Jakarta: By the time the floodwaters swallowed the ground floor of Muda Sedia hospital in Karang Baru, the building had become an island in a torrent of brown water and the power was failing. When the electricity finally cut out, a baby on oxygen support upstairs died.

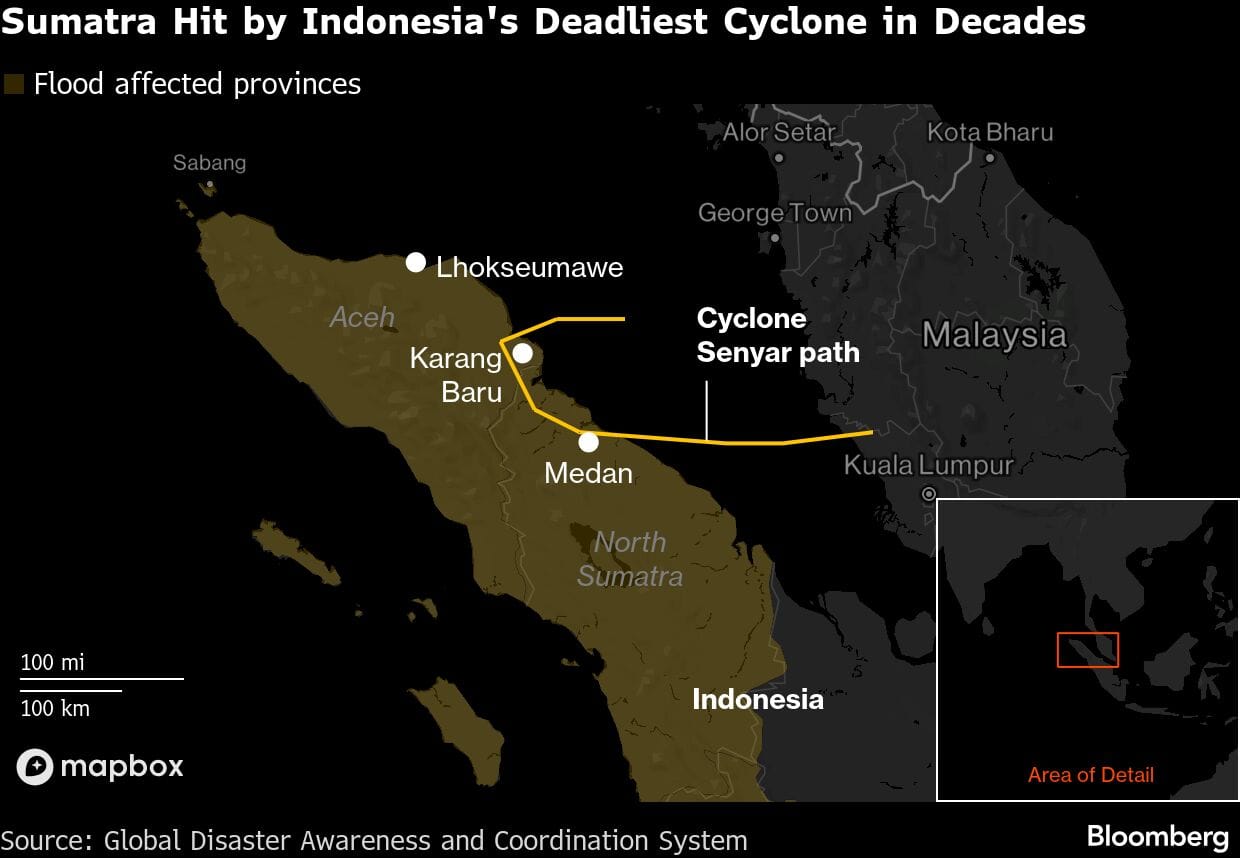

As a rare cyclone-driven storm tore across northern Sumatra late last month, hospital director Andika Putra had moved patients to the second floor in this town at the edge of Indonesia’s northernmost province. Fast-moving currents isolated the compound, trapping patients, staff and neighbors for days. Nine others perished.

“This scale of flooding has never happened before in the hospital’s history,” he said, standing outside the building in a light rain. Behind him, the waters had left broken medical equipment and a thick layer of mud spread across the waiting room floor.

