Chennai: On a sultry Monday evening, the platforms of MGR Chennai Central Railway Station were crowded with groups of men from Tiruppur’s hosiery export hub carrying back bags, trolley balls, and rolled-up beds. The 50 per cent tariffs on Indian exports are already driving them out of their dream job. They are now heading back to their homes in Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh on the Ganga Kaveri Express.

Orders have dried up, inventories are piling up, and factory owners can’t pay their idle labourers anymore. Migrant workers are the first to be ejected from the cut-throat price-sensitive export industry—nearly a month before Diwali festivities. Nearly half of the migrant workers have lost their jobs, according to one industry estimate.

“I used to get six days of work every week. Now I barely get two,” said Kuldeep, a worker from Samastipur, Bihar, holding his trolley bag.

“Even on the days we go, there is not enough work to keep us busy. Rent and food cost more than what we earn nowadays. So, it’s better to go home until things improve in Tiruppur,” he added.

His only hope is that he can return to the job when the Trump and Modi governments iron out the trade deal in a way that doesn’t break the industry.

As the Ganga Kaveri Express pulled out of Chennai Central, the men on board carried not just bags, but disappointment and doubts about survival. While some were eager to return once the industry bounced back, others weren’t so sure.

I wanted my daughter to study in an English-medium school in Tiruppur. Now, we will go back to the village. She has to shift to a government school.

Dhileepkumar, textile worker from Bihar

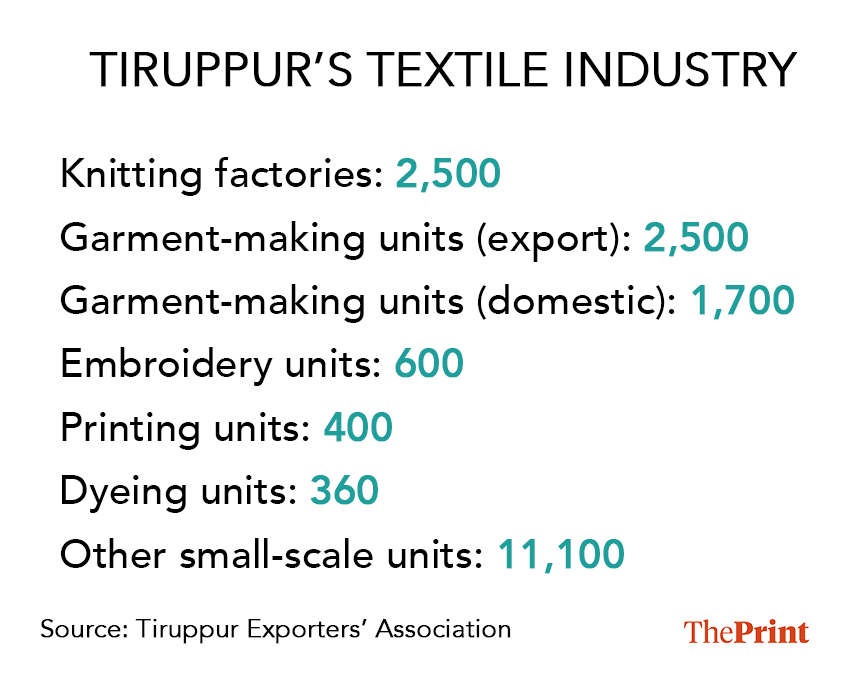

The Tiruppur textile industry, which supplies one-third of India’s textile exports, has been suffering since the tariffs came into effect. Of the 2,500 export knitwear industries in Tiruppur, about 20 per cent have shut down and half have scaled down operations, said A Sakthivel, the founder and honorary chairman of the Tiruppur Exporters’ Association (TEA).

A group of tailors from Jharkhand, who had been working in Tiruppur for about seven years now, echoed Kuldeep’s story.

“We came here with dreams, built a small life, but everything is collapsing now. The owners say they don’t have enough orders to give us work. What will we do sitting idle?” said Pathan Kumar, a tailor from Jharkhand.

