Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

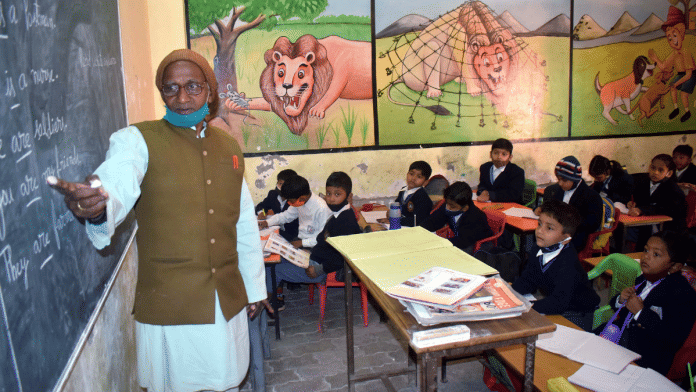

Haryana is one of India’s richest states, but its classrooms tell a different story.

Behind the statistics of growth and industrial development lies a quiet failure: the systemic deficit of basic science education in public schools. While highways expand and factories grow, children in rural Haryana still struggle to explain why the sky is blue. The problem isn’t new. It’s old, systemic, and worsening. Outdated teaching methods, insufficient teacher numbers, and a system based on memorization have deprived students of genuine learning and critical thinking. Girls are hit hardest. Many drop out early, discouraged by poor sanitation, social pressure, or simply the absence of encouragement—why should I study when I can work at an early age?—they think. Haryana may lead in income, but it is falling behind where it matters most: the minds of its next generation.

Haryana runs over 14,000 public schools under its education board. But in science, Class VIII students score well below the national average. In 2017, they averaged 42%, trailing the 57% national mean. In rural areas, the figure was closer to 48%. Post-pandemic, it fell further—to 45% in science and 42% in math. The ASER 2024 report confirms the trend: less than half of Class VIII students could answer basic science questions Such as Newton’s laws.

This crisis is gender and culture-based. Haryana’s sex-ratio is skewed at 879 females per 1,000 males. In classrooms, that gap becomes a chasm. Girls in Class VIII lag 7 percentage points behind boys in science. The reasons are sadly familiar to India: early marriage, domestic work, poor sanitation in schools, and a lack of encouragement. These learning barriers become more prominent the more we delve into rural India.

This crisis isn’t just about poor grades. It’s about the future. Poor science education leads to lower adoption of technology, lower productivity, and fewer opportunities. NITI Aayog’s former Vice-Chairman Rajiv Kumar warned as early as 2019: “Improving science education is crucial for India’s economic growth, and states like Haryana must address this challenge urgently.” Yet Haryana’s budget tells a different story. In 2024–25, only 13.8% of its total budget was allocated to education, down from 16.3% the previous year. Outcomes remain flat.

The problems are deep, but they are not insurmountable. The system is weighed down by predictable culprits: outdated textbooks, rote learning, teacher shortages—24% vacancy rate—and most importantly, lack of excitement to learn. But there is a way forward—an approach already backed by evidence, neuroscience, and behavioral science: gamification.

Gamification is not about making school “fun”, it’s about redesigning the learning process using proven principles from game design. These elements stimulate the brain’s reward system, fostering engagement and motivation. The science is clear. Self-Determination Theory (1985) identifies autonomy, competence, and relatedness as the drivers of true, lasting motivation—three elements that good gamified design delivers.

Studies back this up. A July 2024 trial reported gains in cognition, participation, and behavior in science classes using gamified tools. Simulations and virtual labs in STEM helped students move to actual understanding.

So, what would gamification look like? Well, it’s two-fold.

Firstly, Gamified apps must be built ground-up in Hindi and Haryanvi—urban models fail rural kids facing chores, outages, and no exposure.

Secondly, Gamified learning must be teacher-led and gender-sensitive. Without training or RCTs, it becomes noise—not impact—in India’s diverse classrooms.

Critics say gamification is shallow. And they’re right to worry: bad gamification is worse than none. Adding points to poor teaching does not fix anything but only accelerates an already dismal state. But good gamification is guided by learning science, not gimmicks. To avoid burnout and competition-induced stress, modules must be refreshed regularly–to add the variety that fuels interest. Cooperative challenges must be part of the system. Leaderboards must track effort and growth Raw scores should not be tracked, we don’t want to create an online model of the CBSE exams.

Furthermore, connectivity remains patchy. Despite 6,600 smart classrooms, rural Haryana lacks stable broadband. The fix: offline kits and low-bandwidth modules.

It is time for Haryana to stop admiring the problem and start fixing it. A rigorous, state-funded trial of gamification in public schools could offer exactly what is missing: curiosity, clarity, and confidence in science. Budget allocations should reflect not just the number of schools built, but whether students inside them learn.

Gamification is not about replacing tradition. It is about updating it. It keeps the structure of classrooms intact, but reinvents how students interact with knowledge. Haryana’s children deserve more than dusty textbooks and broken chalkboards. They deserve a system that makes them want to learn and equips them to do so.

The future of Haryana’s science education may depend on something that looks like a game but feels like hope.

The author of this article is a student at the Shri Ram School Aravali. Views are personal.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.