New Delhi: Just a few years ago, Bangladesh was touted as one of the fastest-growing economies in Asia. Economists hailed its transformation from a “basket case” to one of the region’s surprise success stories. Even during the growth years, though, the nation’s banking system was seen as its Achilles heel.

Today, persistently high inflation, tight liquidity conditions, weak governance and high non-performing loans burden the nation’s economy, with experts blaming bad loans during Sheikh Hasina’s term and poor financial management during economist Mohammad Yunus’s rule as the key factors.

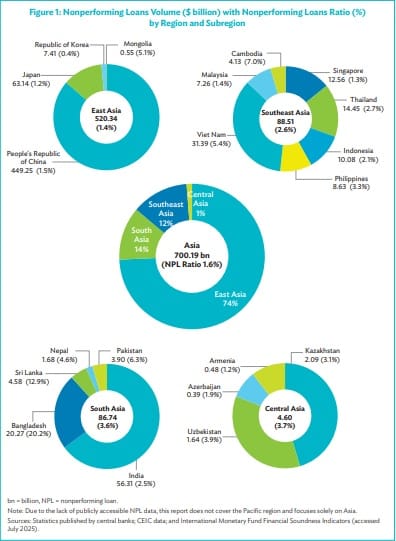

By December 2024, Bangladesh recorded the “weakest banking system in Asia”—20.2 percent (Tk 3,45,765 crore) of total loans were in default—the highest in the region, according to the Asian Development Bank’s 2025 report on ‘Non-performing Loans Watch in Asia’. In comparison, by December 2024, India’s non-performing loans were 2.5 percent of total loans, while Pakistan’s were 6.3 percent. By June 2025, Bangladesh’s non-performing loans had risen to 27.09 percent or Tk 5,30,428 crore, as local media reported, citing Bangladesh Bank.

The country’s $20.27 billion stock of distressed assets represents a 28 percent year-on-year increase, highlighting what the ADB described as the region’s “most fragile banking system” in its report published last month.

Other South Asian economies—India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka—all saw declines in their NPL ratios last year, while Nepal experienced only a slight rise of 0.9 percentage points. India, the region’s largest economy, reduced its NPL ratio to 2.5 percent from 3.4 percent, supported by broad-based banking reforms.

