There is a natural human tendency to assume that your generation has it harder than everyone else. Even by those standards, however, baby boomers (and some older millennials) are on the receiving end of an extraordinary amount of resentment. You could fill a good-sized library with all the books devoted to boomer-hate.

Much of the blame heaped on the older generation is for ruining the world with their neoliberal economics, refusal to vacate the houses they bought long ago on the cheap, destruction of the climate, accumulation of all the wealth, and so on. A lot of this antipathy is unfounded, and none of these accusations is completely fair. Boomers faced higher mortgage rates, and maybe had to live in smaller houses in more rural areas than they would have liked. Much of the climate damage predates the boomer generation. And neoliberalism worked: Young people today have more wealth than their parents did at their age.

All this intergenerational resentment is not so much unjustified as misdirected. The younger generations have ample reason to be upset with the boomers — for getting bigger retirement benefits and leaving behind lots of debt, which threatens future prosperity.

But for some reason these issues do not elicit the same anger. There is no widely popular youth movement to cut spending or entitlements the way there are ones to freeze rent, build more housing, eliminate student debt or offer free child-care.

In fact, President Donald Trump is hailed in some quarters for his political savvy in abandoning entitlement reform. The president has even expanded retirement benefits, as many Democrats have called for; the budget law he signed last year cuts taxes on Social Security payments and gives seniors an extra deduction, both of which make the debt worse. And yet there were hardly any objections, from either party.

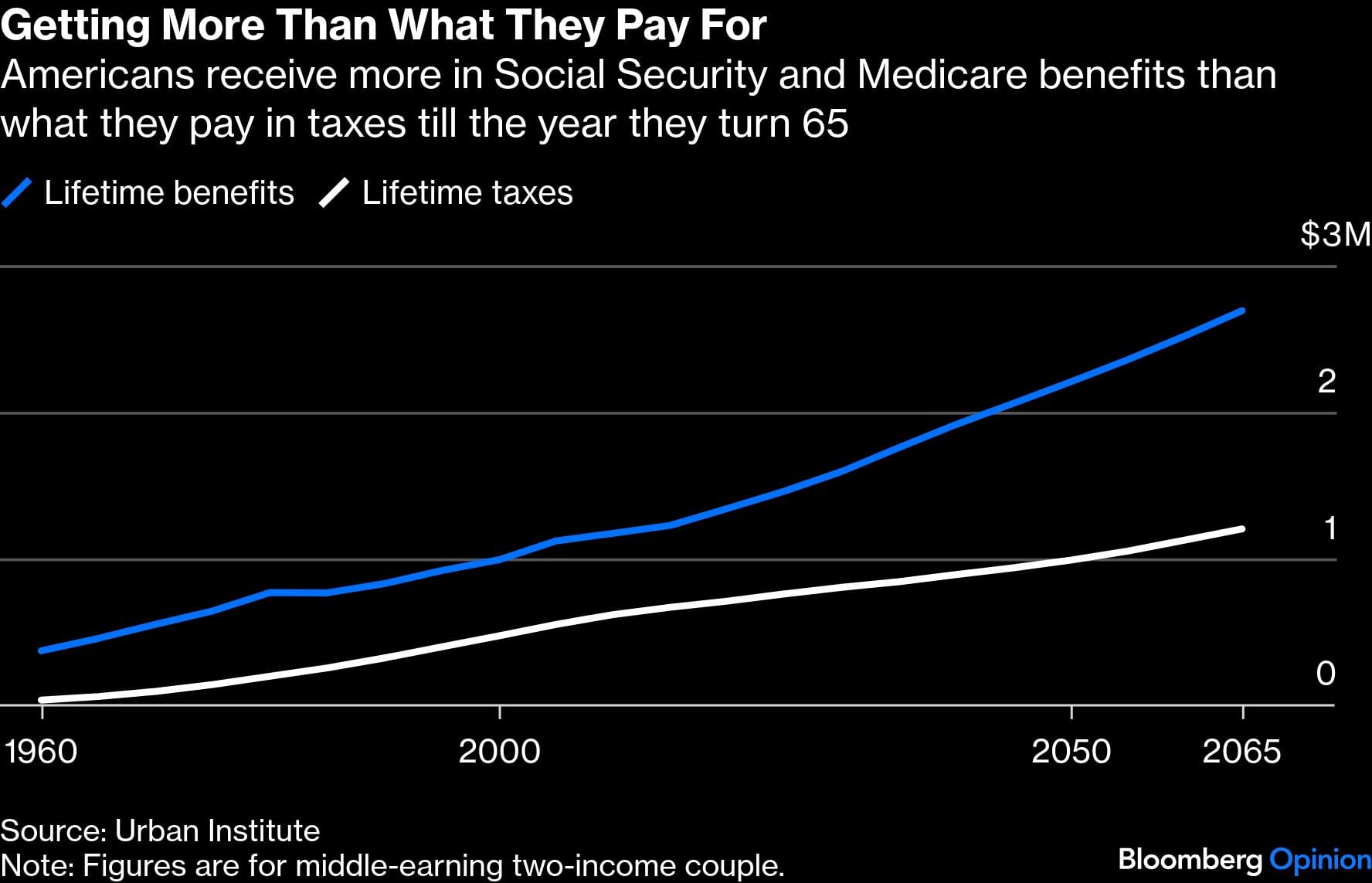

It is remarkable: As benefits to seniors are increased at its expense, a generation that feels it deserves more is mostly silent. Part of the explanation is that this isn’t new; the value of old-age entitlements has increased over time relative to the taxes they pay for them.

It is not just in the US. In France and the UK, the income of seniors is also growing at a faster pace than it does for workers. In France, pensioners actually have higher incomes than working-age adults. Yet younger French citizens, who have many economic challenges and their own resentments, don’t march in the streets in support of the government when it tries to cut retirement benefits.

Another possible explanation is that young people don’t resent old-age benefits because they realize that they too (if they’re fortunate) will be old one day. It’s notable that the payroll taxes that fund entitlements in the US are featured prominently on every pay stub. That makes it seem like a benefit they’re paying for, and deserve, even if each generation gets more than it puts in.

There is also a cultural taboo against cutting benefits for the elderly, who are seen as more vulnerable. For years they had the highest poverty rates, though now they have the lowest. Even when there is a debt crisis, pensions are rarely cut.

Finally, there could be an ideological reason that young people are so reluctant to support entitlement cuts for the old. Young people today, especially among the more activist set, tend to skew left. Resentment of a boomer for owning a house they’d like to live in — a house he paid little for — is in a sense resentment of capitalism itself. Supporting cuts in Social Security, on the other hand, or even a reduction in increases, is to favor shrinking the welfare state.

The idea seems to be that the market economy produces a finite amount of resources that are unfairly allocated, while the welfare state can be expanded as needed. In fact, the opposite is true. The government’s spending ability is far more limited than the market’s production capacity. The US can’t keep expanding benefits for each generation, especially as the population ages and interest rates increase. Much as the younger generations might want to, ignoring this problem will not make it go away.

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of “An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.”

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also read: Trump says ICE makes ‘mistakes’, Good’s killing a ‘tragedy’ as backlash over tactics grows