Jaipur/New Delhi: A Delhi-bound truck loaded with ripe bananas pierces through the dead of the night on the newly built Delhi-Mumbai Expressway. Gaffar, the driver, yawns infectiously on this long open stretch. It’s nothing like the cacophony and traffic of the old highway, which requires a driver to constantly juggle between clutch, brake, and accelerator—in a way keeping him alert. All that is a thing of the past. On the smooth new highway, Gaffar flirts with nothing but the accelerator.

“The expressway has reduced my travel time significantly, but with nothing but darkness on the road, and no traffic, I feel really sleepy,” the 30-year-old driver said.

A native of Alwar, Gaffar has been transporting goods across north Indian cities for 15 years now. He is a ‘khandaani’ truck driver. Almost everyone in his village drives a truck. He was just 13 when he started his career—first as an assistant to a driver, transporting marbles, then getting his own license at the age of 19. Drivers like Gaffar are charioteers of the humble yet dominating trucks that rule the highways and expressways after nightfall.

The high-speed expressways that India has built over the past 15 years are shaping the lives of the humble truckers. The new roads dotted with glass-fronted joints that sell burgers and fries symbolise aspirational India and a reminder for truckers who spend long hours on these stretches that their world has changed. They must adjust to new realities. The highways with traffic, chai tapris, thekas, dhabas, and the familiar faces are now in their rear view mirror. They are left a little lonely, in the company of nothing but long stretches of perfectly pitched tarmac that’s a little less humane. And trucks have donned a new avatar. Decorated dashboards with loud, musical honks are now fading into obscurity. From artsy trucks, it’s a shift to corporate carriers with little space for the jagmag lights. From harassing police on the roads to smooth highways with no space to stall their journeys, truckers are both skeptical and enthusiastic. It’s a cultural transition from colour and chaos to efficiency and uniformity.

“We used to encounter dacoits and thugs, and every journey used to be a gamble on our lives. One wrong move and the truck could skid off the road. Things have changed drastically now,” a truck driver said.

Expressways are the picture-perfect postcard for the dream of Viksit Bharat. The government claims that the national highway network increased by 60 per cent between 2014 and 2024, and that high-speed corridors have increased from 93 km to 2,400 km. Their construction is glamourised and valorised as unprecedented successes at political rallies and investment summits. And yet, infrastructure for truck drivers, who spend the most time traversing these highways, is lacking.

So far, expressways cover close to 3,000 km of roads in India, with the ambitious goal of covering 50,000 km is on the cards. The government wants to reduce the travel time of trucks and carriages to make road transport safer and more accessible. And the drivers feel the change.

“If there were no expressways, then congestion would have been mindboggling. Run time efficiency has increased. Trucks are faster and safer. But load availability is still low, and mileage isn’t improving. So the overall average has not changed,” Pradeep Singhal, chairman of All India Transport Welfare Association, said.

A safer drive

In Rajasthan’s Shahpura, a bunch of truckers sit and chat over a cup of tea. Some are washing their clothes, others getting a shave at the dhaba’s roadside barber shop.

Girdhari Lal Gujjar, a 55-year-old trucker from Rajasthan, takes the others down memory lane. A time when they used to travel in groups of four trucks, across narrow one-way roads, sleeping at night in the jungles.

“We used to encounter dacoits and thugs, and every journey used to be a gamble on our lives. One wrong move and the truck could skid off the road. There were no places to eat for miles and miles. Things have changed drastically now,” he said.

Drivers often misuse this freedom of fast expressways by placing a brick on the accelerator to give their feet some rest. Many are even drunk while driving.

Gaffar—who is much younger—has always driven through highways with sparse traffic, sleeping in his truck in private parking spaces run by villagers and dhaba owners.

Despite Gaffar’s brief trucking career, the 30-year-old is not untouched by the recent shift. That’s how rapidly India has built the expressways.

Gaffar spends his days and nights transporting goods on the Delhi-Mumbai route. He has no record of the numerous trips he has undertaken, but can recognise the trees by the side of the road.

