Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

In political life, duplicity is not always a defect. It can often be a necessary virtue, a way of negotiating the messy terrain between principle and pragmatism. But there is a threshold beyond which duplicity turns into decay—a point where the performance of principle becomes indistinguishable from the betrayal of it. In the case of Jammu and Kashmir, and more specifically in the increasingly theatrical choreography of National Conference’s internal contradictions, we are perhaps witnessing that moment of decay. It is not the compromise that alarms, but the disingenuousness of the actors involved and the intellectual vacuity of their self-justifications.

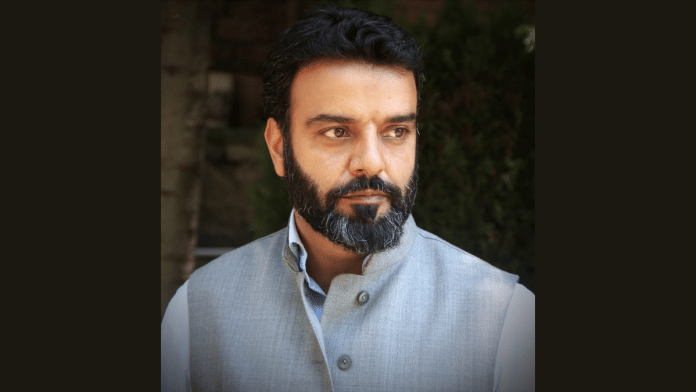

Aga Ruhullah Mehdi, Member of Parliament and so called conscience-keeper of the NC, has cultivated a public persona rooted in rhetorical resistance—resistance to the Centre’s heavy-handedness, to Delhi’s moral complicity in Kashmir’s dehumanisation, and to his own party’s well-documented history of moral retreat. But there is something disturbing about the rhythm of his dissent. He criticises what he helped enable, distances himself from decisions he campaigned for, and performs the politics of rupture while remaining ensconced in the apparatus of power. He is, in many ways, the most dangerous kind of politician—not because he acts, but because he pretends not to.

His protestations against the reservation policy—a policy that dramatically reduced the open merit share and was introduced by the very government he helped campaign for—are a study in political theatre. A cabinet sub-committee was set up, a six-month deadline announced, and then, predictably, the deadline disappeared into the bureaucratic ether. Six months and more have passed, and not even the ghost of a report has emerged. Yet Mehdi continues his carefully choreographed dissent, as though the party machinery he represents and the government machinery he disowns exist in separate ethical universes. His voice rings out with the tone of resistance, but his actions never quite rupture the architecture of privilege he inhabits.

There is, of course, nothing novel about politicians playing both sides. Omar Abdullah himself has long perfected the balancing act—professing allegiance to Kashmiri dignity when out of power, and performing ritual gestures of loyalty to the central government when in. But Omar’s politics, for all their shallowness, are at least visible in broad daylight. His allegiances are transactional, but not opaque. He makes his peace with compromise and does not bother disguising it with the language of transcendence. Mehdi, on the other hand, thrives on ambiguity. He must appear as the last moral man in a crumbling republic, while quietly ensuring that the republic continues to crumble under his watch.

The question then is not merely about individual hypocrisy. It is about what Mehdi’s behaviour reveals about the pathologies of Kashmiri politics at large. The NC, already hollowed out by decades of opportunism, appears now to require such figures to preserve even the illusion of moral relevance. The party has become a contradiction unto itself—a political body that requires dissenters to maintain its legitimacy, while doing nothing to address the roots of that dissent. In this sense, Mehdi does not threaten the party; he sustains it. He gives it a semblance of conscience, the performance of friction that saves it from total collapse into irrelevance.

But there is a deeper irony at play here. Mehdi’s rhetoric, often wrapped in the language of resistance and dignity, sits uneasily with his silence on more fundamental betrayals. He says little about the larger structural erasures—the demolition of Article 370, the ongoing incarceration of Kashmiri youth, the throttling of democratic institutions in the Valley. His interventions are episodic and selective, often triggered more by the optics of protest than the substance of governance. His critique is loudest when the issue is safely circumscribed—reservation policies, for example—where he can feign moral distance without actually taking a political risk.

This selective dissent is dangerous not merely because it is dishonest, but because it fragments the moral vocabulary available to the people. It reduces politics to a series of performative disavowals, where the central question is no longer what you stand for, but what you are seen standing against.

The question of who needs whom—whether the NC needs Ruhullah or Ruhullah needs the NC—is, in this context, beside the point. The deeper malaise is that both are locked in a mutually reinforcing cycle of credibility laundering. The NC needs Ruhullah to pose as a party still tethered to conscience. Ruhullah needs the NC to project himself as the lone voice of moral rectitude. Together, they sustain a fiction—the fiction that dissent can be manufactured within the party system, that Kashmir’s political degradation can be protested from within the structures that enabled it.

It is tempting to call Mehdi a wolf in sheep’s clothing, but even that metaphor lends him too much intentionality. His politics is less that of the scheming predator and more of the calculating duckling—navigating the swamp not with predatory cunning, but with an instinct for camouflage. The swamp of Kashmiri politics is now filled with such ducklings—figures who claim to speak truth to power while dining with it, who mourn the loss of sovereignty while submitting quietly to its new custodians.

One cannot help but feel that the most dangerous function such figures perform is epistemological. They distort the criteria by which political virtue is measured. They turn politics into a theatre of signals, rather than a field of consequences. In doing so, they disarm the citizen’s capacity to differentiate between resistance and accommodation, between courage and choreography. And that, perhaps, is the most lethal form of political betrayal—not the betrayal of principle, but the erasure of our ability to recognise it. He reminds one of the courtiers in Brecht’s parables—figures who speak against the king only when they know he is listening, and only in tones he will find useful.

Finally, politics is judged not by the finesse of its rhetoric but by the weight of its sacrifices. Mehdi’s politics, for all its moral inflection, remains feather-light. It floats atop the swamp but never disturbs its stillness. He is not the wolf in the henhouse. He is the duck who quacks just enough to make us forget how quiet the pond has become.

By: Zahid Sultan (Freelance Researcher. PhD in Politics and Governance from Central University of Kashmir. Email: Zahidcuk36@gmail.com

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.