For years, Russia relied on migrants from Central Asia to fill gaps in its workforce. As demographics and the war in Ukraine drive the sharpest labor crisis in decades, recruiters are casting a wider net across some of the world’s most populous countries.

Russia estimates the economy needs 11 million more laborers by the end of the decade.

The issue was high on the agenda during President Vladimir Putin’s December visit to New Delhi, when officials signed an agreement aimed at simplifying procedures for temporary labor migration.

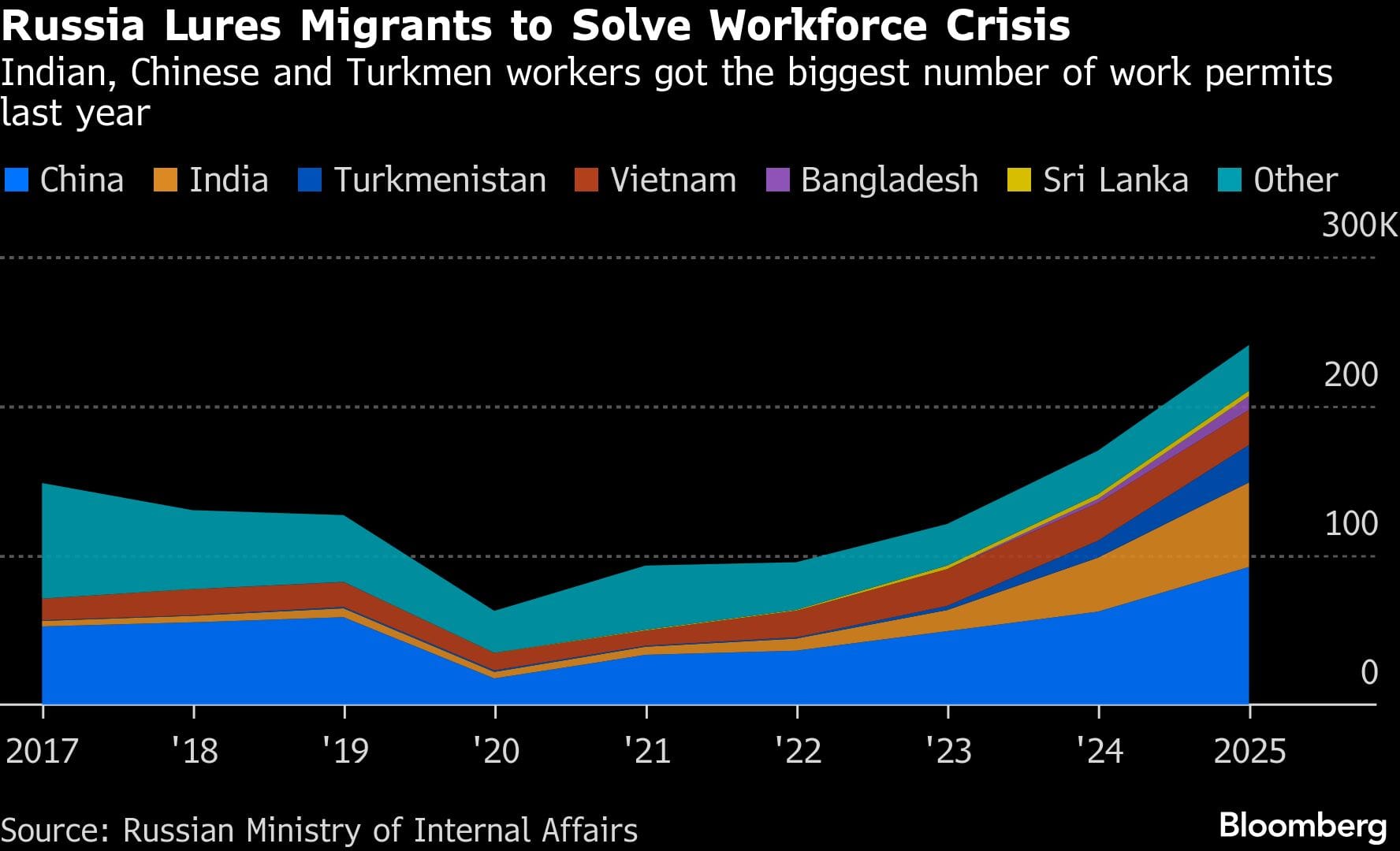

Even before the deal, the number of employment permits Russia issued for Indians jumped to more than 56,000 last year from roughly 5,000 in 2021. The total number of work permits given to foreigners rose to more than 240,000 in 2025, the highest since at least 2017, statistics from the Ministry of Internal Affairs show. While authorizations have jumped for the former Soviet republic of Turkmenistan, much of the growth in foreign labor comes from further abroad — including India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and China.

