New Delhi: Even though the Indian stock markets are witnessing a strong bull run, the markets themselves are much more resilient to external shocks than during the “mother of all bull runs” in the 2003-08 period.

An analysis by ThePrint shows that market corrections—or dips—over the last few years have been shallower, and recoveries have been much quicker.

What’s driving this resilience? According to experts, it is because of the rising importance of domestic investors and the related diminished impact of foreign institutional investors who used to “call the shots” earlier.

Bolstering this is a robust economy, strong corporate sector performance, and the adoption of an optimistic ‘buy on dips’ strategy by India’s retail investors.

ThePrint analysed the current stock market bull run—which saw the Sensex rise from its COVID-19-induced fall to 26,000 in mid-March 2020 to the current levels exceeding 82,000—and compared it with the bull run seen between 2003 and 2008. That period saw the Sensex rise from around 3,200 in early 2003 to 20,000 by early 2008.

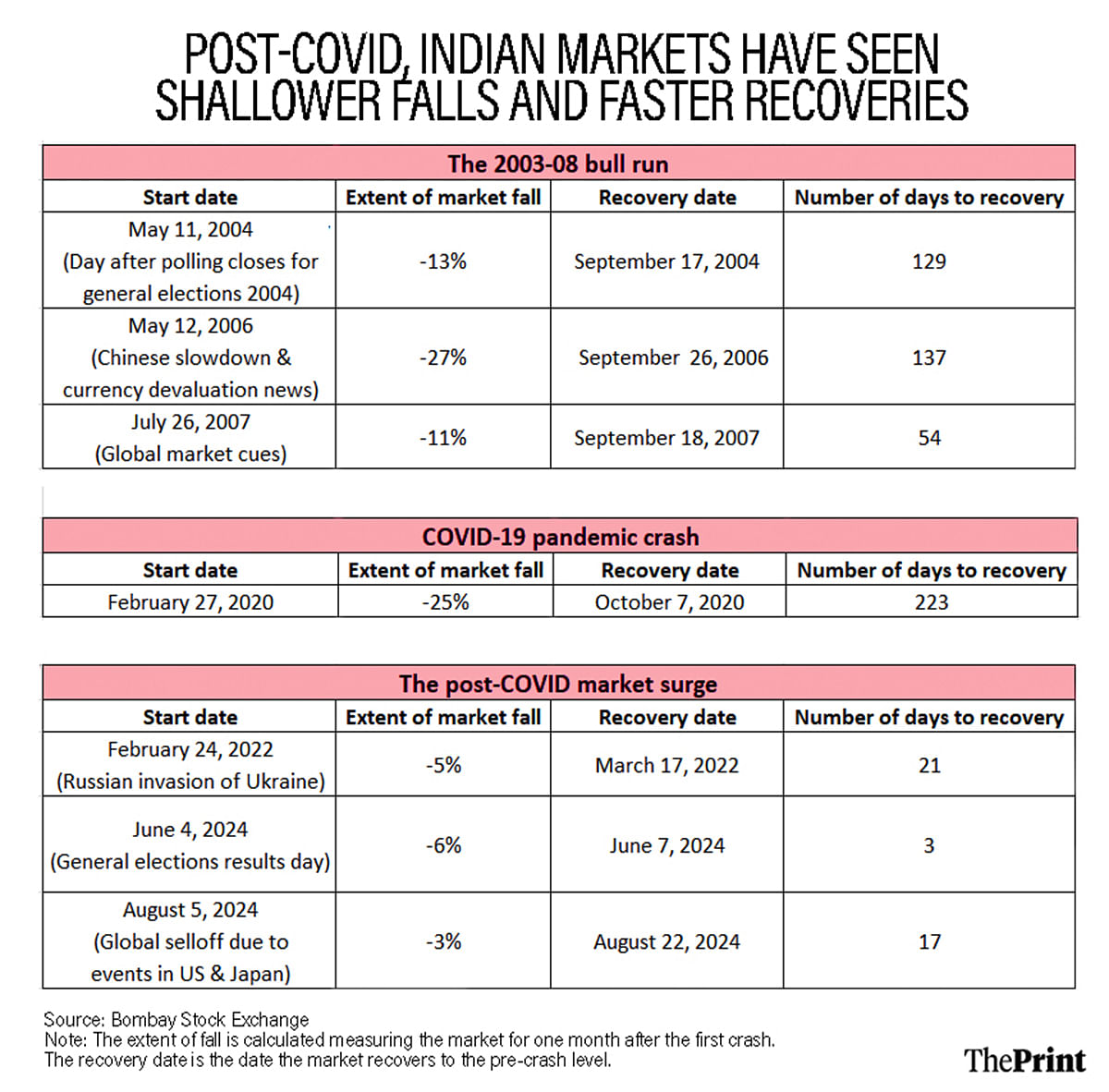

The analysis found that the stock market corrections during the 2003-08 period were deeper than corrections seen in the current bull run. Earlier corrections also lasted longer than they do now, with the current markets being able to bounce back in just a few days.