He now has a brand new route under his wheels, in his five-year-old truck. And he couldn’t be more excited. Patches of the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway stretch across six states. The Sohna- Rajasthan’s Dausa stretch was inaugurated by PM Modi in 2023.

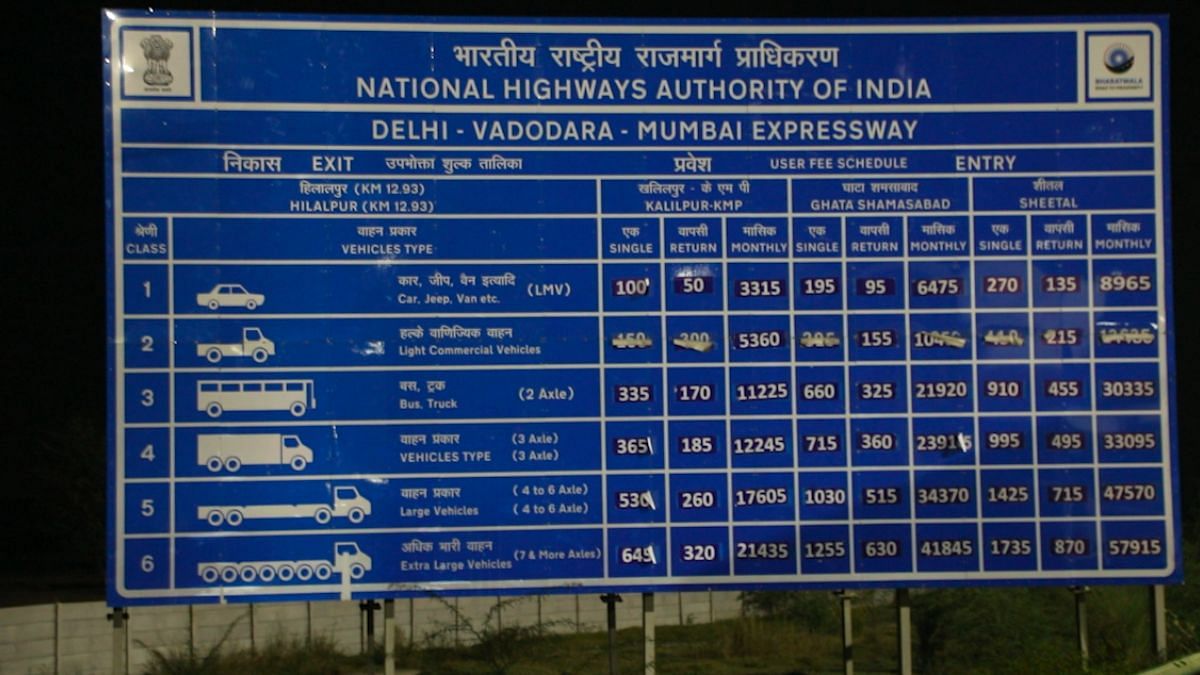

“We’re certainly getting better mileage, and better roads are leading to cost reduction. However, the exceedingly high tolls nullify these cost savings,” said Pradeep Singhal, chairman of All India Transport Welfare Association, said.

The new expressway has reduced his travel time between Jaipur and Delhi by at least two hours, as he cruises on a smoother and more fuel-efficient route. It and is also good for his back—the bumpy highways in an ever-rough truck journey are bad news for the spine.

ThePrint was on board Gaffar’s truck as he told the story of a transforming highway landscape while driving on the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway through a sandstorm.

He has no romantic feelings left for the old highway or the friendships he made there. That path was full of roadblocks. For a trucker, it was like being inside a video game — full of villains to defeat and barriers to overcome.

The first barrier in Gaffar’s way was the ever-present police or regional transport office (RTO) officials, who he claimed would ask for bribes even if all his paperwork was in order.

“The police had really made this job difficult. But the expressway is good, out of the reach of officials who are out to harass us. They cannot stand on this fast road. And thank god for the cameras constantly surveilling the babus!” he cheered.

