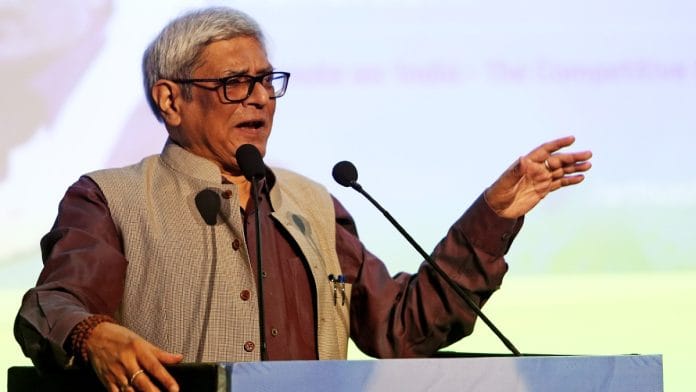

Noted author and economist Bibek Debroy, who had been chairman of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council since 2017, passed away Friday. He was 69.

Also a member of the NITI Aayog, Debroy had to his credit the authoritative translations of the Bhagavad Gita, the Vedas, Puranas and Upanishads from Sanskrit into English.

In 2016, ThePrint Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta interviewed Debroy on NDTV’s Walk The Talk, discussing the challenges of governance and how Debroy played a key role in initiating a systematic cleanup of redundant central government laws.

Here is a transcript of an excerpt from the interview, edited for clarity.

Also Read: ‘BJP never believed in reform’—what ex-PM Manmohan Singh said in 2004

Shekhar Gupta: Hello and welcome to Walk the Talk. I’m Shekhar Gupta, standing in front of the national Parliament, which is in session, and where we are complaining all the time that bills are not being passed. But we are so busy complaining about bills that are not being passed, that we are completely missing out the story of the bills, in fact laws, which are being repealed. So this may not be a champion Parliament in passing new laws, but it’s been quite a champion in repealing old laws. And my guest today, Bibek Debroy is somebody who has instigated this change, who keeps instigating it from behind the scenes. Bibek, welcome to Walk the Talk. We have to talk about your work on Mahabharata, we have to talk about your work on the economy, but right now, because this is something going on, and only what is not being done in Parliament gets attention and not what’s being done. So give us an idea of what’s being done and why.

Bibek Debroy: At the moment, your question is focused on the Union government. In our country, laws don’t always mean Union government, they can be state governments also. But your question, the first question was about the Union government. When one is talking about old laws, old laws are sometimes statutes, where the entire statute can be repealed at one go.

SG: The entire law.

BD: The entire law goes at one go. There are also statutes where you need to remove a section, repeal a section.

SG: Or to modernise the law.

BD: Or to modernise the law, to rationalise it, harmonise it. Now the second one is a much more complicated exercise.

SG: Tabhi toh (that’s why) you’ve gone around with a sword and cut at whatever can be cut from the wood.

BD: That’s correct. So about 1,200 odd statutes by way of four different bills.

SG: 1,200 laws.

BD: Now, in the Union government, what is important is two points. Firstly, 50 per cent of the total statute base is gone.

SG: India has about 2,500 central laws; about half are gone.

BD: Just gone. Second thing I want to say is that these are things that should have been done in 1947 or 1950. When the Constitution was being framed. But what was done was a very perfunctory exercise in 1960-61. A little bit more systematic in 2000-2001. This is the first systematic cleanup.

SG: I think Mr Vajpayee talked about it for the first time.

BD: Yes, and in 2000-2001, some bit was done, about 250 went.

SG: I think that was Jaitley.

BD: Yes, Jaitley. This is the first time a cleanup has been done on such a large scale.

SG: So give us some examples of laws which have now disappeared. And why we will not miss them.

BD: You see, a lot of these, let me be factually correct, a lot of these are appropriation acts. Which just continues just like that, so for no particular reason.

SG: Many ordinances carrying on since 1948. I read your paper on this.

BD: Yes, that’s right. Old is not gold. I have something called the Bengal Districts Act, which goes back to 1836.

SG: And what does it say?

BD: All it says, it empowers the Bengal Presidency and now the West Bengal government to create as many districts as it wants.

SG: Any state can do it anyway.

BD: That’s right. So why do you need a statute for this?