More than a million people were displaced by some of the worst flooding in Indonesia’s modern history. Over 1,000 are dead. Houses, more than a hundred bridges and in some cases, entire communities, were washed away in landslides across an area half the size of California. Come nightfall, much of northern Sumatra remains in darkness, with scores of villages still cut off.

The cyclone was the deadliest in Indonesia since one that hit Flores in 1973, said Abdul Muhari, a spokesman for the country’s disaster management agency.This stretch of the island’s northern coast is emblematic of a disaster whose economic and environmental footprint now spans three provinces on the world’s fifth-most populous island. Cars sit abandoned along roads. Trash lines the streets. People with damaged fingernails queue at gas stations holding jerry cans. Roadside eateries are destroyed. Everywhere are the darkened faces of people who haven’t had access to clean water for weeks.

But through the cloying mud that permeates the landscape are thick rafts of timber — emerging evidence of how decades of industrial land clearing may have turned an unusual storm into a catastrophe.

The disaster has become a test of Indonesia’s climate resilience and development model, exposing how logging has reshaped floodplains that are home to tens of millions of people. Sumatra is a major hub for palm oil, mining, timber and oil and gas, industries that generate tens of billions of dollars in exports a year and depend on now damaged roads, bridges and ports.

Weak planning ahead of Cyclone Senyar, which also wreaked havoc in Malaysia and Thailand, played a role in the destruction, as did the ferocity of the storm, which dumped as much as four meters of rain in some areas in a single day.

Yet across this stretch of small towns, one feature of the deluge stands out in survivor accounts: the extraordinary volume of timber racing through the flood zone.

Harrison, a 39-year-old resident of Langsa, woke on the second night of the storm to find himself floating on his mattress on the first floor of his home, already one of the highest in the neighborhood. He and his neighbors crammed into his attic, sharing rice and instant noodles, filtering brown water for baby formula and trying to sleep on the roof. They held on to whatever they could, “because falling meant being swept away.”

And from that tenuous perch, they sat and watched rivers of logs surge past. Several kilometers away, logs would dam up around a large mosque, creating an impenetrable nest of timber larger than a football field.

“All we could see were large trees — logs carried by the current — and rooftops,” Harrison said. “The city was gone.”

Approaching the district of Aceh Tamiang by road, the destruction stretches for miles. Green cornfields have turned brown and emergency tents dot the highway. Residents dry mattresses and furniture in front of damaged or collapsed houses, while cars and trucks sit half-buried in mud. Villagers rush toward passing vehicles asking hopefully, “Are you bringing aid?”

Old Wounds

Indonesia, a country of 280 million people that sits on the Pacific “Ring of Fire” seismic zone, has seen its share of outsized disasters, from the epic eruption of Krakatoa in the late 1800s to the Indian Ocean tsunami on Boxing Day 2004, which killed around 230,000 people, some 170,000 of them in Aceh province on Sumatra’s northern tip.

But while monsoon floods and landslides are common, none in recent memory have produced the havoc unleashed by Cyclone Senyar. “People are most afraid of December because of the tsunami trauma,” 26-year-old Bintang Agam said. His parents died 21 years ago, victims of the Aceh tsunami. “For Acehnese people, even a three-meter wave is enough to bring back old wounds.”

Officials and environmental watchdogs say the devastation was amplified by land clearing. Sumatra, home to some of Southeast Asia’s largest remaining tropical rainforests, has experienced massive vegetation removal over the past two decades as logging concessions, mining licenses and palm oil plantations proliferated.

Indonesia had the fourth most primary tree cover loss globally from 2023 to 2024 after Brazil, Bolivia and Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to an analysis from the World Resources Institute.

“There is a known link between tree cover and flooding,” said Sarah Carter, research associate at WRI’s Global Forest Watch. “Trees absorb water, acting like a sponge to prevent floods and landslides. Their roots help to prevent landslides by holding the soil together.”

Dewi Ratna Sari, a nature-based solutions manager at WRI in Indonesia, said the floods show how urgently officials need to factor landslide risks into development planning. “People need to understand why we should protect this flood plain area,” she said. “We need to adapt because this is already at a crisis stage.”

Came From the Mountains

Inno, 60, was among dozens of people taking shelter under the bridge that connects Medan, a provincial capital, and Aceh Tamiang regency after his neighborhood of about 400 homes was swept away. Many houses were destroyed after being hit by logs.

