London: Back in 2001, Kenneth Möllersten and Michael Obersteiner came up with a novel idea that transformed the math of carbon emissions — and the world’s path to net zero.

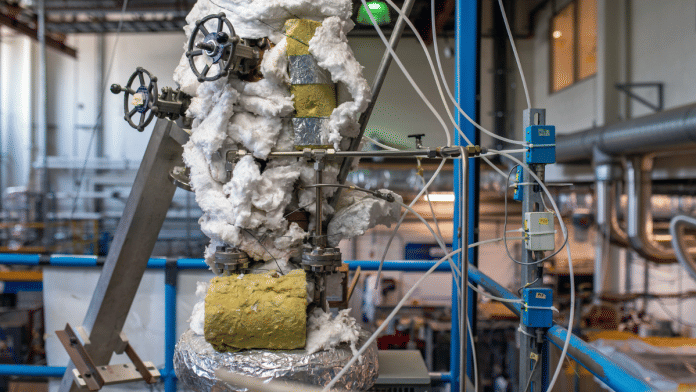

At the time, oil and gas companies were dabbling with capturing carbon from fossil fuels, a process that cut emissions from producing energy to nearly zero. By burning plants instead, the two researchers figured, the industry could generate energy with negative emissions: Those trapped in trees or other biofuels, minus those captured from burning them.

The concept helped pave the way for the world to adopt negative emissions as a central part of climate planning — it’s become a key element of official emissions-reduction plans submitted to the United Nations by major economies including the UK, Brazil and Australia.

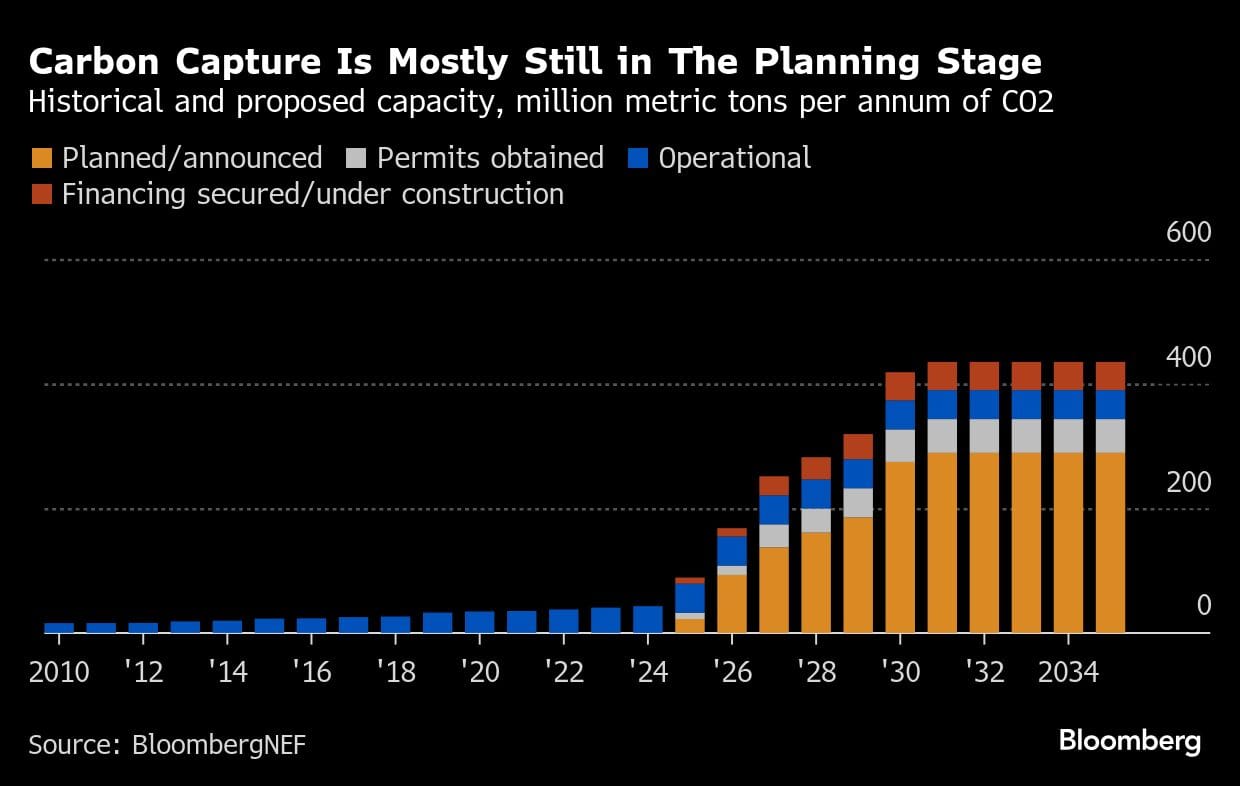

Ahead of COP30 in Belém, Brazil this week, most countries that filed emissions plans with net zero goals are relying on carbon removals to reach their target, according to analysis by the Climate Action Tracker, a partnership of climate researchers.

