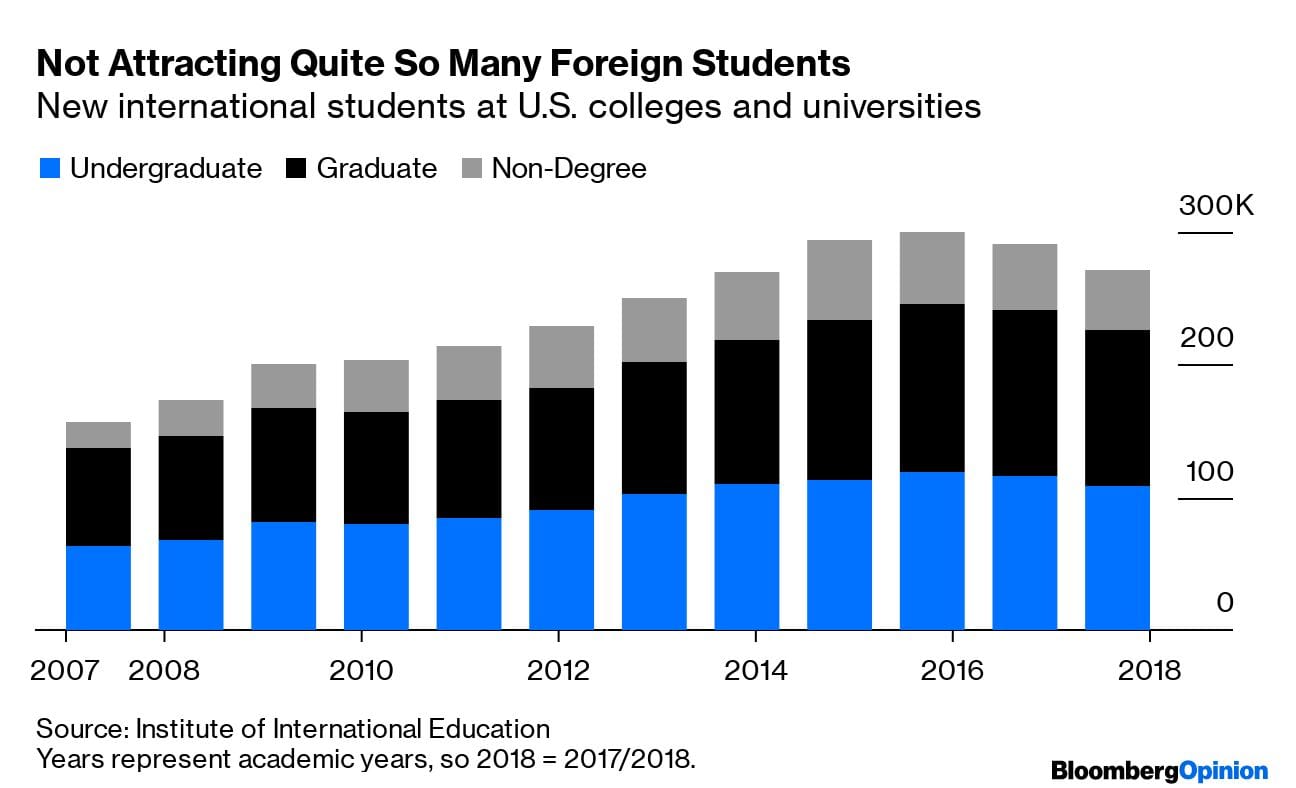

The number of new international students coming to the U.S. for college and university fell in the 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 academic years, according to the Institute of International Education (2018/2019 numbers will be out in November). These marked the first drops in the number of new foreign students since the security crackdown in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

President Donald Trump took office in early 2017, he says lots of nasty things about foreigners and his administration has begun to implement policies that make it harder to get and keep student visas. Some have thus understandably blamed him for the international student decline (including me, at least with regard to business schools). But I thought it might be useful to put the drop in foreign student enrollment in more context.