This year, workers from India and other South Asian countries have begun filling municipal jobs like clearing snow in major Russian cities, but foreign laborers are also winding up at construction sites, restaurants and other city services.

“We’re seeing a real tectonic shift in the Russian labor market,” Elena Velyaeva, operations director at the Moscow-based recruitment agency Intrud, said in an interview in New Delhi in December. The agency was set up just two years ago to bring foreign workers into the country, and Velyaeva is also looking for potential recruits in Sri Lanka and Myanmar while wanting to expand the search further.

While the US under Donald Trump and some European countries are restricting immigration, Russia’s been grappling with a demographic crisis — about a quarter of the population is retirement age — since the 1990s collapse in the birth rate. With unemployment at about 2%, one of the lowest levels globally, the economy needs new workers from abroad or it risks hitting real limits on its already sluggish growth.

Faced with the shortage, Russian companies are now more interested in attracting workers tied to their jobs by visas and contracts, Velyaeva said. Migrants from visa-free regions like Central Asia are far more likely to change employers frequently.

Intrud has partnered with the Russian Association of Welders to establish a training center for welders in Chennai, southern India, where candidates are trained and assessed before being hired in Russia, Velyaeva said.

Other agencies have organized crash courses in Russian for future hotel workers and other positions where knowledge of the language is required. For some jobs, such as in the construction industry, workers usually communicate with managers who speak both their native language and Russian, according to a recruiter with a Dubai office, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they’re not authorized to speak to the media.

“Russia is the newest addition to the list of nations employing Indians,” said Amit Saxena, director of the Mumbai-based Ambe International. “It has manpower shortage right now. So it’s a natural match.”

Ambe International only started recruiting Indian workers for Russia about three months ago, and only for the Moscow region. Now it’s also involved in recruitment for employees in Russia’s Far East — in Vladivostok and on Sakhalin island.

Putin’s war on Ukraine has worsened the already severe labor shortage. Beyond those recruited into the actual fighting, the war economy has siphoned workers from civilian sectors into military industries, while an estimated 500,000 to 800,000 working-age Russians left the country in opposition to the war, to avoid mobilization or for other reasons.

Russia also tightened regulations around visa-free migration in the wake of a 2024 attack on concert-goers at Crocus City Hall in a Moscow suburb. At the beginning of the year, the number of foreign nationals in Russia had fallen to 5.7 million, down about 10% from a year ago, although many of them are children, the Russian newspaper Vedomosti reported.

Businesses are feeling the pain.

MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC, Russia’s largest mining company, which is known to offer some of the country’s highest wages, was short about 10,000 employees in Siberia a year ago, the equivalent of about 10% of its entire workforce. The miner still lacks several thousand workers in the area, according to a person familiar with the situation.

“The shortage of skilled personnel remains one of the main challenges for Russian industry as a whole,” the company’s spokesman said by email.

JSC Shipbuilding Corporation Ak Bars, which builds both civilian and military vessels, is short 1,500-2,000 people, one reason it’s working at about half capacity, Chief Executive Officer Renat Mistakhov said.

Hiring from Asia is often cheaper for employers as well. A skilled Indian electrician may earn 25% less than what Russian recruiters offer for similar positions, job announcements on Russian and Gulf platforms indicate.

Russia is also looking to leverage deepening ties with North Korea to help plug the gap. Arrivals from the country into Russia have been on the rise since 2022, after declining under a 2017 United Nations ban on employing the country’s citizens abroad.

Many come on student visas — about 9,000 of them in 2024, the latest year for which data is available, according to the Foreign Ministry. The number of North Korean workers on Russian construction sites alone was expected to total about 50,000 by the end of 2025, the developer group Eskadra estimated, according to RIA Novosti.

The role of Chinese labor is altogether different. Most Chinese citizens receiving work visas are employed at their own production facilities or companies, said Alexei Maslov, director of the Institute of Asian and African Studies at Lomonosov Moscow State University. They are mainly active in small and mid-sized businesses such as restaurants, logistics and wholesale trade, he said.

For Russia, there’s little sign the situation will change soon.

“Russia’s population will continue to age, and the share of young people and children will keep declining overall,” independent demographer Igor Efremov said. “This is not a temporary crisis for the labor market but a long-term norm that will persist for decades and to which the economy will have to adapt.”

–With assistance from Greg Sullivan.

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also read: Despite what Trump says, Russian oil imports to India can’t be wished away after US trade deal