New Delhi: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

By the time this piece is published, the quote above will be all over social media. It is, after all, one of the most quoted parts from Toni Morrison’s compelling Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1993.

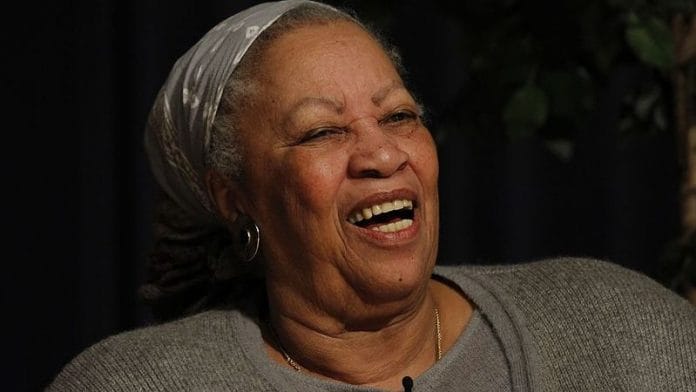

It is also a quote that will comfort many Morrison fans in the wake of the legendary African-American author’s death Tuesday at the age of 88, as they re-read her extraordinary novels — The Bluest Eye, Sula, Tar Baby, Jazz, Song of Solomon, Paradise and her most beloved book of all, Beloved.

In all of them, she prioritised the experience of black people, especially black women and the sacrifices they made.

“I’ve spent my entire writing life trying to make sure that the white gaze was not the dominant one in any of my books,” said Morrison, who became the first black woman to break into the canon of the Great American Novel, which was dominated by white men such as Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

In the days to come, much will be written about her life and times, her legacy and her multiple awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Pulitzer, the Commander of the Arts and Letters from France, a few honorary doctorates from Harvard, Oxford and more, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the many Most Important American Books lists that Beloved was on and, of course, her Nobel for literature in 1993.

But Morrison wasn’t one to confine herself to one role. As an editor with Random House, where she was the first black woman in a senior role, Morrison brought in a number of black writers to the fore, including Angela Davis and Gayl Jones, and edited legendary boxer Muhammad Ali’s autobiography.

In 1970, her own debut novel, The Bluest Eye, was published. From then right up until 2019, when she appeared in a documentary about herself, titled Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, in between teaching, writing librettos for operas, children’s stories, plays, non-fiction and essays (such as the one she wrote for The New Yorker after the election of Donald Trump), she was a voice that would not be silenced.

And in many ways, her greatest legacy, her lasting relevance, is in the way she used her voice, the way she understood the power of storytelling and language, the need to use that power wisely.

Her Nobel Prize acceptance speech in Stockholm is a poetic case study in that same power.

Also read: Remembering Kamala Das, feminist Indian writer who chose a ‘stern husband’ in Islam

Language as power

“Once upon a time”, she began her speech, cleverly using that standard childhood fable opening line to tell a story about an old blind woman who is asked by a bunch of children whether the bird they hold is dead or alive, in a bid to prove her a fraud.

“The old woman’s silence is so long, the young people have trouble holding their laughter,” said Morrison. “Finally she speaks and her voice is soft but stern. ‘I don’t know’, she says”. “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.”

“Her answer can be taken to mean: If it’s dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it. Whether it is to stay alive, it’s your decision. Whatever the case, it’s your responsibility… I choose to read the bird as language and the woman as a practiced writer. She’s worried about how the language she dreams in, given to her at birth, is handled, put into service, even withheld from her for certain nefarious purposes. Being a writer she thinks of language partly as a system, partly as a living thing over which one has control, but mostly as agency — as an act with consequences.”

Morrison went on to decry the use of language to perpetuate crimes of racism and sexism, by despots and fascists, and by mindless media.

“Ruthless in its policing duties, it has no desire or purpose other than maintaining the free range of its own narcotic narcissism, its own exclusivity and dominance. However moribund, it is not without effect for it actively thwarts the intellect, stalls conscience, suppresses human potential. Unreceptive to interrogation, it cannot form or tolerate new ideas, shape other thoughts, tell another story, fill baffling silences…”

“Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek — it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind.”

“Sexist language, racist language, theistic language — all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.”

Morrison then turned the story cleverly on its head, giving the children their voice. And through their questions — about language, about questions, about narratives and those experiences that remain nameless — the old woman and the children understand and trust each other.

“Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation,” the children said. “Tell us what it is to be a woman, so that we may know what it is to be a man; what moves at the margin; what it is to have no home in this place; to be set adrift from the one you knew; what it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.”

“Finally”, she [the woman] says, “I trust you now. I trust you with the bird that is not in your hands, because you have truly caught it. How lovely it is, this thing we have done — together.”

This, then is the way forward. In a world that is ever-more polarised and unwilling to listen to each other’s language, Morrison’s masterful story about the power of language becomes ever more essential.

“We got more yesterday than anybody. We need some kind of tomorrow,” says a character in Beloved. It is, after all, in our hands.

Also read: Girish Karnad’s last work was an unfinished autobiography in English