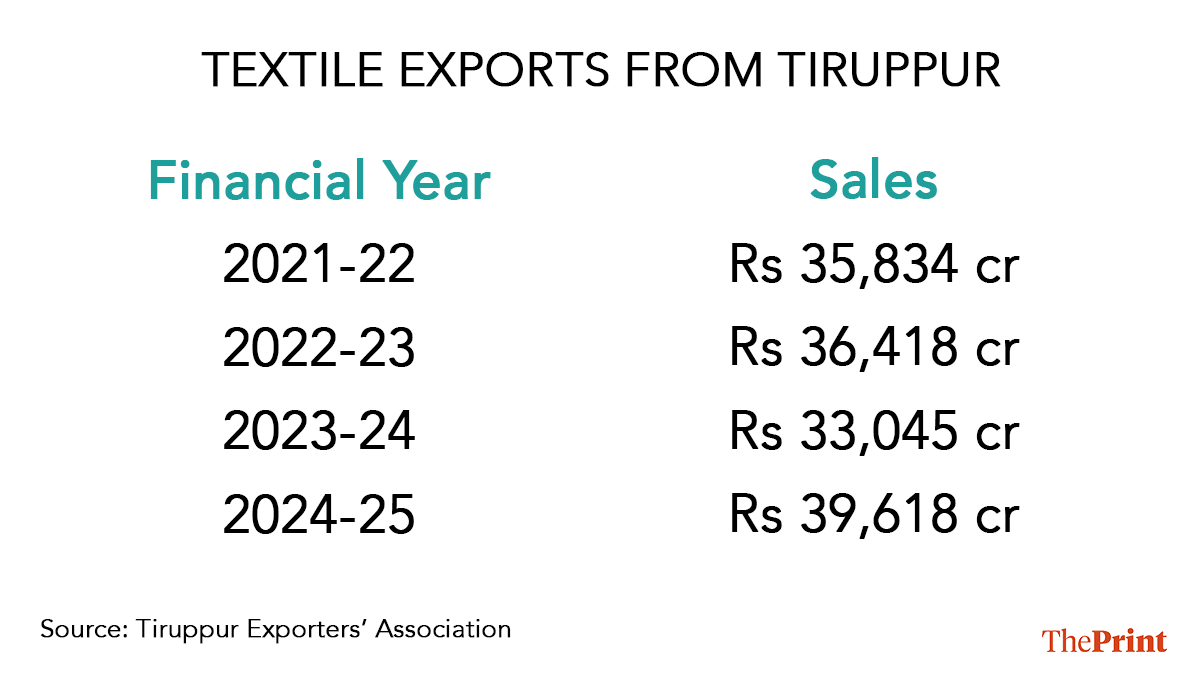

The United States remains Tiruppur’s largest export market. The city accounts for nearly 90 per cent of India’s cotton knitwear exports and about 55 per cent of overall knitwear exports, according to the Tiruppur Exporters’ Association (TEA). In 2024-25, exports from Tiruppur touched Rs 39,618 crore. Of this, an estimated 30 to 35 per cent was shipped to the US.

Employers admit that they are not able to sustain operations with a lower number of orders.

“Our total volume of business has fallen by almost 40 per cent. Customers in the US have almost stopped their orders, and without demand, factories cannot run at full capacity,” said S Krishnamoorthy, who owns a medium-sized unit in Karumathampatti in Tiruppur district.

According to the TEA, of the 2,500 export garment-making units, about 50 per cent have laid off half their manpower.

“The crisis is real, and some exporters are forced to shut their additional units, as they could not supply to their US customers with the increased tariff,” Sakthivel said.

For migrant workers, it means a choice between fewer days of work with lower wages or leaving the city in search of survival.

Many workers said that the crisis was more or less the same as that during Covid-19.

“However, this time, we are lucky enough to have public transportation and enough money to get back to our homes,” Kuldeep said.

