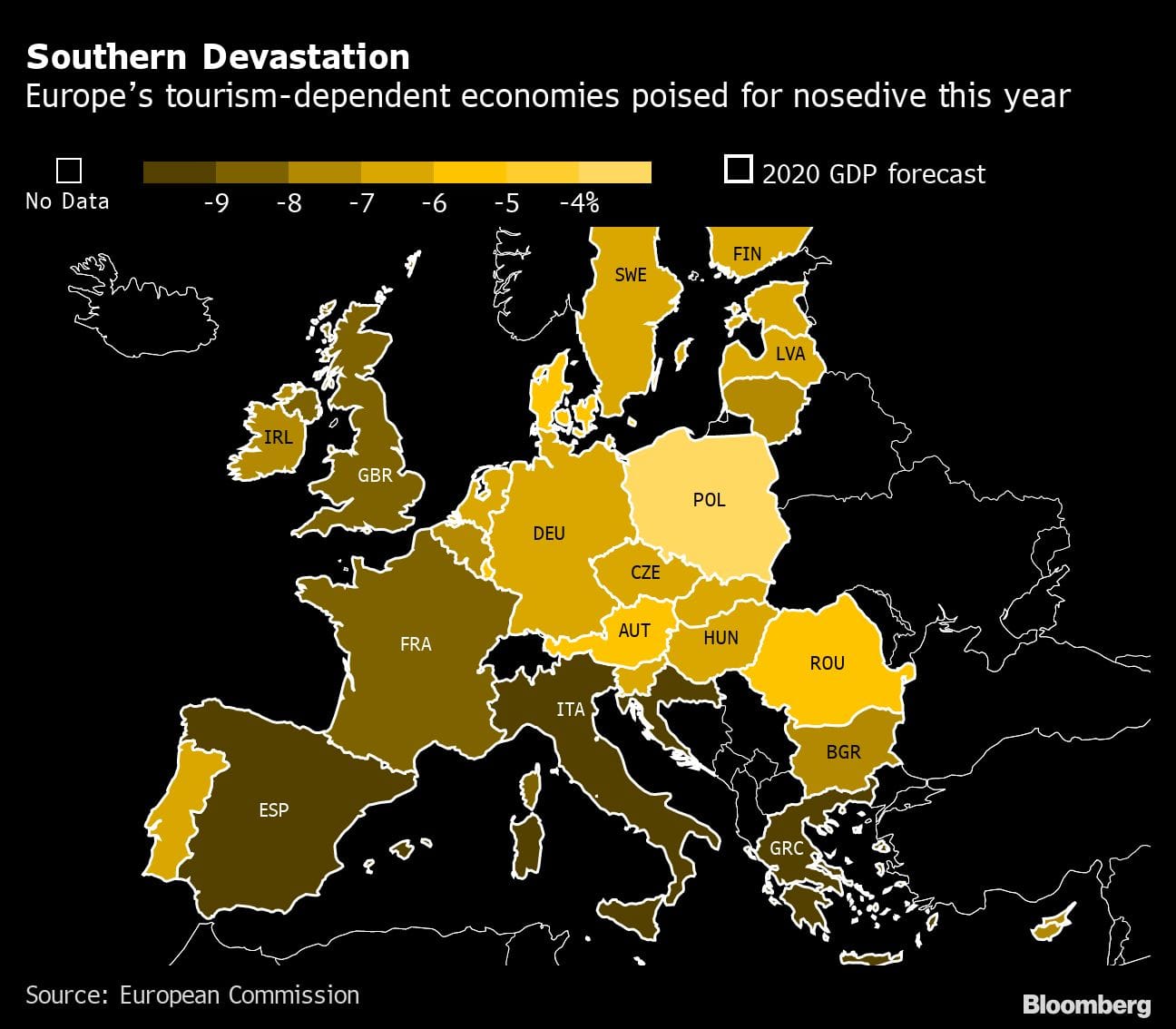

Rome/Berlin/Zurich: The coronavirus is threatening to turn the long-lasting fault line cleaving Europe between its richer north and poorer south into an economic chasm putting its currency at risk.