“The markets are more resilient now than before, particularly if you compare the ongoing market rally with the one we had between 2003 and 2008,” explained V.K. Vijayakumar, chief investment strategist at Geojit Financial Services. “That bull run was called the ‘mother of all bull runs’.”

“But during that bull run, we had about three corrections of more than 10 percent and one of more than 20 percent,” Vijayakumar added. “So it was a rally characterised by corrections, and these corrections lasted for a few months, not just 1-2 days.”

What is happening now is that the markets correct for just a few days before bouncing back, he noted.

Also Read: Why India’s digital banking push is giving RBI nightmares. Hint: The Credit Suisse collapse

From deep & long to shallow & short

Data shows that the corrections in India’s stock market have historically been driven by both domestic and international events. The first major correction in the 2004-2008 bull run, for example, started on 11 May 2004—the day after polling ended for the 2004 general election when the exit poll results would have been made public.

Over the rest of May that year, the market fell a cumulative 13 percent. It took till 17 September 2004—129 days later—for the markets to recover to their previous level.

In May 2006, however, it was a slowdown in the Chinese economy and the devaluation of its currency that caused markets to crash around the world, including in India. The markets fell 27 percent, cumulatively, in the aftermath of these developments and took 137 days to recover.

The Indian markets crashed again in response to global cues in July 2007, by a cumulative 11 percent, and took 54 days to recover.

In comparison, the ongoing post-COVID market surge has seen much shallower falls and significantly quicker recoveries. For example, the Indian stock markets fell just 5 percent in the days following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, bouncing back to their previous levels in just 21 days.

Domestic factors, too, don’t spook the market as much. The 2024 general election results saw the markets fall just 6 percent on 4 June 2024, the day of the results. It took just three days for them to recover.

“Prior to the results, if somebody had asked me what I would have expected from the market if the BJP did not win a single-party majority, I would have said the market would have corrected by 10-15 percent,” Vijayakumar said.

“The market did correct, but it was a smaller correction and lasted only one day or so.”

Even more recently, 5 August 2024 saw a global market selloff due to the dual impact of weak US employment data and the Japanese central bank’s decision to raise interest rates. The Nikkei index fell 12.4 percent that day, its sharpest fall since 1987.

The Indian Sensex fell 3 percent and, although it took relatively longer to recover, it did so within just 17 days.