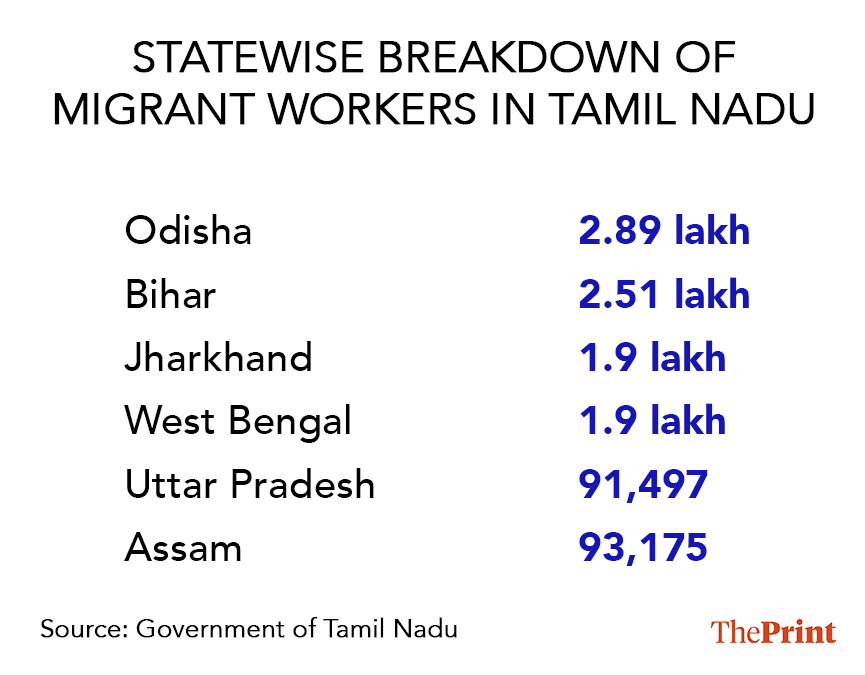

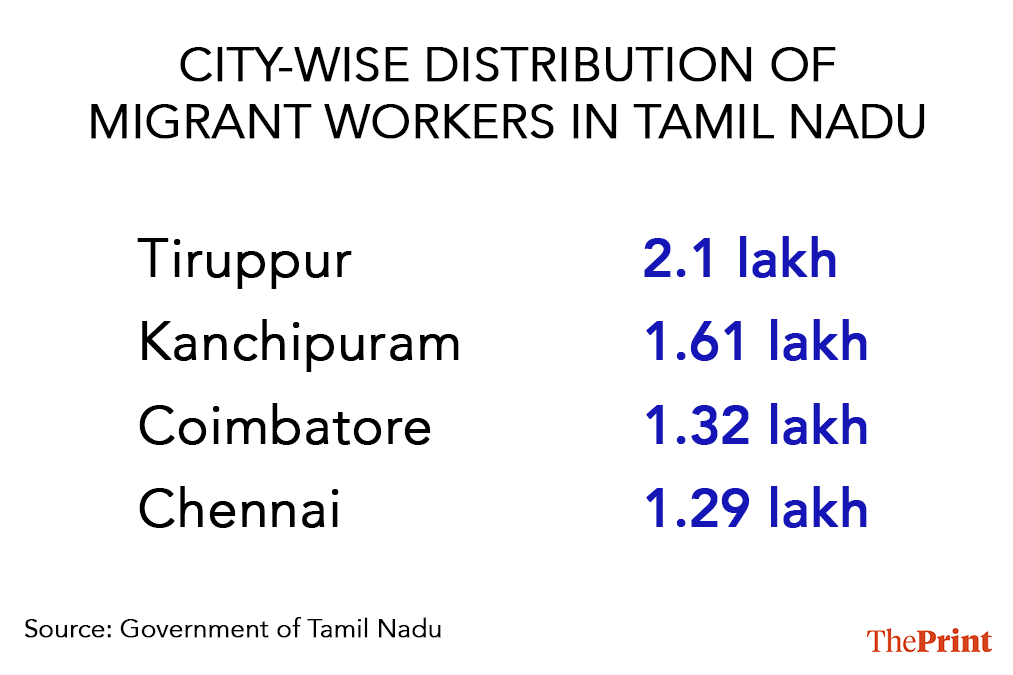

According to data from the state government, there are 2.1 lakh registered migrant workers in Tiruppur district, the highest in the state. Labour unions, however, said that the actual number would be close to 3 lakh.

G Sampath, district general secretary of Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), said that of the 5 lakh workers in Tiruppur, more than half come from Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh.

“They handle much of the work, including stitching, ironing, and packing the garments, while locals are deployed in supervisory roles. When orders stop, these migrants are the first to feel the heat,” Sampath said.

Mass exodus

At Chennai Central, as the Ganga Kaveri Express prepared to leave, many workers spoke about their dream of building their lives in Tiruppur.

“I wanted my daughter to study in an English-medium school in Tiruppur. Now, we will go back to the village. She has to shift to a government school,” said Dhileepkumar from Bihar, who has two daughters.

Some are worried about debts and finding a job in their native place.

“I borrowed Rs 50,000 to buy a bike and send money home. Now, I don’t know how to repay the money,” said 24-year-old Vikram Singh from Uttar Pradesh.

There were few women in the crowd. Nanditha Devi, who was holding her toddler, said that her dream of making a peaceful life has once again hit a roadblock.

“I thought Tiruppur would give us a stable income and a peaceful life. But it has become impossible now, and we were again made to run from pillar to post to get a job and get a two-square meal,” Nanditha said.

It is not just the industry at stake, but lakhs of families dependent on these wages. If workers return home permanently, it will take years to rebuild the labour base.

G Sampath, district general secretary, CITU

The ones who stay back must adapt by finding jobs outside the garment sector. Some have taken up construction, and others have moved to different cities.

A manpower agency owner, R Santhosh Kumar, said that he is no longer able to send migrant workers to the existing textile units since everyone is reducing production.

