New Delhi: What’s the decimation of the feared Russian tanks in Ukraine telling us? Is the tank, along with other armoured fighting vehicles as we’ve known them, headed the same way as the medieval war elephant?

Lately, besides the numerous pictures and videos of burning, exploding or wrecked Russian tanks, we’ve also been witnessing some contrasting sights. Consider these two:

The Tank X drove down a pleasant country lane outside Tallinn, Estonia, this summer, its engine humming like a well-tuned sports car. Soon, its sensors, controlled by artificial intelligence systems, detected a threat and the tank alerted a remote human operator. When the tank got permission to open fire, it trained its Bushmaster 30 mm cannon on the ‘threat’ — a car — and tore it apart. Had a tank crew been on board, they might have felt some satisfaction at the accurate targeting.

Contrast this with a scene from last year. As Indian and Chinese troops facing off on the southern shores of Pangong Tso in Ladakh disengaged, columns of tanks and armoured personnel carriers belched great clouds of smoke into the freezing February air. This, in fact, has been the face of modern war from when Nazi Germany’s armoured columns cut into the Ardennes in 1940.

The decimation of Russian armour in Ukraine — including T-72s and T-90s, which make up more than nine-tenths of the Indian Army’s fleet — has shown that scenes like the one from Pangong Tso might be better suited to a history textbook than the battlefield.

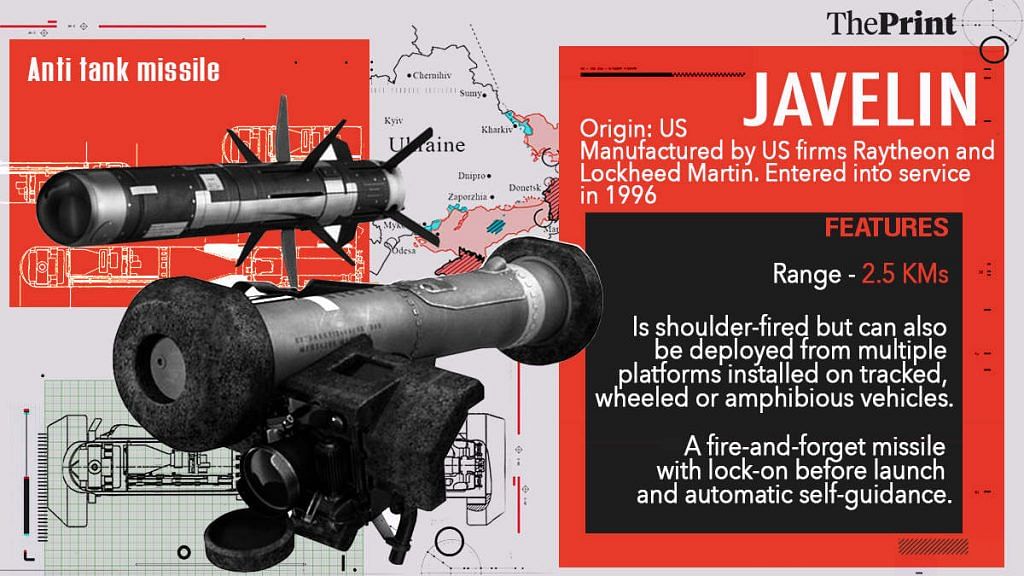

Lightweight, shoulder-fired American-manufactured Javelins, and the Swedish- and British-made New Generation Light Anti-Tank Weapon (NLAW), together with drones, have relentlessly hunted down the king of the battlefield. Over 1,400 Russian tanks are confirmed by independent photographic evidence to have been destroyed, abandoned, or captured — and that’s not counting armoured personnel carriers, infantry combat vehicles, and tracked artillery.

It’s the greatest tank disaster since Israel’s army destroyed the combined forces of Egypt, Syria and Jordan in the Six-Day War of 1967, despite their superior armoured strength.

So, is it the outcome of problems with Russian technology and tactics? Or have tanks themselves become an expensive liability? And what lessons must India draw from new classes of technology as it prepares to fight future wars?

