Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

For centuries, women have been integral to the world of espionage, though often relegated to roles that are both limited and stereotyped. Throughout history, the contributions of female spies have been overshadowed by cultural narratives that cast them as either seductresses or morally compromised figures. This article delves into the historical roles of women in espionage, shifts in how they are perceived, and the barriers they continue to face in achieving equality within intelligence services.

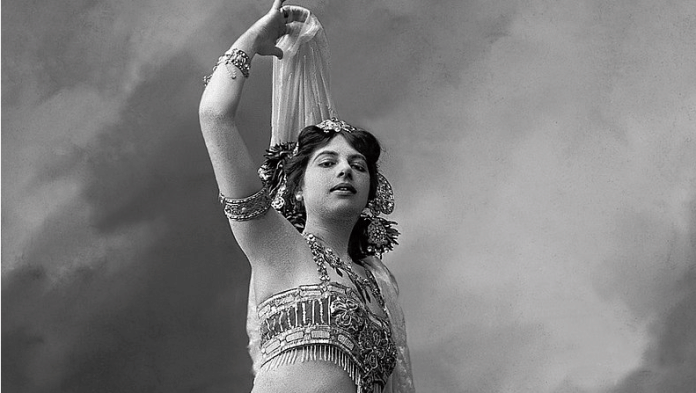

Public perceptions of female spies have long been shaped by the “femme fatale” archetype, as seen in the infamous example of Mata Hari. Known as the “exotic dancer turned spy,” Mata Hari was a Dutch national who gathered intelligence for Germany during World War I by leveraging her relationships with high-ranking Allied officers. Captured and executed by the French in 1917, she became a cultural symbol of seduction and deception. This perception reflects what sociologist Patricia Hill Collins describes as a “controlling image”—a lens through which women in espionage are seen as morally dubious, exotic, and, above all, dangerous.

Historically, society has regarded women’s bodies both as a tool and a liability within espionage. Due to cultural biases, male spies often viewed women as less of a threat, allowing female agents to operate with relative ease in male-dominated spaces. However, the same qualities that made them invaluable were seen as compromising; the “femme fatale” label imposed a double standard that questioned their dedication and professionalism. Despite the perceived advantages of their appearance and social skills, women in espionage were rarely given the recognition they deserved, and their roles were often minimized to supporting actors.

Despite the persistence of stereotypes, female agents have consistently proven their capabilities in intelligence-gathering roles. During World War II, women were instrumental in breaking codes, deciphering enemy plans, and working on projects like the Enigma codebreakers at Bletchley Park. These roles required keen analytical skills and an ability to interpret subtle patterns—traits that have proven invaluable in intelligence work. Women’s success in these areas stems in part from the nature of intelligence itself, which values discretion and subtlety over physical prowess or overt displays of power. Intelligence work, with its emphasis on analysis, deception, and intuition, has often suited women better than other national security roles that prioritize traditionally “masculine” qualities like physical strength and combat experience.

However, one tactic that has continued to reinforce the “femme fatale” stereotype is the use of sexual entrapment, or “honey trapping.” This technique involves using seduction to lure male targets into compromising positions or extracting information. Unlike male spies, who may establish long-term relationships to earn a target’s trust, female agents are frequently stereotyped as relying on their physical appeal. This perception reinforces the notion that women use charm rather than conventional intelligence-gathering methods to achieve their ends. “Honey trapping” has even earned the moniker “Sexspionage,” a term that reflects a societal bias linking espionage to the “second-oldest profession.” The tactic underscores how traditional gender dynamics continue to shape women’s roles in intelligence, painting them as manipulative rather than resourceful, regardless of the real risks they take and the complexities of their missions.

Popular culture has only added to the allure—and stereotype—of female spies as glamorous and seductive figures. Early spy novels and films often depicted male heroes as strong and intelligent, while women appeared as secondary characters, “Bond Girls” in the James Bond series who were meant to distract or fall for the hero. Even recent portrayals, while attempting to add complexity to female characters, rarely escape the allure of the “femme fatale.” This enduring cultural image has

made it difficult for real-life female operatives to be seen as skilled professionals despite their significant contributions.

Even within foreign service roles, cultural barriers persist. In regions where female authority figures are uncommon, such as parts of Latin America and the Middle East, women may face additional challenges in gaining the trust and respect of local officials. These challenges prevent many women from attaining the leadership positions they aspire to in intelligence agencies, where key foreign assignments often serve as stepping stones to higher ranks.

Despite these obstacles, the achievements of women in espionage underscore a necessity for reevaluating and challenging traditional gender norms within the intelligence field. Women have continuously proven their strengths and skills within espionage, particularly in intelligence work that values subtlety, patience, and analytical insight. Yet, they remain less celebrated due to the secretive nature of their missions and an enduring reluctance to see them as equals in roles of national significance.

While intelligence work has offered women a rare pathway into national security, the systemic inequalities they face highlight broader issues within society. Until these biases are addressed and dismantled, the intelligence community will continue to reflect the inequalities it aims to protect against. Women have proven time and again their invaluable role within the world of espionage, but true change requires both systemic and societal shifts. Their contributions may remain hidden in shadows, but the legacy they build in the field of intelligence speaks volumes about their resilience, courage, and professionalism.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.