By Emilie Madi and Suleiman Al-Khalidi

BEIRUT/AMMAN (Reuters) – The prospect of the U.N. agency for Palestinians (UNRWA) being forced to shut down services by the end of February is deepening despair in refugee camps across the Middle East, where it has long provided a lifeline for millions of people.

It is also causing concern in Arab states hosting the refugees, which do not have resources to fill the gap and fear any end to UNRWA would be deeply destabilising.

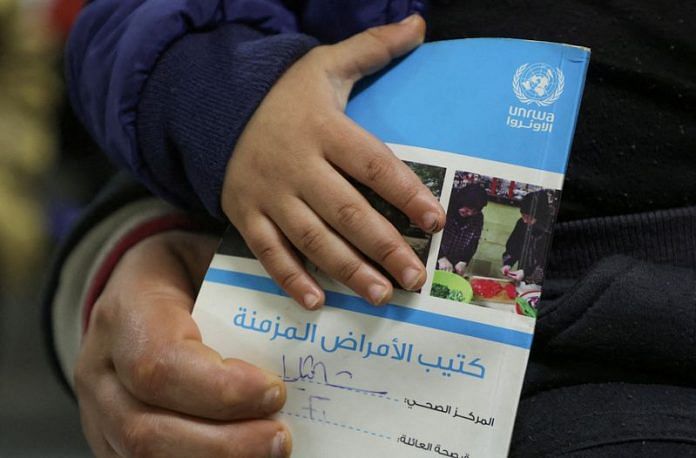

UNRWA, which provides healthcare, education and other services, has been pitched into crisis since Israel alleged that 12 of its 13,000 staff in Gaza were involved in the Oct. 7 Hamas-led attack on Israel that precipitated the Israel-Hamas war, prompting donors to suspend funding.

UNRWA hopes donors will review the suspension once a preliminary report into the assertions is published in the next several weeks.

For Palestinians, UNRWA’s importance goes beyond vital services. They view its existence as enmeshed with the preservation of their rights as refugees, especially their hope of returning to homes from which they or their ancestors fled or were expelled in the war over Israel’s creation in 1948.

In the Burj al-Barajneh camp on the outskirts of Beirut, Raghida al-Arbaje said she depends on UNRWA to school two of her children and cover medical bills for a third who suffers from an eye condition.

“If there is no UNRWA, I can’t do any of this,” said Arbaje, 44, adding that the agency had also paid for cancer treatment for her late husband, who died five months ago.

A shanty of feebly constructed buildings and narrow allies, Burj al-Barajneh depends on UNRWA in many ways, including programmes that offer $20 a day for labour – vital income for refugees who are barred from many jobs in Lebanon, Arbaje said.

She described the bleak situation for Palestinians in Lebanon, saying: “We are dead even as we live.”

Appealing to donors to keep funding UNRWA, she added: “Don’t kill our hope”.

RIGHT OF RETURN

UNRWA – the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East – was set up in 1949 to provide refugees with vital services.

Today, it serves 5.9 million Palestinians across the region.

More than half a million children are enrolled in its schools. More than 7 million visits are made each year to its clinics, according to UNRWA’s website.

“The role this agency has played in protecting the rights of Palestinian refugees is fundamental,” UNRWA spokesperson Juliette Touma told Reuters in an interview.

UNRWA has said the allegations against the 12 staff – if true – are a betrayal of U.N. values and the people it serves.

The Hamas-led attack killed 1,200 people and abducting another 240, according to Israeli tallies. Since then, an Israeli offensive has killed more than 27,000 people in Gaza, according to health officials in Hamas-run Gaza.

Israel wants UNRWA shut down.

“It seeks to preserve the issue of Palestinian refugees. We must replace UNRWA with other U.N. agencies and other aid agencies, if we want to solve the Gaza problem as we plan to do,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said on Jan. 31.

In Jordan, Palestinians have held protests against any such move. “The Destruction of UNRWA will not pass … Yes to the right of return”, declared signs held aloft at a Feb. 2 protest in Amman.

Hilmi Aqel, a refugee born in the Baqa’a Palestinian refugee camp, 20 km (12 miles) north of Amman, said his UNRWA ration card “proves that me and my children are refugees”.

“It enshrines my right.”

‘CATASTROPHIC’

Arab states hosting the refugees have long upheld the Palestinians’ right of return, rejecting any suggestion they should be resettled in the countries to which they fled in 1948.

In Lebanon, where UNRWA estimates up to 250,000 Palestinian refugees reside, the issue is infused with long-standing concerns about how the presence of the predominantly Sunni Muslim refugees affects Lebanon’s sectarian balance.

Lebanese Social Affairs Minister Hector Hajjar said decisions by donor states to suspend aid were unfair and political, and the repercussions would be “catastrophic” for the Palestinians.

“If we deny the Palestinians this, what are we telling them? We are telling them to go die, or to go to extremism,” he told Reuters in an interview. The decision would be destabilising for Lebanese, as well as Palestinians and refugees from the war in neighbouring Syria, he said.

In Jordan, the UNRWA crisis has touched on long-standing concerns. Jordan is home to some 2 million registered Palestinian refugees, most of whom have Jordanian citizenship. Officials fear any move to dismantle UNRWA would whittle away their right of return, shifting the burden onto Jordan.

Norway, a donor that has not cut its funding, has said it is reasonably optimistic some countries that had paused funding would resume payments, realising the situation could not last long.

The United States has said UNRWA needs to make “fundamental changes” before it will resume funding.

Moussa Brahim Dirawi, a refugee in Burj al-Barajneh in Beirut, expressed fear for Palestinian children were UNRWA schools forced to shut down.

“You are contributing to making a whole generation ignorant. If you are not able to put your children in school, you would put them on the streets. What would the streets raise?” he said.

(Writing by Tom Perry, Editing by Timothy Heritage)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Reuters news service. ThePrint holds no responsibilty for its content.