“They came from the mountains; everything is being cut down,” he said. “We don’t know who is responsible, but everyone knows it’s happening.” “Nothing is left,” he added, while eating a cup of instant noodles. “I’ve lived here for almost 50 years, and I have never seen a flood this devastating.”

Indonesian officials last week began questioning multiple companies over their land practices in Sumatra, saying early findings from aerial surveys may provide evidence that paves the way for criminal proceedings.

Officials have temporarily suspended operations in the area of PT Agincourt Resources, which runs the Martabe gold mine, along with state-owned plantation company PT Perkebunan Nusantara III, North Sumatra Hydro Energy, and a unit of palm oil producer PT Sago Nauli. The country’s environmental ministry said it has also sealed several mining sites in western Sumatra, without elaborating.

United Tractors, the parent company of Agincourt Resources, said in an exchange filing that its unit has temporarily suspended operations to focus on relief efforts. The other three firms didn’t reply to requests for comment.

Indonesia has said recovery efforts will cost more than $3 billion, a bill that will stretch government finances as the nation’s economy contends with lackluster growth, market volatility and weak consumer confidence under President Prabowo Subianto’s still early tenure.

The Long Wait

Two weeks after the rain, the scale of annihilation is still becoming evident.

North of Aceh Tamiang, in the coastal city of Lhokseumawe, a onetime boomtown that drew the likes of Mobil Oil to its Arun gas field, aid workers are trying to reinforce government relief efforts, as far as access allows. An airport partly run by state oil company PT Pertamina has reopened, allowing flights to ferry gas canisters and other goods to the interior.

Outside of town, thousands of hectares of rice fields that were weeks away from harvest are now buried under mud. Further inland, electricity is out and roads are treacherous. Household items such as dining tables, refrigerators and electric fans are scattered along the way. And north, along the coastal highway, a bridge over the Krueng Tingkeum River sits torn in half, cutting off the main access to Banda Aceh. It was broken, residents said, when a torrent of logs slammed into it.

One military doctor stationed near a shelter in an inland village of Bener Meriah regency, one of the hardest hit after a landslide destroyed the main road, said for survivors, their main problem now is hunger because aid has been too slow to arrive. Army medics were instructed to redeploy immediately to Aceh Tamiang and Pidie Jaya.

Prabowo, returning directly from trips to Pakistan and Russia, visited an evacuation shelter in Aceh Tamiang on Friday, apologizing in front of dozens of children gathered there. “God willing, we will fix this. The government will step in and help everyone,” he said. He urged local authorities to strengthen environmental protections. “We must protect our environment and our nature. We cannot cut down trees carelessly.”

As the President finished speaking, people in the crowd implored him for more help. “Send heavy equipment,” one yelled. “Our houses are flooded, please help us,” another cried out.

“What is unique about this disaster is the vast size of the affected areas,” said Ade Soekadis, the executive director of Mercy Corps Indonesia. “A million internally displaced people are spread over thousands of villages across three provinces, and the government doesn’t have the resources to build emergency shelters” everywhere they’re needed, he said.

Harrison, the Langsa resident, said no support of any kind arrived for 10 days. He also saw no police or other officials in his neighborhood during that time. With looting rife, money became useless.

At night, no one went outside, but at dawn, desperate people made their way through the mud and floodwaters, searching for anything to survive. It wasn’t uncommon to find bodies inside vehicles and the smell of decay filled the air. “Everyone wandered aimlessly, confused, because they were all searching for food and water,” he said.

Even in Medan, one of Indonesia’s largest cities, the scale of the floods was unlike anything residents could recall. Three rivers burst their banks, inundating neighborhoods that had never flooded and sending water into the official residences of the governor, regional military commander and police chief. Parts of the toll road linking the city to its international airport collapsed.

“It feels as if nature is angry with us as human beings,” said Budi Ramadhan, 45, whose house on the outskirts of the city was engulfed in two meters of water. “The floodwater is black and foul-smelling. This is something unnatural.”

(Reporting by Chandra Asmara. With assistance from Aaron Clark, Yasufumi Saito and Eko Listiyorini.)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also Read: In rare bloom in Sumatran jungle, Rafflesia Hasseltii—the weird, stinky flower that made a man cry