If RTO officials weren’t scary enough, the drivers have had a hard time dealing with dangerous cow vigilantes, eager to stop Mewati trucks, and extorting money for safe passage. Expressways are clear of such thugs, too.

“They (cow vigilantes) try to get on the Delhi-Mumbai expressway, and sometimes block the exit near Alwar or Nuh,” he said.

Smooth roads with long uninterrupted stretches mean they can go on for miles, do high speeds without having to worry about decelerating. Drivers often misuse this freedom by placing a brick on the accelerator to give their feet some rest. Many are even drunk while driving.

Expressways are also generally better for a truck’s health, reducing maintenance costs and returning higher miles per gallon. But for now, transporters haven’t seen these returns on the Delhi-Mumbai expressway, not fully functional yet.

“We’re certainly getting better mileage, and better roads are leading to cost reduction of spare parts of the trucks as well as other maintenance costs. However, the exceedingly high tolls nullify these cost savings,” said Pradeep Singhal.

Also read: These Bihari sisters don’t just speak fluent Tamil—use Chennai slang, draw kolams at home

Empty roads

The swanky, sanitised expressway that wears urbanism on its sleeves passes through rural India. And it is the people of these villages who cater to the needs of the truck drivers, offering pocket-friendly meals.

Around 2 am, Gaffar’s eyes were getting heavier with sleep. To stay alert, he tuned SR 4000 by Aslam Singer, a popular local artist of the region. But that didn’t work. A cup of kadak chai or Coca-Cola might do the trick. But there are no outlets on the desolate long stretches of the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway, frustrating him.

A romantic at heart, Gaffar’s truck is decorated with red heart motifs and colourful tassels. On the windshield, he has painted the Taj Mahal—another symbol of love. He got these done from roadside vendors in the Azaadpur mandi for Rs 500.

Roadside dhabas with affordable food light up the sides of India’s old highways, where drivers used to take a break from their journeys. The infrastructure of expressways is far more sanitised. A McDonald’s or a Starbucks is of no use to a truck driver. Eateries don’t have the menu drivers want. And at some of these places, drivers are not even allowed entry. And so, Gaffar and his colleagues have to wait 100 km to get their nicotine dose.

The National Highway Authority of India has planned 270 wayside facilities across the country, of which 94 have been planned on the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway. These facilities will also have designated spaces for truckers. An additional 376 facilities have been planned for greenways and expressways.

Even though truck drivers currently lament the absence of facilities to bathe, park, and sleep on the expressway, the infrastructure is a work in progress. For now, most truckers park their vehicles in private parking spaces for Rs 50-100 a night and sleep inside the trucks. On the expressways, the government is planning to set up dormitories for the travelling truckers.

At a rest stop near Dausa in Rajasthan on the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway lies dhaba 29, hidden from the glamorous food chains at the front. It’s a designated space for drivers. But the prices don’t reflect that. Tea rates are missing from the menu, and multiple truckers said it’s charged at Rs 40—a small detail that instantly alienates them.

The swanky, sanitised expressway that wears urbanism on its sleeves passes through rural India. And it is the people of these villages who cater to the needs of the truck drivers, offering pocket-friendly meals. They come to their rescue.

Drivers park their trucks on the side of the roads and hop out of the expressway, and make their way to dhabas that villagers have opened up on their fields. Here, truckers feel at home.

“The only thing missing here is seating arrangement!” one of them exclaimed.

Gaffar, with a glass of Mountain Dew in his hands, knows this joy is fleeting. “Once the expressway is completed, these dhabas will be removed. And we’ll be left with the Rs 40 chai,” he said matter-of-factly.

“It is not required to have a dhaba every 2 kilometres, but the government is creating facilities every 50-100 kilometres,” said Singhal.

The truckers and the dhaba people share a bond. But the drivers can see that the end of the old highway culture is nearing, and with that, these familiar ties.

“They (dhabawallas) sometimes give us food for free, or if we call them for help, they send a mechanic and don’t charge a lot of money. We can’t take them with us to the new roads, and the dwindling guests at this dhaba are crushing our hearts too, as if we’re losing our own business,” said a driver.