But Möllersten and Obersteiner are far from thrilled. The problem, they say, is that carbon capture was meant to cancel out past emissions. Instead, it’s bred an overconfidence that the strategy can substitute any hard-to-make cuts to fossil fuels.

Many countries, for example, are simply planning to overshoot their goals or haven’t bothered to spell out how they will reach them. Around 60 countries have updated their climate plans since the world agreed to transition away from fossil fuels at COP two years ago, but none of them included targets to cut oil and gas production. Some 20% of pledged emissions cuts, meanwhile, are unaccounted for in countries’ climate plans, the Climate Action Tracker group said. The assumption, it added, is that a lot of that will be captured.

“We emphasized that the potential of future negative emissions should never be used as an excuse to delay emission reductions,” said Obersteiner, who is now director of the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford. “We could get access to heaven for trying to solve the climate problem. At the same time, we should go to hell, because we created overshoot.”

What is overshoot?

“Overshoot” is the idea that it’s OK for the world to shoot past climate temperature targets because we can later remove carbon from the atmosphere. It became baked into the climate projections used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and later by governments to set their own climate targets, says Laurie Laybourn, executive director of the Strategic Climate Risks Initiative, a think tank that advises governments and firms on climate risk. (He interviewed Möllersten and Obersteiner for a podcast, Overshoot: Navigating A World Beyond 1.5C, which came out last month.)

The two researchers were among a group of scientists who back in the early 2000s were looking for a back-up plan if other emissions-reductions approaches, like renewable energy, failed to scale in time. And even if the world were on track to limit warming, a world even 1C or 1.5C hotter than the pre-industrial norm would have problems with extreme weather, they reasoned. At early climate conferences, Möllersten and Obersteiner pitched their idea as a way to bring CO2 concentrations back down and reduce these effects.

At the time, modeling suggested that reducing emissions enough to stop temperature rise was going to be difficult, and solutions like carbon removal looked attractive to scientists and policymakers working on climate change. In 2007, IPCC scientists took it up at a meeting, and included it in scenarios for how warming might be reduced.

“People were using these modeling results without knowing the assumptions and caveats,” said Laybourn. “It gave them the political cover to do something that was noble, which was to say, 2C is possible, 1.5C is possible.”

There have since been two decades of rising emissions. Reversing some of them is necessary if the world is to have any hope of reaching climate goals, Laybourn says. Every scenario that involves limiting warming to 1.5C and even to 2C involves carbon dioxide removal, the IPCC said in its most recent report.

A risky approach

But relying on carbon removals is risky for a couple of reasons.

Nature-based carbon removal, which involves planting trees and restoring other carbon sinks like peat bogs is limited by land availability. Capturing carbon directly from the air or from burning biofuels for energy, meanwhile, is in its infancy and needs a lot of financial support to scale.

It’s also unclear how helpful bioenergy is for reducing emissions, because wood products could instead be used for other purposes that don’t release any carbon, and the process of cutting and planting the trees can be emissions-intensive. Direct air capture uses a significant amount of energy, and the availability of land to store the captured carbon is also limited.

The other problem is that relying on carbon removals rather than cutting emissions in the immediate term increases the risk of sudden consequences of climate change, like the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, the ocean current that warms Europe.

“We are every day rolling the dice and it could end up rolling onto a tipping point,” said Laybourn. “Going over 1.5C puts us in this intolerable danger zone that we need to get out of as quickly and as best as possible.”

How do Möllersten and Obersteiner feel about what has happened to the idea they had so much hope for as a solution to climate change? They say they tried their best to make it clear that these technologies were an add-on, rather than a replacement for emissions reductions.

Nevertheless, they still feel disillusioned by the experience. “I am not surprised,” says Möllersten. “It is quite disheartening and confirms that it is very challenging for man to act decisively on an abstract existential threat that will primarily impact future generations.”

(Reporting by Olivia Rudgard)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also Read: In a first, 12 member-states sign agreement to combat climate disinformation at COP30