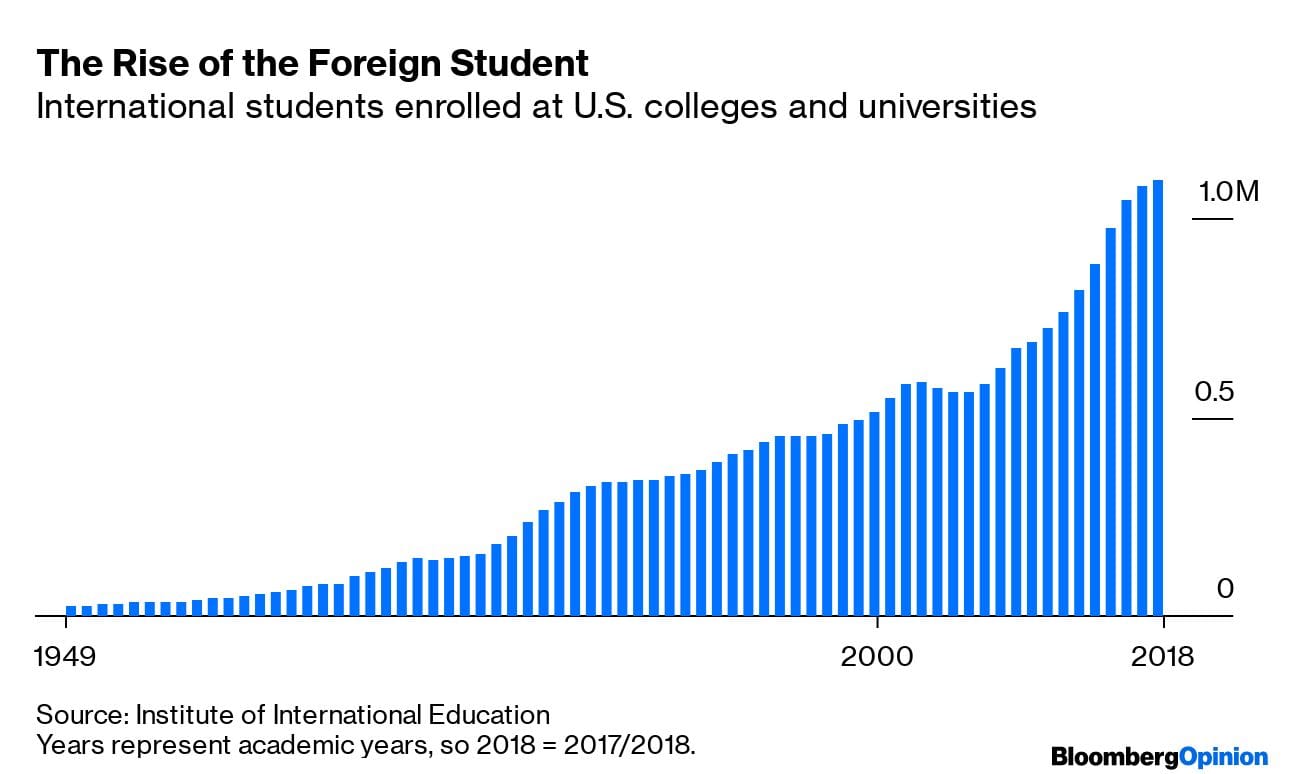

The short version: The decade from 2006 through 2015 was one of spectacular growth in international student enrollment in the U.S. The dollar was cheap relative to other major currencies, U.S. universities were hungry for cash from full-tuition foreign students, especially as states slashed funding for public universities during and after the Great Recession, and a burgeoning upper middle class in China in particular was happy to pay the price. There are several non-Trump reasons why this couldn’t continue indefinitely.

The number of international students in the U.S. continued to rise in 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 even as the number of new students declined, because the departing cohorts were still smaller than the arriving ones. Another year or two of new-student declines, and the overall number of foreign students will start falling. But it will have to fall an awfully long way before we get anywhere near the numbers of even five years ago.