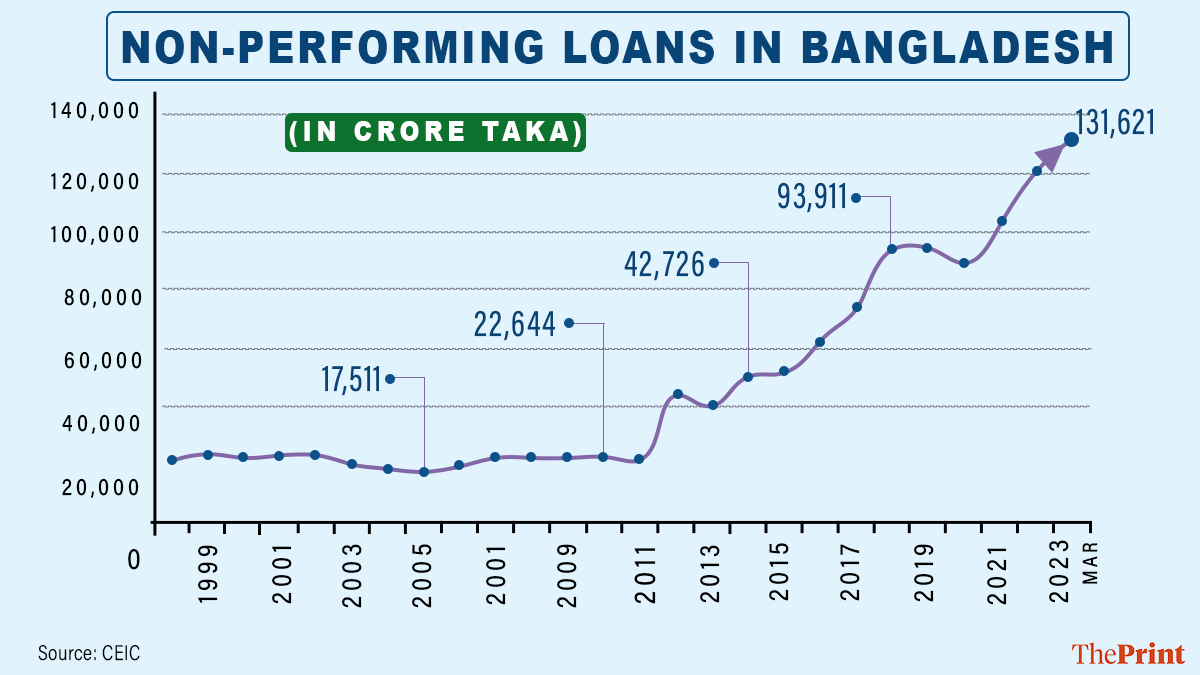

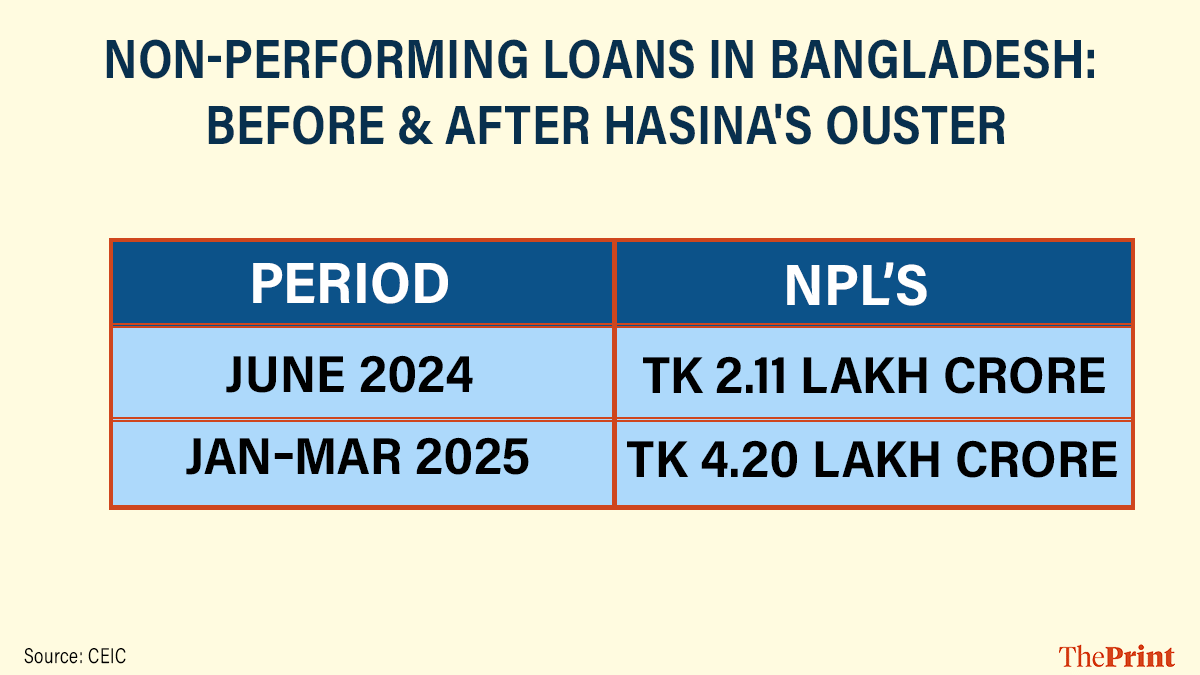

At the heart of Bangladesh’s banking system crisis are spiralling non-performing loans, which jumped from Tk 22,481 crore when the Awami League came to power in 2009 to Tk 2,11,000 crore or 12.5 percent of total loans by June 2024, right before Bangladesh’s July uprising that brought down the Hasina government. “Many politicians and unscrupulous businessmen treated the banks like personal wallets. They borrowed money, only never to return it. There was an unholy alliance where one director borrowed from another’s bank, using inflated collateral,” Bangladeshi economist Mustafizur Rahman, Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), told ThePrint.

Rahman described how “corrupt borrowers”, with the connivance of auditors and bank officials, overstated the value of collateral—showing Tk 10 crore worth of property as Tk 500 crore—to secure massive loans. Much of this money was then siphoned abroad.