Also read: Why the famed Russian Air Force failed in Ukraine and the vital lessons IAF can draw from it

Why Russia’s tanks failed

Experts are divided on why tanks have, well, tanked in the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

To some, like military analyst Rob Lee, the problem isn’t so much tanks themselves, as mistakes in employment and planning, and the lack of proper infantry support. The contest between tanks and anti-tank systems, he argues, has been constant. For example, the Soviet Union’s Sagger 9M14 Malyutka wire-guided anti-tank missiles blunted Israeli tank supremacy in the 1973 Yom Kippur war.

Learning from the experience, Israel began producing the heavily armoured Merkava —and insurgents in southern Lebanon learned, in turn, to adapt booby-trapped artillery shells to knock out the tank.

Even though Kyiv is knocking out large masses of Russian armour, it’s still seeking more tanks of its own from the West — knowing they’ll be protected by superior artillery like the United States-made HIMARS and other precision munitions, as well as armour that can defeat Moscow’s existing anti-tank missiles.

For radical strategic thinkers, though, the Ukraine war underlines a fundamental shift in warfare driven by technology. The heavy, expensive military platforms that formed the foundations of militaries in the industrial age, Phillips Payson O’Brien argues, are giving way to nimbler, smarter systems. Together with the fighter jet and the warship, he writes, tanks “are being pushed into obsolescence”.

Like many big arguments about warfighting, there’s no simple answer to this debate. Little doubt exists that the commanders in charge of Russia’s T-72, T-80, and T-90 tanks made serious mistakes. Tank columns choked highways, enabling Ukrainian forces to pick them off. Having destroyed the first and last tank in a column, Ukrainian soldiers could pick off the rest at leisure — almost, as it were, with a drink in hand.

The armoured operation was also unleashed in the pre-winter wet season, known as the rasputitsa, when mud makes armoured movement tough. The Russians should have known this, since the Nazi offensive on Moscow in 1941 stalled for just this reason: “General Mud” and “General Winter”, Red Army soldiers used to joke, were their most reliable commanders.

A third of the over 1,400 Russian tanks independently estimated to have been lost were captured or abandoned — a sign that poor logistics left crews without fuel or spares.

To make things worse, the bulk of tanks Russia has deployed in Ukraine were produced in the 1970s and 1980s. Even though they have been modernised with explosive reactive armour, designed to mitigate threats from shoulder-fired missiles, the tanks remain vulnerable to systems with tandem warheads, like the Javelins and NLAWs. Russian tanks are especially vulnerable to missiles which target their turrets from above, because of design flaws in the ways in which their ammunition-loading systems are configured.

Western tanks, like the United States’ Abrams main battle tank, are already being equipped with active protection systems to defeat incoming missiles and fight off drones. Israel’s latest tank, the Merkava 5, includes protection systems capable of fighting off the country’s own state-of-the-art Spike anti-tank missile.

While acknowledging that tanks indeed face an existential threat, serving Indian Army officers and experts in India that ThePrint spoke to believe it’s too early to write them off.

Former mechanised infantry officer Maj. Gen. Yash Mor (Retd) argues that while Western technology has exposed vulnerabilities of Russian-designed tanks, tactical innovation can help. “You will have to have electronic eyes and ears ahead of your forces to detect threats,” Mor says.

Lt Gen. Vinod Bhatia (Retd) concurs. “Armour tactics will obviously have to change,” he says, “but the psychological impact of a tank can’t be wished away.”

To some, though, the problem isn’t the tactics or the weapons Russia used: It is the tank itself.

Reimagining the tank

The AI-powered Type-X Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV) — dubbed Tank X — developed by Estonia-based Milrem Robotics, is just one of many projects worldwide that are bringing artificial intelligence and unmanned technologies to fighting vehicles.

Tanks without crews don’t need heavy armour protection, allowing for gains in mobility and speed. The United States military says it doesn’t know, for certain, what the next generation of its Abrams main battle tank will look like — but there are many experiments underway, involving multiple kinds of sensors, protective systems, and integration with drones.

In tests carried out in California earlier this summer, the United States Defense Advance Research Project Agency established that unmanned off-road vehicles were approaching the capabilities of trained drivers. Testing is also underway of robots that can autonomously protect landing zones, engage enemies ahead of human troops, and sabotage forward airfields.

A technologist involved in the experiments described the new generation of combat technologies as “lightning in a bottle”: “This thing was light, it was agile, and it was lethal.”