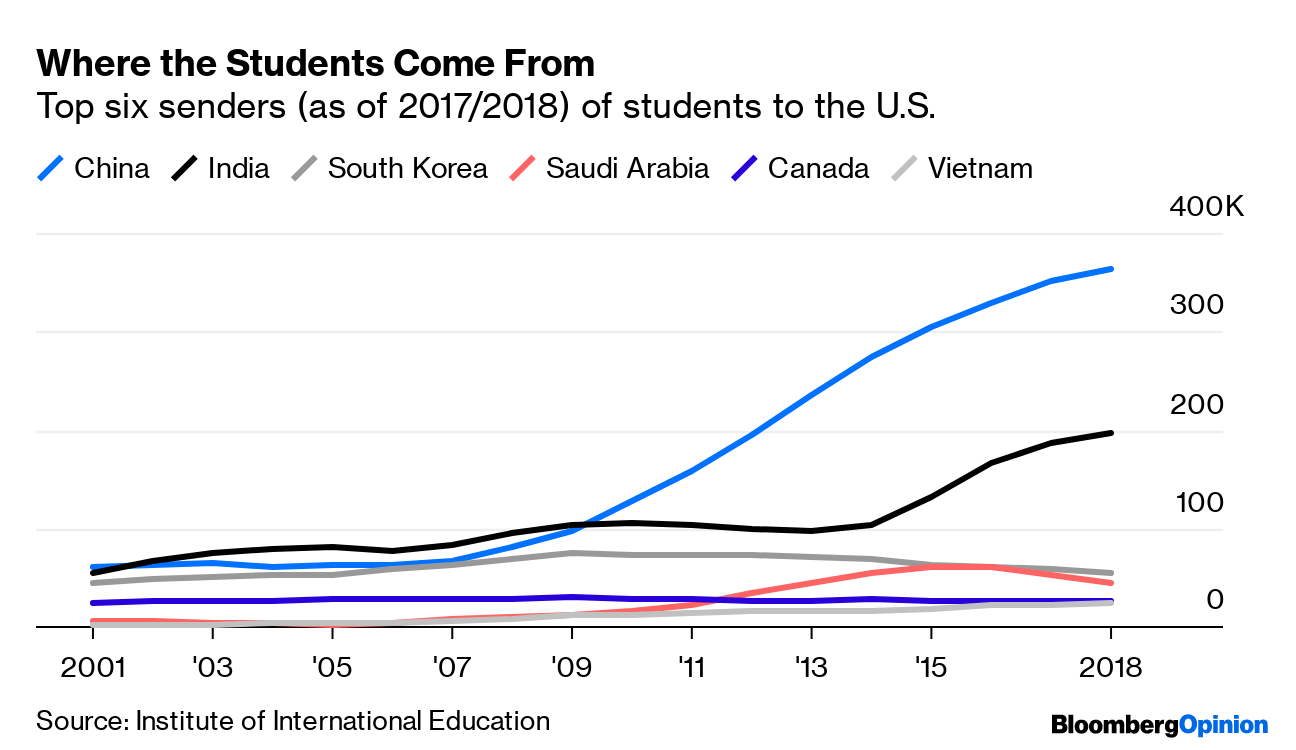

One third of current international students are from China, where rising affluence has enabled more and more young people to attend college and graduate school both at home or abroad. Similar forces, plus a young, growing population, have propelled India to No. 2, at 18%. Also driving up international enrollment in the early 2010s was the King Abdullah Scholarship Program, which President George W. Bush and the late Saudi monarch cooked up in 2005 as a way to ease tensions in the wake of September 11. The Saudis, beset by huge budget shortfalls caused by falling oil prices, cut the program back sharply in 2016, and you can see the impact in the chart below.

