New Delhi: Six decades on, the 1965 India-Pakistan war continues to shape India’s strategic thinking. It underscored the need for a strong, credible military to deter adversaries, careful management of the neighbourhood and the understanding that reliance on external support has its limits—lessons once again brought forth post Operation Sindoor.

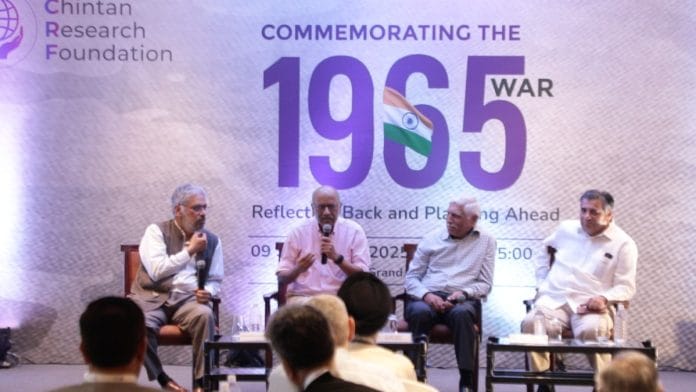

Speaking at a panel discussion at an event commemorating the 1965 war in the Capital Tuesday, moderated by ThePrint’s Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta, former Director General Military Operations (DGMO) Lt Gen Vinod Bhatia (Retd), India’s former High Commissioner to Pakistan T.C.A. Raghavan and foreign policy analyst C. Raja Mohan reflected on key lessons from the 1965 India-Pakistan war.

“Foreign policy rests on hard power,” said Raghavan, arguing that without economic and military strength, international recognition is not enough.

On India’s perceived geopolitical isolation, he said this was overstated. “Nobody is going to get involved when you are fighting in your own region, that’s a given,” he said. While he acknowledged that India today enjoys far more respect internationally than in 1965, he stressed that this should not create illusions about external support in moments of crisis.

The discussion ranged from India’s perceived isolation to the importance of deterrence and the risks of over relying on external powers, drawing connections between the insights of 1965 and the takeaways highlighted by Operation Sindoor.

Turning to Lt Gen Vinod Bhatia (Retd), Gupta asked whether managing India’s neighbourhood involves more than just the Line of Control (LoC) and the Line of Actual Control (LAC). “Definitely much more,” Lt Gen Bhatia (Retd) responded. He argued that India’s neighbourhood policy has often been misunderstood, noting that while New Delhi has intervened in times of crises in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka or the Maldives, it has always pulled back. That, he said, makes clear that India has no expansionist ambitions.

“The neighbourhood is important to us because if the neighbourhood is stable, we are stable,” he said. At the same time, he underlined that strength is essential to credibility, “If we are not economically and militarily strong, our international relations will always be weak.”

Reflecting on the experience of 1965, Bhatia described it as both a “war of mutual incompetence” and a “war of redemption”. India was dependent on foreign aid and militarily underprepared, but the conflict produced a vital takeaway—deterrence is the true guarantor of peace. “Armed forces are not meant to fight wars. We are meant to ensure peace through preparedness, peace through deterrence; conventional, strategic and asymmetric,” he said.

He also discussed how China’s nuclear threat in 1965 spurred India to begin moving towards its own strategic capability, demonstrating that vulnerabilities can be converted into long-term strength.

When the conversation turned to the broader significance of 1965, Raja Mohan highlighted a deeper issue in India’s security thinking—a tendency to rely on external powers or international opinion to resolve disputes.

Asked what this meant for India’s understanding of military power, he used the term “Panipat syndrome,” describing a mindset shaped by history in which outsiders were assumed to decide outcomes. “Dependence on the external world to save us is a problem,” he said. He added that in the 1960s, India missed chances to recalibrate its economy and its relationship with the US, and instead saw its borders with Pakistan hardened into militarised frontiers.

Furthermore, for Raja Mohan, the lesson was as much about mindset as capability. “You can’t simultaneously claim to be the fourth largest economy and the third largest military and yet behave like a victim,” he said. The challenge, he argued, is for India to act like a mature power, taking responsibility for its own security and neighbourhood stability rather than seeking external validation, he further expressed.

This need is as relevant today as it was six decades ago, with Operation Sindoor showing that even with India’s greater standing, the old temptation to see itself as a victim of international pressures has not fully disappeared.

Whereas, former diplomat Raghavan pointed to another continuity which is the danger of assuming that limited military action can yield political advantage. He recalled how Pakistan’s thinking in 1965 had been influenced by the earlier Rann of Kutch conflict, where limited force was followed by international arbitration, producing an outcome that shifted the status quo slightly in their favour.

But he warned that this pattern of “limited force” approach creates a loop in which “tactical moves” substitute for durable solutions. The 1965 war proved such calculations are dangerous, a point that still resonates today.

The panel also reflected on the Cold War context. In 1965, the Soviet Union was not yet a close ally and was supplying military equipment to Pakistan while setting up projects there, illustrating that India could not assume a guaranteed supporter. China, which had gone nuclear in 1964, posed a strategic threat that shaped India’s push for self-reliance in deterrence.

These lessons, the panel emphasised, remain critical—relying on other powers to fight India’s battles is a dangerous illusion.

Furthermore, Lt Gen Bhatia (Retd) also stressed that military preparedness goes beyond numbers and equipment; it requires proper planning, absorption and exploitation of capabilities, he said, adding that India’s experience in 1965 and subsequent conflicts has shown that emergency procurements alone are insufficient and that strategic intelligence, operational coordination and political clarity must complement a strong military.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Lessons for airpower from Operation Sindoor—unified command to tech advancements