In Rome, some churches are now food banks, charity boxes crop up in city squares and the 15th-century hotel where philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once stayed is giving away its mattresses from a pile by the entrance. Paolo Stella, a 57-year old barber, says he’d rather burn his shop down than reopen in the current conditions, with Italian government dithering over a 55 billion-euro ($60 billion) stimulus package adding to the problems.

Five hundred miles north near the German city of Stuttgart, 63-year-old entrepreneur Ernst Prost has rejected state aid despite a 25% hit to sales of his high-grade motor oils. Instead of letting people go, he dipped into his company’s cash reserves to pay nearly 1,000 employees a bonus of 1,500 euros with the conviction it would help his firm emerge stronger from the crisis.

The diverging fortunes of the two halves of the monetary union are reviving the age-old question of whether Italy can stick with the currency. The euro was supposed to elevate living standards across the board. But the South fears it’s being left behind.

“It’s a really a dangerous moment,” said Jana Puglierin, head of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Italy, Spain and even France, to an extent, were still recovering from the sovereign debt crisis when the coronavirus swept in, public finances strained by multiple bank bailouts and repeated recessions, their healthcare systems frayed by years of austerity. The German-dominated north has had more success in containing infections and more fiscal firepower to ride out the economic pain.

Chancellor Angela Merkel has vastly outspent her allies in the European Union with stimulus equal to around 4.5% of gross domestic product. Germany, which in the end agreed to bail out Greece when push came to shove, is now under pressure to ditch its red lines again to ensure the EU holds together.

For Prost, a businessman, the answer should be straightforward. “We can’t just sit by and watch Italy and Spain go to the dogs,” he said in an interview. “That can’t be in the interest of the European idea.”

German GDP will be less than 1% smaller by the end of next year, according to the EU Commission’s May 6 forecasts. Italy’s will have shrunk by 3.6%, pushing its debt to 154% of output — way beyond the level Greece was at when it triggered the euro area’s last financial crisis.

“The debt dynamics and public finance dynamics were already bad,” said Nick Kounis, head of macroeconomic and financial market research at ABN Amro Bank. “Now they look terrible.”

French President Emmanuel Macron says that if Merkel and other fiscal hawks like the Dutch and Austrians refuse to support either joint bond issuance or handouts from a centralized fund, then the whole edifice could crumble. The idea of putting taxpayers’ on the hook for other countries’ spending is a prospect that makes many politicians in northern Europe nervous.

Changing Attitudes

Asked about Italy’s predicament in an interview this week, Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz was clear: “They wouldn’t be able to handle this situation without the help of the EU and countries like Austria. But I don’t think that the idea of shared debt is the right answer.”

Against the backdrop of arguments over how to borrow, the European Central Bank is leading the response to the current crisis with monetary and market-calming measures providing a lifeline for Italy. Yet more economic divergence will exacerbate a problem the institution has faced for years: how to conduct monetary policy in a region with vastly different growth rates and underlying economic circumstances.

Its stimulus push of the past few years stoked widespread discontent in Germany, in particular at negative interest rates that curbed returns for savers. The legality of quantitative easing, the ECB’s other signature policy of recent years, also faces an unprecedented challenge from the German constitutional court.

However, pressure to extend more support to the South is now bubbling up in Germany’s economic heartlands, where executives like Prost worry about crucial export markets. “If our customers in Italy or Spain go bankrupt, then the German economy will be hit the very next day.” Two-thirds of his company’s revenue comes from overseas.

Germany’s biggest business lobby this week issued a joint statement with its counterparts in France and Italy, calling for “a strong element of true fiscal solidarity.” They specifically asked EU leaders to include direct handouts as well as low-interest loans.

If, and when, that help comes it might be too late for the millions of Italians kept waiting for their own government’s emergency aid to come through. Renato Astrologo, who runs a popular trattoria in central Rome, is worried.

“We filed furlough requests two months ago, but we haven’t received any money,” he complained. “That’s not just a delay, it’s a distortion, and I am advancing the money to my employees who have to pay for rent and food.” – Bloomberg

Also read: Covid-19 deaths decline in Europe as countries begin to ease out of lockdown