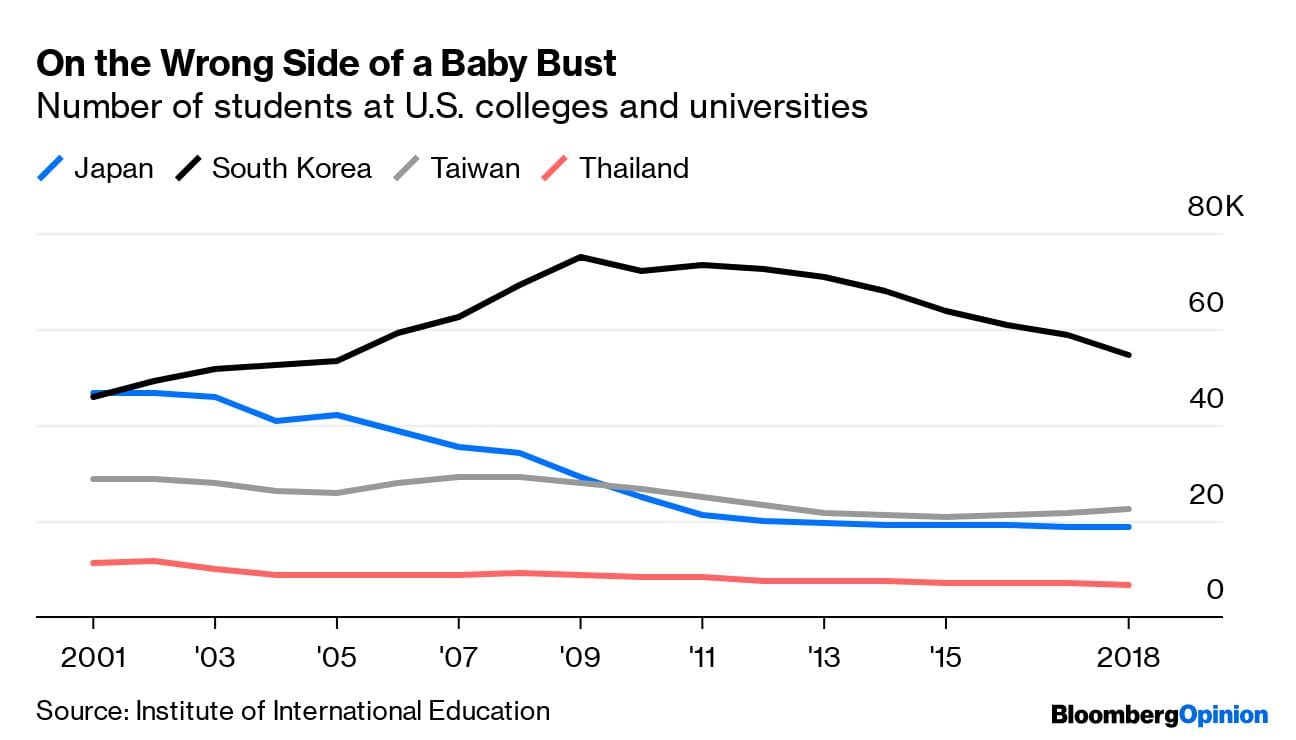

You may also notice a decline in the number of South Korean students, which seems to be mainly about demographics, as the country’s college-age cohort has been shrinking for decades and is now outright plummeting. South Korea is not the only slow-growing (or shrinking, in the case of Japan) Asian country sending fewer students to the U.S. than it once did.

Also read: Tata Trusts accused of favouring Harvard over ‘under-privileged’ Indian universities

China now also has fewer young people than it used to, and even India’s population pyramid is beginning to narrow a little at the base (that is, there are fewer four-and-under kids than there are 10-to-14-year-olds or 15-to-19-year-olds). These countries won’t be sending growing numbers of students abroad forever. Africa is the one part of the world that still has far more young people than middle-aged and old ones, but it isn’t affluent enough to send huge numbers to Western universities (yet). Only Nigeria was among the top 25 senders of international students to the U.S. in 2017/2018, at No. 13, just ahead of the U.K.

