For decades, Iran has been the nexus of global geopolitical risk. Its potential to create chokepoints in the flow of oil is ingrained in the minds of traders, with the Strait of Hormuz posing the biggest risk. But for all the recent focus — and hype — on the possibility of military conflict, the largest danger is far more mundane: A labor market strike by the nation’s oil industry employees. The distinction is important because while the risk of a US attack has receded, the potential for labor unrest has paradoxically increased. The former scares the market but rarely impacts on supply; the latter is overlooked — but historically has triggered large production outages.

Is Iran’s oil industry about to be shut down by protesting employees? Probably not. Resorting to brutal repression, Tehran last week contained the latest wave of protests. The death toll probably runs into several thousands, perhaps the worst state violence in the regime’s 47-year history, surpassing the killings and mass executions of 1988, 1999, 2011 and 2022. For now, the Islamic Republic has regained control of its major cities.

For President Donald Trump, who initially encouraged the rioters and hinted at a bombing campaign with his “help is on its way” message, it was enough. “We’ve been told that the killing in Iran is stopping — it’s stopped,” Trump said on Jan. 14. Asked if military action was now off the table, Trump said he would “watch it” and “see what the process is.”

But it’s a false closure. The regime can kill protestors but it can’t solve the economic crisis at the root of their grievances. Inflation, running close to 50%, remains unchecked: Iran’s currency, the rial, is in free fall; and unemployment is increasing. Unless the authorities solve the cost-of-living crisis, instability is likely to continue, and with it the risk of turmoil in the oilfields.

While American and European sanctions, alongside low oil prices, are hurting Iran, the real problem is the increasingly corrupt, kleptocratic and militarized nature of its economy. The inner circle of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), a powerful military organization, control a wide range of local companies. Without economic reform, which necessarily means a wholesale political change, Iran is inexorably heading toward more turmoil. Raz Zimmt, an Iran analyst at the Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies, wonders whether the country might be at the “beginning of a period of civil disobedience” characterized by “sporadic” eruptions.

The 2018-2019 wave of protest, which saw nationwide strikes in some sectors, including transportation, offers a blueprint. Even though his influence is tenuous, Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of the Shah of Iran who was deposed in the 1979 revolution, merits attention: On Jan. 10, he called on protestors to cut off the “financial lifelines” of the regime. “I invite workers and employees in key sectors of the economy, especially transportation, oil, gas, and energy, to begin the nationwide strike,” he said on social media.

History shows that walkouts can have a huge impact on the country’s hydrocarbon output. In mid-1978, Iranian oil production collapsed by about 80% in a matter of weeks after workers went on strike, paving the way for the revolution that gave power to Ayatollah Khomeini a year later. It remains to this day the largest ever oil outage.

In the almost half a century since then, lots has changed. Today, the IRGC closely controls the industry, in some cases owning major pieces of oil and gas infrastructure and employing its own loyal workers. Moreover, the security apparatus keeps a tight grip on two provinces — Khuzestan, and Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad — that are home to the country’s biggest oilfields. Third, many oil employees are contract workers with little job security and meagre finances, who are unlikely to race to join any strike on the first call for action.

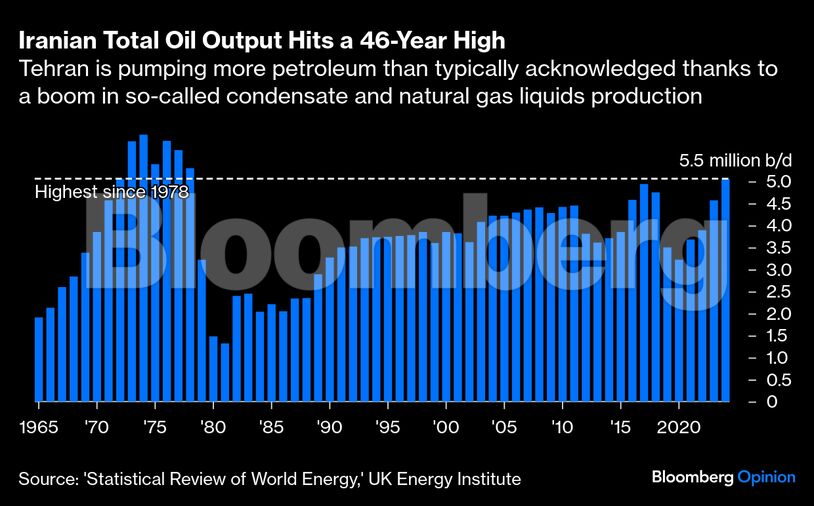

For now, the potential of internal disruption in the Iranian oilfields — which today produce nearly 5 million barrels a day of crude and other petroleum liquids, about the same as in 1978 — is a low-risk but high-impact scenario. Importantly, it’s a threat that’s outside the control of Trump. The White House can calibrate any military action to avoid the oil sector, as it did in June when it urged both Israel and Iran not to bomb each others energy facilities. But it can’t control what protestors do on the streets of Iran — or in its oil fields. More than the bombs, keep an eye on the workers.

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.