Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

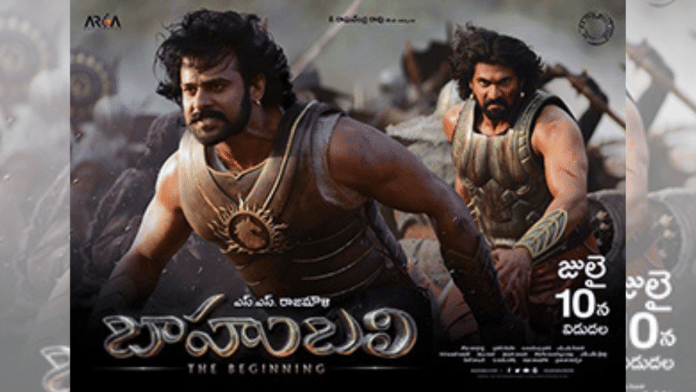

Since the release of Baahubali, Telugu cinema has been experiencing an upward trajectory in all aspects of filmmaking and has rightfully secured its place among Indian audiences. Increasingly, more movies are receiving the necessary funding, along with additional resources for marketing and desired media coverage. This is fantastic for Telugu culture, filmmakers, and audiences, who often revere the lead actors as demi-gods. In this seemingly all-encompassing win-win situation lies a seldom-discussed secret: a significant portion of the overseas revenue from Telugu cinema comes from overpricing customers, sometimes charging up to five times the average cost. (Disclaimer: The findings on ticket prices in this article are specific to Telugu movies in one Midwestern state of the United States where I currently reside)

Throughout the history of Indian cinema, Hindi language movies have dominated the landscape, with their geographical reach spanning the entire Hindi heartland. Its substantial influence reached non-Hindi speaking states such as Maharashtra, Gujarat, Punjab, and West Bengal, thanks to linguistic similarities. The six states where its influence is not dominant are Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, and Odisha. These states speak five different languages, all of which are recognized as classical languages by the central government. Here, due to fewer linguistic similarities and narratives rooted in local culture, native language cinema has always enjoyed more prominence compared to Hindi cinema. When a movie earns substantial profits either through its wide reach or repeated viewings, it attracts more individuals to the profession, thereby enhancing overall quality. With increased budgets, filmmakers gain the freedom to undertake ambitious projects, thus initiating a virtuous cycle of improvement. Regional cinema in India, with its limited reach confined to individual states, historically generated less overall profit compared to Hindi cinema. This began to shift in the early 2000s when Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam movies started gaining audiences in neighboring states on a limited scale. This laid the groundwork for what we now recognize as Pan-India movies, where films are dubbed into multiple Indian languages, expanding their reach beyond their traditional audience.

Indian cinema has effectively capitalized on additional revenue streams from NRIs (Non-Resident Indians). Overseas Indians find joy in accessing entertainment in their native language. Some estimates indicate that overseas revenue accounts for 20-25% of the total gross movie revenue, underscoring its significance. What began as a genuine market expansion has been overshadowed by greed and a blatant disregard for customers. Ticket prices for Telugu movies typically reach $15, which is three times higher than the average price of $5 for English and Hindi movies. Prices escalate further for movies featuring popular actors such as Prabhas, Ram Charan, NTR Jr, Mahesh Babu, Pawan Kalyan, among others. The highest amount I paid for a single ticket was $25 nearly five years ago, for a movie starring Pawan Kalyan, which is five times the average cost. Among my friends, we humorously speculate that ticket prices for the upcoming movie “Kalki 2898 AD” will begin at $50. The distributor sets these prices assuming NRIs are professionals with white-collar jobs who can afford to spend more without hesitation. However, this assumption is flawed, as not all professionals have substantial disposable income. Distribution rights in overseas markets are not centrally controlled; instead, they are auctioned to the highest bidder in each region. As demand grows and more players enter the market, bidding wars for distribution rights have escalated, significantly raising procurement costs and consequently increasing ticket prices for moviegoers.

Some may argue that it’s an open market where people are free to choose whether to watch a particular movie or not, and while this is true, history often shows that unrestricted market capitalism can lead to negative consequences. The movie industry stands out in comparison to sectors like food, manufacturing, real estate, and electronics, as it operates without any form of price control. For example, certain apartments in New York are subject to rent control, and Michigan has laws against price gouging during certain circumstances. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some grocery stores in the metro Detroit area were investigated by the attorney general’s office for price gouging. Unfortunately, this law does not apply to movie tickets, as they are consistently categorized as special events during purchase. In the automotive and electronics sectors, customers have the option to visit different dealers or outlets if they are dissatisfied with the price. However with movies, with only one distributor operating in a specific geographic region, customers often have limited alternatives.

Production houses may distance themselves from pricing decisions, attributing them to distributors. However, they overlook their significant influence on distributors, as they retain full control and ownership of the product. By setting conditions in bidding processes that prohibit overcharging customers, production houses can ensure distributors are mindful of market dynamics and bid accordingly. Distributors could be allowed a margin above average prices to cover higher costs associated with renting screens for shorter durations and logistics at scale. With clear pricing guidelines in place, moviegoers would likely be satisfied and may even consider returning for repeat theatre viewings rather than waiting for the movie’s OTT release.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.