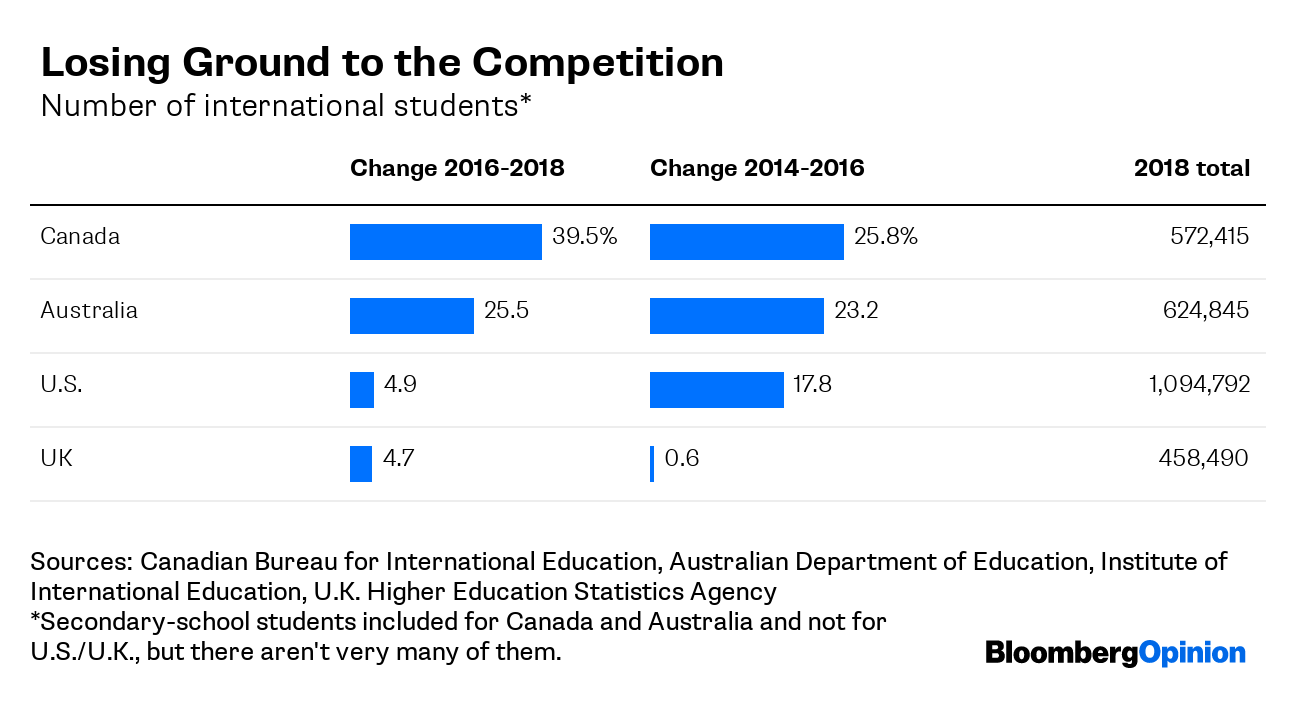

These demographic factors are beyond the power of even Donald Trump to affect. Still, if you look at how the U.S. has fared lately versus its three chief English-language rivals, we aren’t doing great:

The Institute of International Education, source of the U.S international-student statistics, is a New York non-profit that was founded in the wake of World War I, persuaded the U.S. government to start issuing student visas in the 1920s and continues to work with the State Department to encourage international student exchange. When it surveyed officials at 540 U.S. colleges and universities last fall, 83% reported that visa denials, delays and other hassles were discouraging international students from coming — up from 34% in fall 2016. Sixty percent said the social and political environment in the U.S. was driving students away, up from 15% in 2016, and 59% said they were losing students to other countries, up from 19% in 2016. Those are of course the opinions of people who work at universities, where President Trump tends to be extremely unpopular. But given that they seem to be backed up by shifts in student flows since 2016, they’re probably reflective of reality. In other words, yes, Trump is discouraging foreign students from coming to the U.S.

So far, though, the impact on the number of foreign students studying here has been modest. Also, given how fast international-student enrollment numbers grew in the 2010s, a pause might not be the worst thing in the world. Integrating huge numbers of Chinese students, some of them not really prepared for English-language instruction, was proving to be a struggle for institutions. The sharp declines in state higher education funding that made many schools so desperate to recruit international students have been replaced in recent years by modest increases, which is encouraging.

Still, an accelerating downward trend in the number of foreign students coming to the U.S. would be really bad. For one thing, these students represent a major source of income for U.S. universities and the economy as a whole — the estimated $45 billion they spent here last year is counted as a services export, and reduced the country’s current-account deficit by about 8%. For another, past international students have been a major source of talent for the U.S. when they stick around after graduation, and of good will and economic connection when they go back home.

