Sydney: When Australia announced plans to restart its economy after the coronavirus shutdown, authorities worried Sydney would be flooded with cars as socially distancing commuters returned to work.

But more than a week after schools and many businesses reopened, emergency parking lots created to accommodate an influx of new drivers are nearly empty. Traffic levels are edging back to pre-lockdown levels, according to TomTom, yet there’s little sign of people taking to cars en masse. Nor are they piling back onto buses, with only limited reports of overcrowding.

The muted return of commuters in a country with comparatively few virus cases — there have been just over 100 deaths in Australia, compared to more than 20,000 in New York — may be early evidence of an enduring shift in behaviour.

“We are seeing something different to a simple snapback,” said Jago Dodson, director of the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT University. “The immediate imperative to rush the workforce back into corporate office towers in the CBDs is perhaps not as strong as you might imagine.”

If the virus changes working patterns to keep even a small proportion of people from commuting to city centers, it could help solve a problem that urban planners have failed to crack for decades. Outside of one-off events like the Olympic Games, policymakers have struggled to spread transport demand away from peak times.

“We’ve been trying since the 1940s to stagger start hours to reduce pressure on the transport network and it’s just never worked,” said Geoffrey Clifton, a transport expert at the University of Sydney. “9 to 5 is still 9 to 5.”

Shifting hours and more work-from-home jobs would mean more efficient use of the transport network, saving billions of dollars in investment, he said.

It’s not like Australians are hunkered down at home. More than eight out of 10 households in the nation own at least one car, one of the highest rates in the world, and suburban beaches and parks are buzzing. Pubs are preparing for a surge in thirsty clients this weekend.

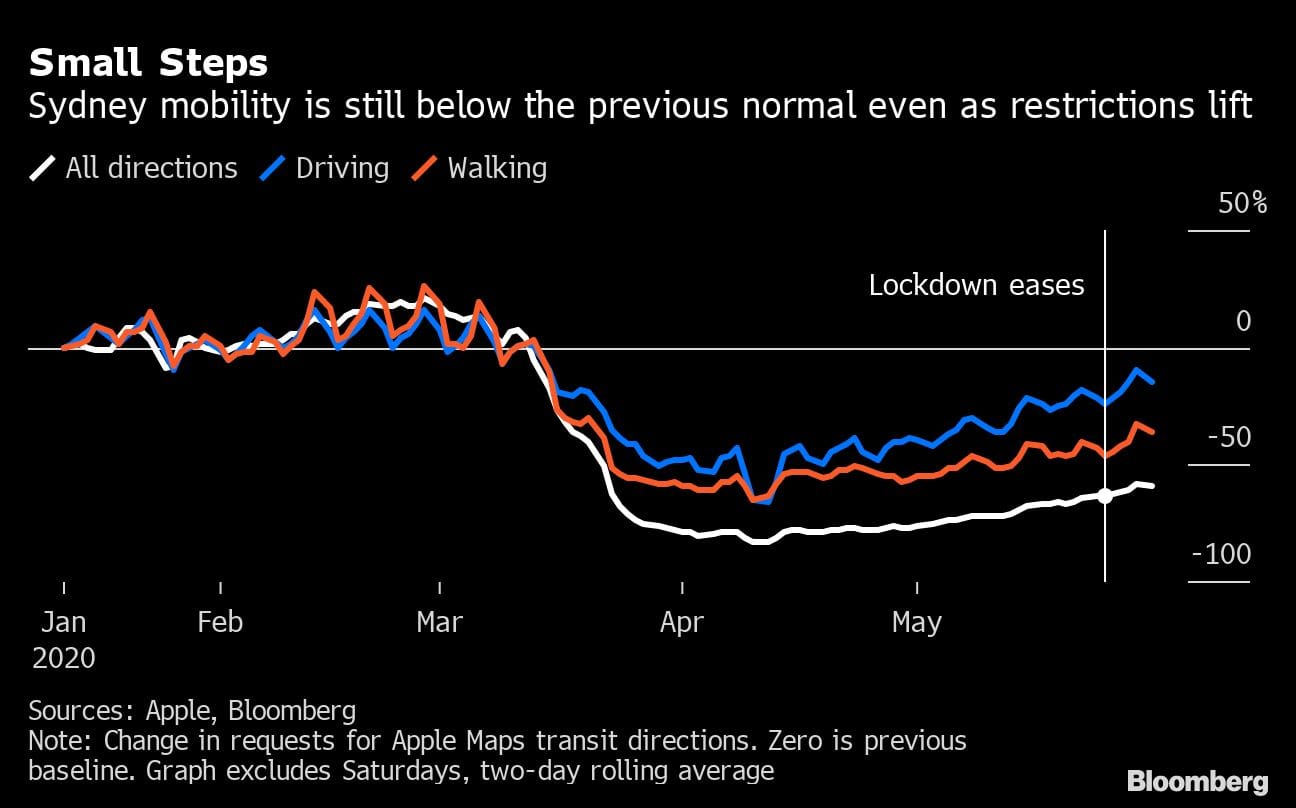

At the same time, Apple Inc. data show that routing requests on June 2 for all travel were down nearly 60% from pre-virus levels.

“People just aren’t ready to return to work,” Clifton said. “I genuinely was surprised. I thought there would have been a lot more people going back.”

One factor is that some of the biggest job losses have been in sectors like retail and hospitality, which are concentrated in central areas, trimming the number of commuters. Another is that many offices are grappling with issues like lift capacity and seating plans and are staggering the return of staff. Some employers, after investing in remote-working technology, found productivity was better than expected and aren’t planning to return to the old ways.

