Kabul: Ariana, a mother-of-three who worked as a policewoman in Afghanistan’s Kunduz province, is left with many questions as she grapples with the country’s new reality, and her own new identity as an internally displaced person.

Accompanied by her three daughters, Ariana arrived in Kabul earlier this month, having fled her home as the Taliban reached her village and began “burning houses and terrorising women”.

Escaping over 300 km away from home was meant to guarantee safety and stability for her family, but, with Kabul now under the Taliban as well, that desire seems increasingly out of reach.

“We made a mistake leaving our homes and coming to Kabul, we didn’t realise the Taliban would take over the capital also,” she told ThePrint at the Khairkhana neighbourhood, which has emerged as a hub of internally displaced people (IDP) since word of the Taliban’s resurgence first caught wind. “Where will we go now?”

Ariana’s worries capture a larger sentiment of despair that now haunts Afghanistan’s army of IDP — people who escaped their homes in various provinces to arrive in Kabul, which was seen as a secure haven until 15 August, when the Taliban arrived here.

While the Taliban appear to be attempting to portray a softer turn this time around, there is much scepticism about their claims among Afghans who lived under their rule during a brutal five-year period between 1996 and 2001.

Since the Taliban overran vast swathes of the country following the announcement of the NATO pullout, reports have emerged about their various atrocities, including door-to-door searches for people “close to the government” and alleged “revenge killings”.

Women have been particularly on edge, stalked by memories of the Taliban’s earlier rule where they couldn’t as much as stir out of the house without a male family member, let alone study or work.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), an estimated 270,000 Afghans had been displaced inside the country between January and July 2021, primarily due to insecurity and violence, bringing the total uprooted population to over 3.5 million.

In July, UNHCR spokesperson Babar Baloch warned of an “imminent humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan”.

Also Read: On the roads of Kabul, anxiety, fear, terror & gunshots a day after Taliban take control

‘I don’t feel safe’

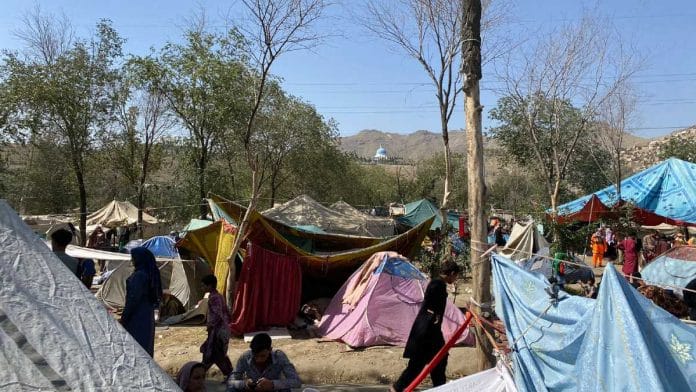

The sprawling ground in Khairkhana, a middle-class neighbourhood in Kabul’s north-west, is now crowded with tents. A local resident who didn’t wish to be named said the area currently houses 6,000 to 10,000 families of IDP who have arrived from Takhar, Kunduz, Kandahar and Samangan provinces.

The influx, he said, began in January 2021, “when it became clear the international troops will be leaving Afghanistan and the Taliban will come to power under a deal”.

Many tents, modest in size, accommodate families of as many as 12-15 members.

There is no proper washroom, no food or water supply, and the displaced Afghans allege they have been left at the mercy of some international aid agencies, whose presence has been thinning out as well, and local residents.

“We have nowhere to go. The world does not care, the country does not care, nobody cares for us…” said Tamanna, a 20-year-old from Kunduz. “What have we asked for? We just need a home and peace, why are we being neglected? Why has the world turned a blind eye to us?”

One of the Afghans at the camp said they had been seeking help from the erstwhile Ashraf Ghani government since early May, but none was provided. The Afghan police forces, they added, harassed them.

Meanwhile, for Ariana, the decision to arrive in Kabul seems increasingly questionable. Adding to her worries is her lack of information about her husband, who could not make it out of Kunduz.

“I do not know if my husband is still alive… I don’t feel safe in Kabul either. I want to go back,” she said. “I think I was safe there. Here, anything can happen to me and my daughters.”

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Escape from Kabul: How I negotiated with Taliban to make it to the safety of Indian embassy