“Now, when the central bank tries to recover these loans, they find the assets are worthless. The money has been taken out of the country, and recovering it is extremely difficult,” he said.

However, Rahman described the financial system as “in bad shape, but not collapsed”.

According to a World Bank report, Bangladesh’s impressive economic growth over the past decade has been challenged several times in recent years. Real GDP growth is estimated to have eased slightly to 4 percent in FY25, down from 4.2 percent in FY24. Despite this moderation, inflation remains high, vulnerabilities within the financial sector have intensified, and investment growth has slowed.

Also Read: Bangladesh & Pakistan resume economic talks after 20 years, Islamabad eyes jute imports

A freefall and a shifting blame game

The interim administration hasn’t been able to contain the crisis. The amount in non-performing loans nearly doubled under Yunus in a year, from Tk 2,11,000 crore to 5,30,428 crore.

The Bangladesh Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement (July to Dec 2024) shows that when the current interim government took office in August 2024, the economy was facing significant macroeconomic challenges. These included persistently high inflation, rapid currency depreciation, dwindling foreign exchange reserves, growing external payment arrears, tight liquidity conditions, weak governance, and high non-performing loans.

In response, Bangladesh Bank (BB) outlined a strategy that stressed controlling inflation, stabilising the exchange rate, rebuilding reserves, and restoring confidence in the banking sector through improved governance. To achieve these goals, the bank maintained a tight monetary policy stance and adopted a fully flexible, market-based exchange rate regime. The central bank also initiated a broad range of reforms in the banking sector.

However, according to Mamunur Rashid, associate professor of International Finance at UK’s Canterbury Christ Church University, Bangladesh’s rising default loan crisis is driven by recent political turmoil and poor financial management under the Yunus administration. “The default loan crisis is not just a legacy issue; it’s a 50-year-old culture of financial indiscipline that has persisted since Independence,” Rashid told ThePrint.

“By allowing mob violence and arson to devastate businesses, particularly those linked to opposition groups, the government has itself fuelled the growth of bad loans,” Rashid said, speaking about the Yunus administration.

He added that the problem had been compounded by Bangladesh Bank’s heavy domestic borrowing, which drained liquidity from the private sector, pushed interest rates higher, and made it nearly impossible for borrowers to reschedule existing loans.

According to Bangladesh’s Economic Update and Outlook report by the General Economics Department, the private sector’s credit growth hit a 21-year low of 6.82 percent in February, signalling deepening distress. According to the latest GED report, at the end of August, it dropped to a historic low of 6.35 percent, significantly below the bank’s targets. The trend showed “a deep-seated reluctance by businesses to invest and expand”, noted the report, attributing the trend to “high interest rates, cautious lending, political and economic uncertainty”.

The benchmark interest rate, according to Bangladesh Bank, is 10 percent as of February 2025—the highest since 2008—making it difficult for borrowers to reschedule existing loans and further dampening private investment.

Meanwhile, the public sector credit growth was high—16.59 percent—in August, given the “government’s need to finance its fiscal deposits and expenses, exacerbated by a shortfall in tax revenue collection”.

Bangladeshi daily newspaper The Business Standard reported that political instability and low private investment led to a Tk 51,696 crore increase in banks’ excess liquid assets, which reached Tk 2,15,000 crore by December 2024, up from Tk 1,63,000 crore in December 2023. Despite higher liquidity, cash holdings fell by Tk 2,291 crore.

Before the July uprising and the August 2024 floods in Bangladesh, inflation was already at its highest level in decades. Foreign reserves were falling, the taka was weakening, and remittance inflows declined sharply after expatriate Bangladeshis boycotted transfers during the July uprising.

Post the fall of the Hasina government, senior bank officials, including the central bank governor, fled—an event economists described as unprecedented in Bangladesh’s history.

“In the history of the world, not just Bangladesh, you rarely see a central bank governor flee after a political change,” Mustafizur Rahman said.

Economic test

Now, Bangladesh faces its biggest economic test in decades. It is a test of restoring trust, restructuring institutions, and preventing a full-blown financial breakdown.

