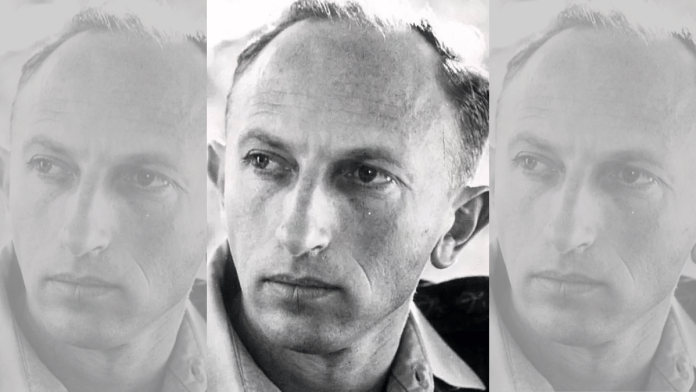

New Delhi: On 2 January 2024 — just two days into the new year — Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office announced the death of Zvi “Zvika” Zamir, the former director of the country’s formidable intelligence agency, Mossad. Zamir, who led the agency in combating terrorism in the aftermath of a deadly attack on Israeli athletes during the 1972 Munich Summer Olympics and the Yom Kippur War in 1973, was 98 years old when he passed away.

“His tenure as director of the Mossad were (sic) characterised by extensive action, while dealing with significant challenges, especially the fight against Palestinian terrorism around the world and the military threat to the State of Israel, which peaked with the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War,” the statement published by Netanyahu’s office said.

Zamir was appointed as the director of the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations, popularly known as Mossad, in 1968. His tenure coincided with rising terrorist attacks against Israelis and Israeli assets across the world — especially aviation hijackings by Palestinian militant outfits such as the Black September Organization and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

Between the start of his tenure on 1 September, 1968, and its end in 1974, there were at least 16 attempts of aviation terrorist attacks against the Israeli carrier El Al, according to a research paper by Łukasz Szymankiewicz.

Black September also successfully assassinated Ami Shachori, an Israeli diplomat at its embassy in London, via a letter bomb in 1972.

These rising attacks against Israelis culminated in the Munich massacre when eight Black September terrorists gained access to the lodgings of Israeli athletes in the Munich Olympic Games village in the early hours of 5 September 1972.

Eleven Israeli athletes were killed in the attack while four militants were shot down during an hour-long firefight at an airfield while they were attempting to flee to Cairo with nine hostages.

Zamir’s efforts to deter such attacks against Israelis — especially abroad — in the aftermath of the Munich massacre gave Mossad the reputation of being one of the best in the business at hunting down threats.

The intelligence agency’s efforts to hunt down those responsible for the Munich massacre have occupied the public imagination since, inspiring works such as Vengeance a 1984 book by Canadian author George Jonas, based on which Steven Spielberg made his critically acclaimed 2005 film, Munich.

Zamir, however, wasn’t impressed with the film, which was nominated for five Academy Awards that year — ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Director’, ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’, ‘Best Editing’, and ‘Best Score’.

In a 2006 interview with Haaretz, Zamir called it a “crappy” movie deserving “opprobrium” and not an Oscar.

Despite his role in cementing the organisation’s reputation for its counter-terrorism operations around the world, however, Zamir is best remembered for his warnings of an imminent attack by Egyptian and Syrian forces on the holiest of Jewish holidays — Yom Kippur.

In 2023, the Israeli state archives released details of a warning that Zamir received from a highly placed Egyptian source that Egypt and Syria were about to attack. According to media reports, this source, later revealed to be Ashraf Marwan — son-in-law of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser — warned Zamir at a meeting in London that there was a “99.99 percent chance” that the attack would be on the next day, that is, on Yom Kippur.

Those warnings went unheeded, leading to the Yom Kippur War in 1973, also known as the Fourth Arab–Israeli War.

In his 2005 book The Watchman Fell Asleep, Israeli historian and author Uri Bar-Joseph called the war the “most traumatic event in Israel’s stormy history”.

Also read: Indians have a Mossad fantasy. But 2 weeks show even strong states crumble

Munich massacre and its aftermath

One cannot have a “true reading” of the history of Israel, without understanding the “secret history” of its intelligence services, journalist Ronen Bergman, an Israeli investigative journalist, said in the 2017 documentary Mossad: The Secret Service of Israel.

An important inflection point in the operating procedures of Mossad is in the aftermath of the Munich massacre.

As Bergman explains in the documentary, “(The) Munich Olympic Games terrorist operation changed Israeli policy for many years. Because after that the Israeli cabinet allowed Mossad to kill Palestinian operatives in Europe, even though it was in blunt violation of any rule, of any law.”

Zamir, as the director of the organisation, led that operation. Born Zvicka Zarzevsky on 3 March 1925 in Lodz, Poland, Zamir’s family emigrated to what was then the British Mandate of Palestine when he was a baby.

Zamir grew up playing football with future Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and had his name changed as a teacher of his — reportedly Israel Prize-winning author Yehuda Burla — could not pronounce Zarzevsky. In 1942, at age 16, he joined the Palmach, the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the main Zionist paramilitary organisation in the British Mandate of Palestine, whose aim was to protect the Palestinian Jews.