Truckers may have found ways to sneak out of the monotonous expressway and have a slice of their old ways, but they can’t escape the toll gates. Despite a FASTag system in place, they complain of long snarls at many points. And it extracts huge costs compared to the old highways.

Between Mumbai and Delhi, Gaffar paid Rs 5,500 in toll. But truckers have made peace with it, focusing more on what expressways give in return.

“The toll is high but it’s fine… for such a good road will have to pay the toll tax right,” Gaffar said.

The old single-lane highways added to the maintenance cost of the truck and were also difficult to drive through, as high beams from oncoming traffic could nearly blind a person, and driving through villages used to be tricky. Gaffar remembers when the Delhi-Gujarat route was a single-line stretch; now it’s a four-lane expressway. He’s watched these transformations unfold over the last two decades.

“Toll has become a revenue infrastructure model, this is a huge expense. After diesel, our highest expense is toll, and the entire transport business is all about margins. Because of the high toll, we’re unable to avail full benefits of fuel efficiency,” Singhal said.

Dying old highway

In the blockbuster Disney movie Cars, the protagonist car, Lightning McQueen, stumbles upon a deserted old town, which was once a thriving street on the highway. The town loses business once an expressway comes up. The business cars of this old town light up their shops every night, waiting for passersby, who never come.

Decades-old dhabas on highways are facing a similar situation.

It’s midnight. Moolchand, 60, who has been working at the Radhe Radhe roadside dhaba for the last 35 years, desperately tries to stop vehicles, inviting them into the parking. His eyes are red and teary. The restaurant lies empty, not a customer in sight. He has seen better days.

This dhaba has been a popular resting stop on the Delhi-Jaipur highway for over three decades and has enjoyed constant crowds and revenue. But things changed last year.

“The traffic of Marutis has significantly decreased,” said Sahil Sharma, the proprietor, about small cars choosing to cruise through the new expressway instead of the highway.

“They never could finish this highway; it always has traffic jams, especially near Bilaspur, because some patch or bridge of the road is always under construction. Now, they’ve built the expressway!” said Sharma with a defeated tone.

Most passengers tell him they now avoid the highway because of the constant traffic jams. Over the past year, Sharma has watched dhaba after dhaba shut shop along the route.

“Earlier, we would get passengers driving to Jaipur, Punjab, even Gujarat, but now only people going to Khatushyamji temple, or Salasar Balaji temple, are choosing this route. It has significantly affected the business,” Sharma said.

Stories of a shrinking business were echoed by restaurant owners and shopkeepers lining the highway—on the Delhi-Jaipur Highway, as well as NH 48 crossing Nuh.

Most of the trucks choosing this old road are the ones that shuttle between Rajasthan and Delhi. Transporters say they make this choice to avoid high expressway tolls. The ones going toward Gujarat or Maharashtra avoid it completely.

Anil Pathak, a young driver, is one of them. Om Logistics, the transport company he works for, asks him to take the old highway to avoid tolls.

On the bumpy road, Pathak’s truck rattles as he navigates the traffic jam. His feet hardly get to touch the accelerator, it is more of a clutch-break, clutch-break situation.

Unlike Gaffar’s, Pathak’s truck is devoid of character. It doesn’t have art on it or tassels hanging from its body. He simply has an Om Logistics logo in blue painted on the vehicle.

All-India permit trucks are required to have a uniform colour, and the culture of decking up the vehicle is more prevalent in Punjab. Most trucks have the ‘beti bachao, beti padhao’ slogan on their rear. Madhya Pradesh even encouraged painting this slogan on truck backs. Indian trucks are feminist in nature, at least in the messaging they carry as they barrel down the highways.

Twenty-five-year-old Pathak from Mainpuri in Uttar Pradesh sleeps in trucks. A Shiva idol sits on his dashboard. He honks in front of every temple he passes in reverence. It’s midnight and the temperature is still hovering at 31 degrees.