Local media reported that Bangladesh’s capital shortfall of 24 scheduled banks surged to Tk 1,55,867 crore by June 2025, up from Tk 1,10,260 crore across 23 banks in March. This jump reflects many concealed defaults that surfaced after the interim government took office, exposing the extent of NPLs.

Struggling to maintain required provisions or funds set aside to cover potential future losses, banks are rapidly losing capital, which poses a serious threat to the country’s financial stability.

The shortfall reportedly affects four state-owned commercial banks, two specialised banks, eight Islamic banks, and 10 private commercial banks.

One of the most alarming concerns is the persistence of NPLs.

As of December 2024, state-owned banks reportedly had a staggering 42.8 percent of loans as “non-performing”. This reflects not only inefficiencies in loan recovery but also widespread mismanagement in the sector.

In an unprecedented step, Bangladesh Bank has reportedly announced plans to merge the five struggling Islamic banks—First Security Islami Bank, Social Islami Bank, Global Islami Bank, Union Bank, and Exim Bank—into a single state-owned institution, known as United Islami Bank.

According to the Policy Research Institute’s Principal Economist, Dr Ashikur Rahman, while Bangladesh’s macroeconomic indicators have begun to stabilise, the investment climate remains distinctly fragile.

Inflation is on a moderate downward trend, the exchange rate is steady, and foreign reserves now cover more than five months of imports. However, investors are being cautious because of the political uncertainty,

“Investors continue to hold back amid a cloud of political uncertainty, dampening prospects for new enterprise, job creation, and poverty reduction,” Rahman told ThePrint. “In essence, Bangladesh is walking a tightrope: macro stabilisation has been achieved, but without decisive reforms on both the fiscal and monetary fronts, accompanied by political stability, this stabilisation may not translate into an economic turnaround.”

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has consistently flagged poor corporate governance, political interference, and a pervasive culture of willful loan defaults as major obstacles to reforms. Moreover, Bangladesh Bank’s limited autonomy has undermined its ability to act as an effective regulator, weakening oversight and enforcement mechanisms.

Another pressing concern is the rise of so-called “zombie” banks or institutions kept alive through repeated central bank bailouts despite being financially insolvent. Rather than allowing for necessary restructuring or consolidation, Bangladesh Bank has extended loan support to these weak banks, effectively postponing rather than solving the underlying problems.

These measures, economists say, have limited the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves and heightened systemic risks, leaving the financial sector vulnerable to both internal and external shocks.

Also Read: Don’t call student protests a revolution. It was a terror attack on Bangladesh: Sheikh Hasina

Reforms and recalibration

Yunus and the central bank have begun rolling out sweeping reforms to stabilise the financial system and rebuild public trust. To begin with, the interim regime has granted greater autonomy to the Bangladesh Bank. The Bank Resolution Ordinance (BRO) 2025, enacted in May, grants the central bank sweeping powers to restructure or close failing institutions, protect depositors, and prevent systemic contagion via bail-ins, bridge banks, and temporary public ownership.

Moreover, under new amendments to the Bangladesh Bank Order, 1972, the central bank governor will now be appointed by the president of Bangladesh and be accountable to the parliament rather than the government. This effectively insulates the president from political pressure.

“The central bank governor is now exercising his independence,” Mustafizur Rahman, quoted earlier, said.

“What he did first was to expose the dirt that had been swept under the carpet. It will take five years to really go back to a healthy situation,” he said, referring to the damage done during Hasina’s years.

Another major reform was the introduction of new loan classification and provisioning rules in September 2024 and April 2025, respectively, which exposed previously concealed debts and forced banks to recognise losses sooner.

In addition, the Risk-Based Supervision (RBS) is set to replace Bangladesh’s traditional compliance audits by January 2026. It will give regulators a forward-looking model to identify vulnerabilities ahead of a spiral.

Yunus’s administration has also revived the ethos of Grameen-style microfinance as a moral and institutional guide. In a landmark move, the interim government cut its stake in Grameen to 10 percent, transferring 90–95 percent ownership to borrower-members—a model of participatory finance that Yunus hopes to scale to other sectors.

One of the most contentious issues is the government’s proposal to remove the legal definition of “willful defaulter”.