“Even today, I sent 50 people from Bihar back to their hometowns. Some of them wanted to get a job somewhere, so I am sending them to Chennai and Coimbatore to find a job in the construction sector,” Santhosh Kumar said.

According to the manpower agencies, while the migrant workers in their 40s tend to return home, those in their 20s and 30s are looking for alternate jobs in Chennai and Coimbatore.

One such case is Atheep, a 27-year-old textile worker from Uttar Pradesh, who left Tiruppur a week ago and managed to find a painting job at a construction site in Chennai. However, the pay and working conditions are far from ideal.

“I would get anywhere between Rs 700–900 per day in Tiruppur. But the pay for painting is less since I am new to the field. I think it’s better to return to my native place along with my villagers instead of struggling in a new field and new place,” Atheep said.

Labour unions say that Atheep’s story is not an isolated one, but a part of a wider exodus that reflects how vulnerable migrant lives are when steady jobs vanish.

Exporters and associations warn of long-term consequences if relief doesn’t come soon. The TEA estimates that nearly 20 per cent of jobs could vanish if the situation persists.

“These workers don’t have savings. They live in rented rooms, and every week without work, their debt increases. That is why you now see trains out of Chennai and Tiruppur packed with workers heading to their native places,” Sampath said.

We are taking small orders just to keep the machines running, but this is not sustainable. Every unsold piece is a liability, and the stocks are piling up.

S Krishnamoorthy, small unit owner

Unions have demanded immediate action from both the state and the Centre. They want wage support for workers, electricity subsidies for industries, and negotiations with the US.

“It is not just the industry at stake, but lakhs of families dependent on these wages. If workers return home permanently, it will take years to rebuild the labour base,” Sampath added.

Also read: Belagavi to Boeing. Karnataka aerospace hub is a shining postcard for Make in India

Production downsized

In the Palladam belt, two of five factories under the RRK group have shut. Nearly half of its 2,000 workers have been laid off.

Jayakumar, general manager at RRK group, said that the company is coping with domestic orders and export orders from countries besides the US.

“But for those limited orders, we cannot run all the units with full manpower. Hence, we were forced to shut two units and reduce the production in the three units, which are still operational,” Jayakumar said.

Small–scale unit owners like S Krishnamoorthy are running far below their full capacity.

“We are taking small orders just to keep the machines running, but this is not sustainable. Every unsold piece is a liability, and the stocks are piling up,” he said.

Competitors from Bangladesh and Vietnam, who enjoy much lower tariff, are likely to take over the contracts that were once received by Tiruppur exporters.

KM Subramaniam, President, TEA

Supporting industries like dyeing units, tailoring units, transport, and traders are equally hit. “I used to supply buttons to three factories. Now only one calls me, and that too, once in a while,” said M Ramachandran, a small-scale supplier in Tiruppur.

Exporters and associations warn of long-term consequences if relief doesn’t come soon. The TEA estimates that nearly 20 per cent of jobs could vanish if the situation persists.

“Half of Tiruppur’s workforce is made up of migrants. They are the most vulnerable when orders dip. If the tariff is not rolled back, or if there is no government support, we risk losing not just workers but also our hard-earned export markets,” said TEA President KM Subramaniam.

TEA estimates an annual loss of Rs 14,000 crore if the crisis is not resolved soon.

“Competitors from Bangladesh and Vietnam, who enjoy much lower tariff, are likely to take over the contracts that were once received by Tiruppur exporters,” Subramaniam said.

Nevertheless, the exporters are hopeful that the situation will return to normal since the two countries are in talks.

Some exporters said that enquiries from American buyers have resumed ever since the two governments started talks, but the quantity of orders remains uncertain.

“We are hopeful that we will soon get the orders, but unless tariffs are addressed, enquiries alone cannot save us,” said Raja Shanmugasundaram, a member of TEA.

According to Shanmugasundaram, the crisis feels deeper than the Covid-19 lockdown.

“During Covid, at least we knew demand would return once the lockdown ended. Now we don’t know when our market will come back.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

First tamizhans are not Dravidians… Hindi population must come from 75 cr to 40 cr if india wants to survive.. Nonsense hindiwala usjng name of india and ruining souths land language culture money.. Where local people will go..state visa permit must enable for these guys..bjp pushjng hindi people to south.. Santhanis takes advantage here to bring vedic and Sanskrit all over south..

The Dravidian people of Tamil Nadu must thank President Trump for helping them to get rid of the Aryan invaders/outsiders from UP, Bihar and other parts of India.

Maybe they can include President Trump in the pantheon of leaders like Periyar who saved them from the Aryans. Erecting temples in his honour would be a good way to express gratitude.