Telecoms giant Optus says it will keep some staff at home permanently and Westpac Banking Corp. is also mulling a long-term shift.

It’s too soon to call the end of the office commute. Surveys suggest two or three days a week in the office is the ‘sweet-spot’ for many workers to balance the benefits of face-to-face interaction with those of working from home, said Libby Sander, an organization behavior expert at Bond University.

“The office is not dead,” said Andrea Roberts, national head of leasing at real estate company Knight Frank Australia. “The return to work has been slower than expected, absolutely. But the office might even become a more important amenity and culture hub. People need something to bring them together.”

It’s been a similar cautious return in other Asian cities. In Hong Kong, the major banks sent back only between a third and half of their staff when restrictions first started to lift. In Singapore, Citigroup Inc. said it plans to keep 88% of its 8,500 employees at home until July.

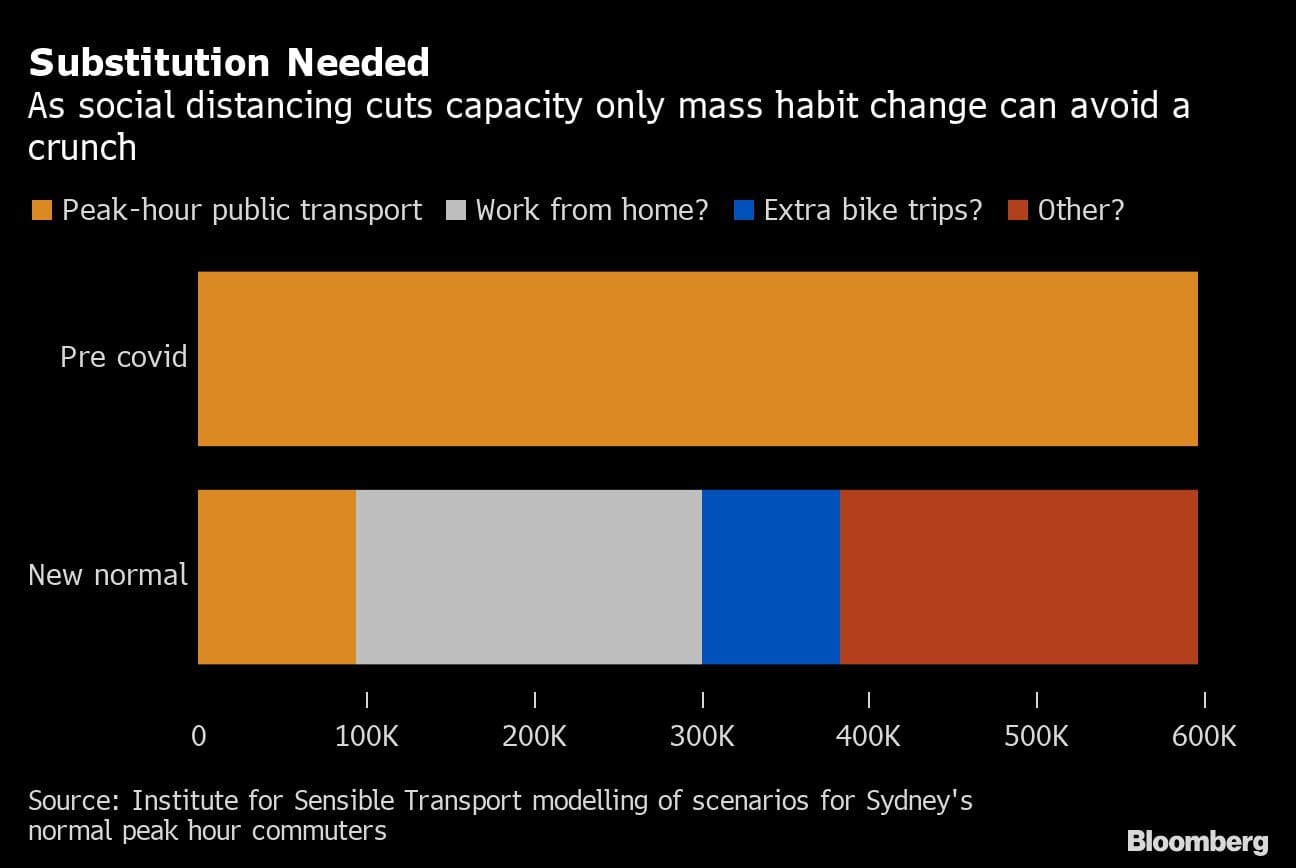

Limited returns could be vital to enforcing social distancing on trains and buses. In the past, 60% to 80% of those working in Sydney’s city center arrived by public transport, according to the Institute for Sensible Transport. Depending on how strictly social distancing is enforced, between 50% and 85% of the normal 600,000 peak-hour commuters would need to find an alternative, researcher Elliot Fishman estimates.

“There just isn’t enough car parking capacity to absorb the extra, say, 200,000 cars that could potentially be headed for central Sydney at peak hour,” Fishman said. “It could bring traffic congestion beyond anything we’ve ever seen in this country.”

Keeping some of those cars from coming in each day could be one lesson to learn from the pandemic.

“We’ve been fairly slow in transitioning our urban transport systems to a more sustainable mode,” said Dodson at RMIT. “Now is the time when we could really start to accelerate that transition.” – Bloomberg

Also read: Australia to toughen foreign investors rules as row with China continues