The central bank is making a distinction between wilful and non-wilful defaulters in a bid to keep Bangladesh’s business and economy going. Under the proposal, non-wilful defaulters will be allowed to reschedule non-performing loans based on the bank-client relationship. Also, the government will target wilful offenders.

Mustafizur Rahman clarified that the new approach is not about removing accountability but distinguishing between those who defaulted intentionally and those who genuinely could not repay.

“If you are a banker, you know your client. The central bank has allowed banks to negotiate directly with borrowers. If they repay a small portion, say five percent, you can regularise their loans and help them continue business,” he said.

He added that authorities are pursuing “wilful defaulters” who now live abroad, through asset recovery companies and the Anti-Corruption Commission.

“But bringing that money back is a global challenge,” he added.

Despite the reforms, the economy faces challenges.

Private investment has stagnated at roughly 24 percent of GDP for the past five years. High lending rates, part of the IMF-backed contractionary monetary policy, have discouraged borrowing and weakened business confidence.

The capital market and non-bank financial institutions are also in distress, further undermining confidence. Many investors are taking a wait-and-watch approach ahead of national elections expected early next year.

“Investors are apprehensive about whether the elections will take place in February,” Rahman noted. “After the elections, predictability will return and that will help stabilise economic activity.”

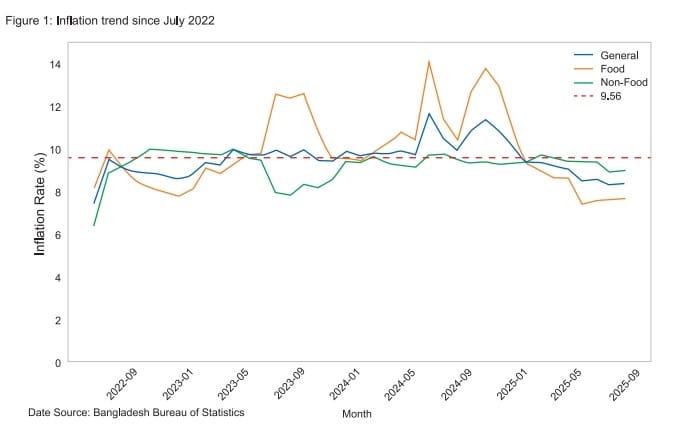

For now, stabilisation appears to be underway. Inflation is falling, the taka has steadied at roughly Tk 122 per dollar, and foreign exchange reserves have risen to over $31 billion, enough to cover more than five months of imports. GDP growth is expected to hover near five percent this year, far below the seven to eight percent highs of the last decade, but better than the contraction many feared.

Although inflation has recently trended downward, it remains above the target level.

According to the country’s Economic Update and Outlook (October 2025), Bangladesh Bank’s tight monetary stance has helped ease inflation, though at the cost of slowing growth. Inflation stabilised at around 8.3 percent between August and September 2025, though the decline in private credit continues to suppress investment and job creation.

The GED warned that record-low private sector credit poses a major risk to future growth and called for policies that stimulate private investment while maintaining inflation control. Deposit growth showed moderate but unstable progress, constrained by high inflation and weak household savings, though remittance inflows and digital cash transfers provided some support.

Analysts warn that if reforms falter, banks could shrink further, capital flight could intensify, and investor confidence could evaporate. Political unrest, like the mass protests that toppled the previous government, could easily resurface.

“To avert bank runs and restore public confidence, Bangladesh Bank has opted not to allow any bank to fail, instead pursuing a policy of bank mergers,” Ashikur Rahman said. “Whether this strategy yields dividends in the medium term will depend critically on how effectively the merger process is designed and implemented, requiring both political will and technocratic discipline from the next government.”

Mustafizur Rahman, however, remains cautiously optimistic.

“The Bangladesh economy is going forward, and the World Bank projection for this fiscal year is about five percent of growth. The taka has stabilised at around Tk 122 per US dollar, foreign reserves have recovered to about $31 billion, and exports and remittances have rebounded modestly,” he said.

“The good steps have been taken, but it will take four to five years to stabilise the financial sector. Any political party that comes next must continue the reforms. Good politics is also good economics,” Rahman added.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Democracy, non-institutional methods of regime change lead to problems—NSA Ajit Doval