Future tanks could also become hubs at the centre of multiple kinds of robotic vehicles, missiles, and airborne platforms. Israel’s Elbit Systems in June this year unveiled one such vehicle that will go into testing next year. An unarmed version of Tank X served with French forces fighting jihadists in Mali, back in 2019.

For some military thinkers, however, endlessly upgrading tanks to cope with new threats seems a pointless enterprise. The tank was designed to defeat a very specific military challenge that emerged at the dawn of the industrial era — the machine gun. Post-industrial technology offers new means to do what the tank does, but cheaper and better.

The United States Marine Corps is simply dumping its tanks, replacing them with lightweight high-technology equipment, such as more drones and precision-guided missiles, even though the US Army still believes in tanks. That radical approach, though, is a step too far for most forces in the West — leave alone India.

The future of India’s tanks

Led by Gen. Krishnaswami Sundarji, the Indian Army began planning in the mid-1980s for wars where fast-moving armoured formations would cut deep into Pakistan. Gen. Sundarji’s war planning was the result of painful lessons learned in past wars.

But even though the great India-Pakistan tank battles of 1965 are celebrated, their outcomes were less than decisive, Amarinder Singh and Tajindar Shergill have shown.

Singh and Shergill are sharply critical of some Indian commanders who, they claim, operated without focus, like “a fire brigade that heard of imaginary fires here, there and everywhere”. Former Pakistani military officer Agha Amin’s history of India-Pakistan armoured engagements also has also shown that they yielded stalemates, not breakthroughs.

The vulnerabilities of its largely Russian fleet now shown up in stark relief, should India invest in more or better? Or explore the possibilities offered by new technologies?

In the short term, the Army is seeking to address its most pressing gap — unmanned aerial vehicles. Two sets of swarm drones were acquired by the Armoured Corps and the Mechanised Infantry in August this year. The AI-based recognition systems in these drones enable them to autonomously recognise targets like tanks, guns, vehicles, and humans. The information is relayed back to a control station, where human operators can order appropriate responses.

Like other militaries, however, the Indian Army is also rethinking what the armoured warfare of the future might look like. It is committed to acquiring 1,700 Future-Ready Combat Vehicles (FCRVs) — a new platform that will be able to engage with the large tank fleets of both China and Pakistan. Among other things, FRCV planners are considering a turret-less tank that is integrated with its own drone swarms and anti-drone electronics.

The Army has also launched Project Zorawar to develop a light tank weighing 25 tonnes or less that can operate in the Himalayas. The Zorawar, like the FRCV, will be empowered with artificial intelligence systems, as well as integrated with drones.

FRCVs are scheduled for induction in 2030 — an ambitious target, given that the Army is yet to even finalise exactly what it wants. Even if the Army makes a conceptual decision tomorrow, seven years is a short time to design, test, and manufacture the FRCV.

The prototype of the Arjun main battle tank — which even today remains controversial, because of its weight and a slew of other technology issues — was first revealed in 1985. The production version Arjun 1A, though, was only cleared for induction into the Army in 2018.

Even more fundamental than the question of what kinds of tanks India will need, then, is the kinds of wars India might fight.

“A single anti-tank guided missile can hold back an entire regiment of tanks in a narrow Himalayan pass,” notes Lt Gen. D.S. Hooda (Retd), former commander of the Army’s Northern Command.

In the decades since the India-Pakistan wars of 1965 and 1971, the plains where tank battles were fought have become densely built up, with villages growing into towns and cities. That means there will be limited room for armoured manoeuvre — and that large-scale artillery bombardments could have unacceptable human costs for both countries.

“From the Chenab River down to Ganganagar, the urban build has become incredibly thick,” says Lt Gen. Rakesh Sharma (Retd), former Corps Commander of the Leh-based 14 Corps. “One would have to flatten entire cities with artillery barrages to allow tank formations to move forward. The human geography of the battlefield is not what it was 30 years ago.”

Each age creates its own weapons. The tank was designed as a response to specific challenges that emerged in the late 19th century. The machine gun had mired troops in trench warfare, and the tank was created to make wars of manoeuvre possible again. Together with the battleship and the bomber, the tank might face its final defeat at the hands of post-industrial technology.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also read: ‘Global interest in India-modified M4’ — South African defence firm wants to manufacture in India