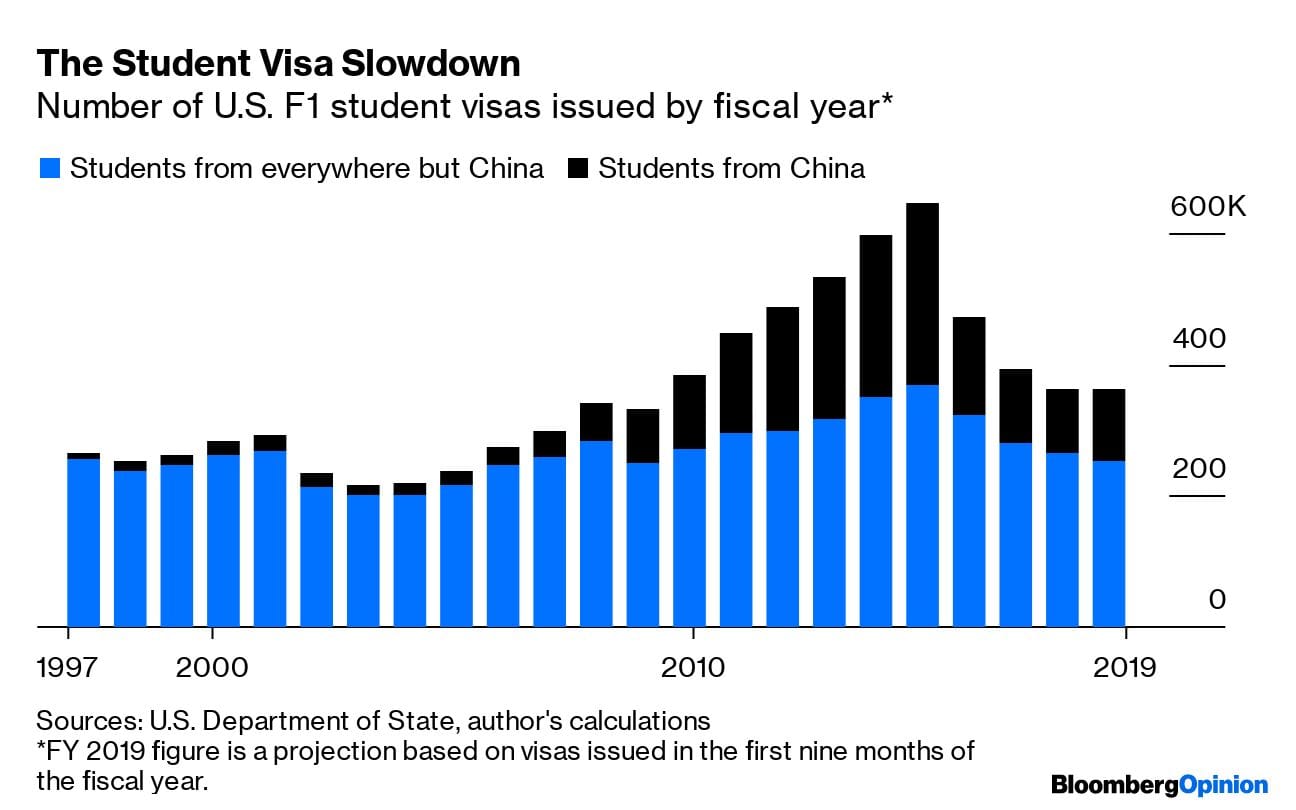

So … is the decline accelerating? One way to measure this is through State Department visa-issuance statistics, which offer a more timely and forward-looking view than the IIE data. They also have some quirks, as I learned last week when I tweeted out a State Department table showing a 43% drop in student visa issuance from 2015 to 2018. A reader pointed out that much of this was due to a the late-2014 Obama administration decision to start granting Chinese students five-year visas instead of requiring them to renew every year. To complicate things more, the Trump administration last summer again required Chinese graduate students in certain sensitive research fields to renew their visas every year, and the visa numbers for China have risen since then. Here’s the visa data with the China numbers kept separate.

Even with the Chinese students set aside, that’s still a big drop — 29% since 2015. Close to half of it, though, came in fiscal 2016, which ended more than a month before President Trump was elected. The sharp rise in the value of the U.S. dollar in 2015, which made tuition more expensive for foreigners, was probably a major factor. Saudi scholarship cutbacks played a big role in 2017’s also-large drop. The fiscal 2018 decline was smaller, and this year’s is looking even more modest, although it is admittedly a little iffy to make projections based on the numbers from October through June when July was last year’s biggest month for student visa issuance.

The U.S. and its universities are still very attractive to foreign students. Two-and-a-half years of Trump appear to have diminished that attractiveness, but they haven’t radically diminished it. Eight years might be another matter.

Also read: Why universities need to equip students with humanities education for fourth industrial revolution