A resilience built on domestic strength

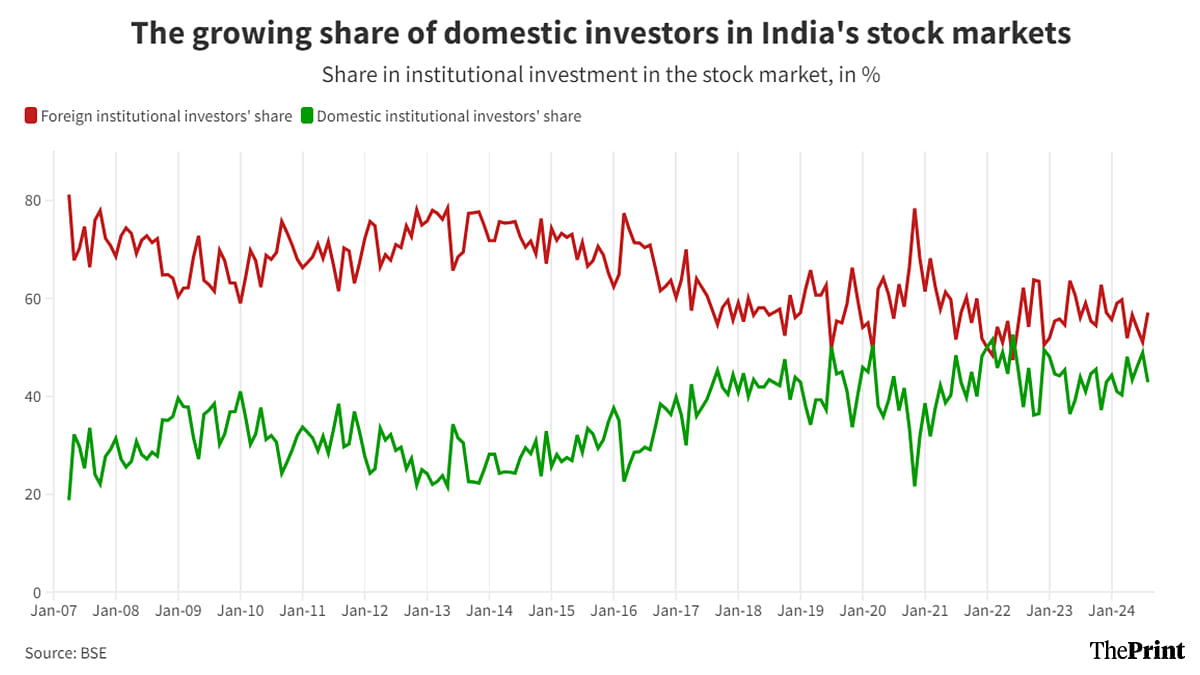

“Earlier, if you looked at the Indian stock market, it used to be hugely influenced by foreign institutional investors (FIIs) and any foreign event would lead these FIIs to cut down their risk in every market, including in India,” said Rajkumar Singhal, CEO of Quest Investment Advisors explained.

“The impact of any global event used to get exaggerated in the Indian market.”

Now, on the other hand, domestic institutional investors (DIIs) are in a much stronger position.

“What is happening is that we are seeing very short and swift market corrections and very quick recoveries, and that is because of the domestic inflows into the market,” Vijayakumar concurred. “FIIs used to call the shots previously, that is not the case now.”

Stock exchange data shows that FIIs made up about 81 percent of the institutional investment in India’s stock markets in April 2007. This has since fallen to 57 percent as of August 2024. On the other hand, the share of DIIs has risen from about 19 percent in April 2007 to 43 percent in August this year.

“This time around, because of local liquidity, the impact of overseas volatility does not impact the domestic markets as much,” Vikas Khemani, founder of Carnelian Asset Advisors.

Retail investors who’ve learnt to ‘buy on dips’

The other factor adding to the Indian stock market’s resilience is the behaviour of the retail investor. A significant portion of these investors, comprising large parts of the general public and the youth, entered the market following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Take the examples of the Yen carry trade event (5 August 2024) and before that the (general elections) results day,” Singhal said. “One was a global event and the other was India-specific. On both days, the markets reacted negatively but on both days, the retail participants actually bought on those days.”

“A good reason for that is that, since COVID times, the equity markets have generated pretty decent returns so there is a recency bias because people have seen returns in the market,” he added.

Both Singhal and Vijayakumar explained that, earlier, only canny investors used to follow the strategy of ‘buy on dips’—which is when investors buy more stocks when the market falls with the expectation that it will rise again.

Now, however, many retail investors are following this strategy because their entire experience of the market has been one of a rally. That is, these new investors believe that every correction will be followed by a quick recovery, so they feel it’s a smart idea to buy more stocks when those corrections happen.

“Also, for the retail investor, equity works out to be the most tax-efficient product, and so more and more of the younger crowd is moving into the segment,” Singhal added. “And they have made money, so their confidence in the markets is also high, so when the market reacts negatively, these investors tend to buy.”

Another difference in the behaviour of retail investors now versus earlier is the phase of the bull run that they enter the markets. According to Vijayakumar, retail investors used to enter the markets during the tail end of the bull run, as they did in 2007, just a year before the Global Financial Crisis put an end to the market rally.

“This time, the difference is that the retail investors have been investing right after the COVID crash, which is when this rally began, and more and more retail investors have been joining,” Vijayakumar explained.

Structural shift in economy and corporate behaviour

The final factor lending resilience to the Indian stock markets is the relatively strong performance of the Indian economy—including corporate India—and the falling cost of capital in the country.

“This time around the earnings growth is quite broad-based,” Khemani of Carnelian pointed out. “It is across sectors, including manufacturing, financial services, consumption, infrastructure, and the entire services space. Also, the sustainability of the earnings growth is very visible.”

This, coupled with overall economic growth expected to be 7 percent in the current financial year—which would be the fourth consecutive year of 7 percent growth or higher—has lent the market resilience, he said.

The other corporate behaviour Khemani highlighted was their lower dependence on foreign borrowing.

“In the previous cycle, borrowing by Indian corporates abroad was far higher,” he explained. “Today, because the cost of capital in India has come down, our borrowing abroad is hardly anything as compared to the previous cycle.”

“So when you have not borrowed abroad, your dependence on the overseas liquidity conditions is not there and as a result, even if something like the Yen carry trade issue occurred, nothing much happened to the Indian economy or the markets because Indian corporates are not aligned to that,” he added.

(Edited by Sanya Mathur)

Also Read: Discarded privatisation plans? Number of operating public sector companies rises by 20 since 2014

Excellent analysis. We yet need to know how much of this was driven by individual retail interest Vs DFI