He went on to become a two-star general in the Israeli army (Israel Defense Forces or IDF) and after heading the Southern Command was made the military attaché to the United Kingdom, according to Israeli online newspaper The Times of Israel.

It was from there that then Israeli prime minister Levi Eshkol brought him back to Tel Aviv and appointed him the fourth director of Mossad, just a few weeks after the 1968 hijacking of El Al Flight 426 by the PFLP.

In 1972, after the Munich massacre, Zamir was sent to Germany on the orders of Golda Meir, the prime minister of Israel. There, the former IDF two-star general witnessed a scene he said he would never forget for the rest of his life.

“With their hands and feet tied to each other, the athletes trudged past me. Next to them, the Arabs – a deathly silence…It broke my heart. The Palestinians threw a grenade into the helicopter and it burst into flames,” said Zamir in the documentary Mossad: The Secret Service of Israel’.

In his report to the Israeli cabinet on his return, he lamented that the German police forces did not even make “a minimal effort” to “save people, neither theirs nor ours”, according to documents found in the Israeli State Archives, the country’s official database for such documents.

In a written report to Meir, Zamir concluded that the German operation was carried out “poorly and ineptly, which led to the tragic outcome” of the death of all the captured athletes, according to one of these documents, titled ‘The Munich massacre, September 1972’.

Another set of documents, titled ‘Aftermath: hijacking of a Lufthansa plane and the release of the Munich terrorists cause outrage in Israel’, shows that Zamir asked his West German counterpart during his visit what would happen if a Lufthansa plane were hijacked to force authorities to release the three surviving terrorists from the Munich massacre.

When the West German intelligence chief could not promise that they wouldn’t be released, Israel began seeking the militants’ extradition.

A month later, however, the hijack of a Lufthansa flight from Beirut to Munich forced the West German authorities to do exactly what they could not promise. On 29 October, 1972, the three surviving Black September militants, Adnan Al-Gashey, Jamal Al-Gashey, and Mohammed Safady, were released in exchange for the hijacked Lufthansa Flight 615.

In the aftermath of the Munich attack, Meir put Zamir in charge of ‘Operation Wrath of God’ — a military operation to take down terrorist organisations and their infrastructure in Europe. It was not a campaign of “vengeance” but more a “preventive measure” against future attacks, Zamir said in his 2006 interview with Haaretz.

“In some of my conversations with Golda, she expressed her concern that our people might be involved in illegal actions on European soil. It was indeed unavoidable, but illegal,” Zamir told the interviewer.

He further said: “There is no defence without an offensive foundation. We knew the modus operandi of the terrorist organisations, and because they did not send battalions of terrorists to Europe, but individuals. We decided to deal with their liaison people, their officers, their representatives, their means of transportation in Europe”.

He added then that in the wake of the war after Munich, Mossad was able to put an “end” to the type of “terror” that was being perpetrated against Israel.

Also Read: Israel’s first PM called Nehru a ‘great man’. Asked him to moderate peace in the region

Yom Kippur War

Zamir’s actions in the aftermath of the Munich massacre are, however, dwarfed by his intelligence warnings of a combined Egyptian-Syrian attack against Israel on Yom Kippur just over a year later.

Zvika received an urgent message in October 1973 from a high-level Egyptian informant, later revealed to be Marwan.

Also known as ‘The Angel’, Marwan called for a meeting with Zamir in London — a request to which the director of Mossad immediately acceded, author Bar-Joseph writes in his book The Watchman Fell Asleep.

When Zamir met him on 5 October 1973, at 10 pm local time (11 pm in Israel), the Angel informed him that Egypt and Syria were “99.99 percent certain” that war would start the next day at around sunset, writes Bar-Joseph.

The Mossad chief immediately passed on the message to bureau chief Fredy Einy, who, at 3:40 am on 6 October, called the military secretary to the prime minister to inform them of it, the book says.

Moreover, while Zamir’s warnings were heeded to a degree by the IDF and its chief of staff David Elazar, he faced pushback from Moshe Dayan, the minister of defense. According to Bar-Joseph, within minutes of receiving Zamir’s warning, Elazar was on call with the commander of the Israeli Air Force and instructed him to prepare for a preemptive strike against Egypt and Syria. However, Dayan refused to allow this over concerns of an adverse reaction from the White House to Israel’s offensive actions.

As the IDF began to prepare, the Egyptian and Syrian forces attacked at 2 pm on 6 October 1973, and with that began the Yom Kippur War.

Despite Zamir’s warnings, Israel was caught unprepared and this led to losses among the Israeli forces. Zamir left Mossad in 1974 and went on to have a successful career in private business before being appointed in 1995 to the Shamgar Commission to investigate the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

Despite the setbacks before the Yom Kippur War, Zamir still believed that his greatest achievement as the Mossad director was the early warning that he gave Israel.

“In my view, the greatest achievement of the Mossad in my term of office was the information about the preparations made by Egypt and Syria to go to war and the warning we provided about the war. That, of course, is the achievement of everyone in the Mossad, not mine,” Zamir told Haaretz in 2006.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: ‘Agent A’ & ‘Agent K’, two women at the top of Mossad make it an unusual first