The heat of the engine, which is directly under the driver’s seat, coupled with the soaring temperatures, discourages him from driving during the day. So he’s used to being a night owl.

Pathak wanted to be a soldier. But failing that, he chose to drive the truck, a profession he believes is as essential as being in the Army.

“If we weren’t here to supply goods from one end of the country to another, you all would suffer a lot. Isn’t it?” he said.

He enjoys the cacophony of the old highway. Driving through it doesn’t make him feel lonely.

There are chai points where truckers often stop for a quick smoke and a chat. Dhabas are where they have made friends and always find a buddy to say hello to. In case the truck breaks down, there are mechanics available who can fix the vehicle without burning a hole in their pocket.

Shops meant for drivers that sell small coolers, fans, stereos, engine oil, and other gadgets dot the old highway. Boom boxes placed in them blare songs at a pitch that can lead to hearing loss, but not many pull over at their shops now. The items keeping their businesses floating are refreshments such as cold drinks, wafers, and tobacco.

“Earlier, I used to make at least Rs 3,000 every day, now it is not even Rs 1,500 a day,” Pramod Kumar, a shopkeeper, said. A Haryana resident, he is a seasonal DJ. He said winters are anyway slow for business, so he shifts to amp up wedding celebrations in his neighbourhood instead. But this time, he will probably have to shut shop for good.

Also read: Delhi-Mumbai Expressway is impressive but Indians’ driving lanes apart

Changing villages

Master Javed Khan, a teacher for over a decade, has opened a school in the farms of Golpuri village in Nuh district, right alongside the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway. The new building came up after a portion of his land was acquired for the construction of the Expressway. He got Rs 66 lakh as compensation against an acre of land.

“We were all really happy and celebrated when the expressway was proposed. We received good money for the land acquired and opened businesses with that money, but the way the construction has happened…. we have had some bad experiences,” Khan said.

The highway cuts through the agricultural lands of the village, which has made cultivating fields across the road unviable for the villagers. Passing vehicles fling trash into their farms.

“The wall they built here to separate us from the Expressway is already broken. We risk our lives by crossing the expressway. We were given no crossing from underneath the bridge. We are left with no choice,” Khan added.

The villagers complained that their fields have become uncultivable because there is no way for them to take their tractors across the expressway.

Golpuri also has a huge population of truck drivers who take a 10 km detour on the expressway to reach their homes. The planners didn’t provide an exit near their village.

The villagers also complain of waterlogging in their fields. Water from the expressway collects on the farmland, making farming difficult.

Villages in the Mewat region along the Expressway are losing both business and a good night’s sleep.

“We used to get 200-250 trucks in our parking every day, but now barely 100 trucks are parked here every day. The expressway has completely eaten into our business,” Mohd Sabir, who runs a truck parking and eatery just under the Delhi-Mumbai Expressway at Nuh, said.

Ahead on the highway toward Alwar, the businesses are now sustaining on orders from nearby towns and villages. There is a 70 per cent decline, multiple dhaba owners say, in their orders since the Expressway came up.

One resident of Nuh, Javed, even opened an eatery on the highway after his land was acquired for the expressway. But the very project that made his business possible is now making it harder to keep it running.

Drivers talk of huge changes in how they operate today. Old truckers recall a wilder India—single-lane roads cutting through dense forests, surprise encounters with tigers and leopards, and the constant threat of highway goons that forced them to carry weapons for protection. The Indian highway has come a long way since those days, but there is one thing truckers say still eludes them: respect.

“The driver line is useless, I came into this profession following my father’s footsteps,” Farooq, a 25-year-old driver, said, “But all we want right now is the toll to be decreased and a little bit of respect on the road.” His older colleague, Gaffar, though, is much more accepting of changes. At least he is safer now.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Trucks on the right lane and drivers on mobile phones

Another Gandhi family inspired writer.

Great article, well done.

Nice article. I missed the ‘lorry’. It is not Rs but ₹. The picture of the lorry sporting a feminist logo inadvertently shows the registration number, it should have been blurred.