SG: Yeah, because maybe tomorrow when they did something, somebody will go to court and say, this was not done according to this law.

BD: Fine. But what happens when you do something like this, is you go back.

SG: It becomes a nuisance.

BD: No, you check. Right? You check whether there are any cases, let’s say in the last 50 years, under any of these. And in all of these instances, there’ll be no cases. But yes, you’re right. Why is it important to scrap them? Because they’re used for harassment.

SG: You know, because there’s a case I remember from my life as a reporter very vividly. This is when electronic voting machines were first introduced on an experimental basis. I think 1985 or ‘86 under Rajiv Gandhi’s government. And Rajiv had won this massive mandate. So five by-elections were held with voting machines. Congress lost all five. And suddenly the government went to court saying these elections should be set aside because the Representation of the People Act describes the ballot as a paper. So a government that brought in technology because it lost elections and it was set aside. And then the law was amended. So you saw the power of a badly-worded law, which has not kept pace with the time.

BD: You see, I react to that by saying that when one is talking about legal reform, there are many components of that.

SG: And for me, that was a big disappointment with Rajiv—somebody who promised technology—just because he lost elections.

BD: There are several components. One is getting rid of the old statutes, old sections in statutes. People say this is not important. It is not important against the entire canvas. In the entire canvas, you also have rationalisation issues. You have harmonisation issues. You have reduced state intervention. You are modernising the laws. And the speed of the dispute resolution system. No one is saying that those are being ignored. This is just one component of that jigsaw.

SG: So you talked about this Bengal Act. Tell us about some other laws which have now been completely repealed and nobody will miss them.

BD: Well, from the same year, same vintage, let me give you the example of the Bengal Bonded Warehouse Association.

SG: 1836?

BD: Yes, that law said when it was going to be wound up, the assets had to be given to the East India Company. Why do we need that? But the more important point is, such laws exist in other countries also. In London, all taxi cabs are governed by Hackney Carriage Act, or Tonga law, which means every taxi cab in London has to carry enough hay for the horses. The difference is that, here, those laws are used to harass people.

SG: There, nobody will stop the guy to say ghaas kidhar hai (where is the hay).

BD: No one is. People are unlikely to do that. In fact, they laugh at it.

SG: But in fact, we’ve seen some of those things happen in India because some cop discovers some law.

BD: That’s correct. I can give you the example of the Aircraft Act which was passed in 1934. And therefore, given the context of that decade, it defines aircraft to include not only the aeroplanes, but also kites and balloons. So technically, before flying a balloon, you need permission. So if the cops descend on you and ask you, where is your licence for flying kites? Where is the licence for flying balloons? They’re strictly within their powers.

SG: But I think we’ve seen this happen recently in Bombay. Because in Marine Drive and sort of these beach areas or coastal areas, picnickers tend to light these lamps that go up in the air.

BD: Yeah.

SG: And they’ve been declared a security threat. And I think action has been taken under the same law.

BD: That’s right. There are, of course, the other elements which are much more important. As I said earlier, the entire statute doesn’t go, the old section has to go. The Transfer of Property Act. That part of it which deals with mortgages is an example. I can give you examples from many commercial and economic laws, and the often talked about Indian Penal Code. It’s not just Section 377. It talks about waging war against an Asiatic power. What on earth is an Asiatic power? Why do we need that today? So there is a cleanup which has also got to do with old sections in a statute.

SG: How was an Asiatic power defined?

BD: You see, Macaulay is blamed for all kinds of things. But I think we fail to acknowledge his enormous contribution in almost single-handedly drafting the Indian Penal Code.

SG: Fali Nariman says that he (Macaulay) used the English language almost perfectly there.

BD: I’m sure the Asiatic power then would have referred to Russia … there’s no definition in the statute as such. But there must have been a background which I’m not aware of.

SG: Right. Maybe a friendly government or a friendly state. But even our normal submission law, it includes not physically attacking but saying adverse things about a friendly state. How do we define a friendly state? Those are finer changes we need.

BD: Those are finer changes which have to be statute by statute, section by section … and in my point of view, these are things where cops harass the small vendors.

SG: Absolutely.

BD: So all these statutes, they are anti-poor.

SG: Bibek, tell us something. We all watch Parliament live proceedings. How come we’ve never noticed that 1,200 laws, half of all of India’s laws, have been repealed? I mean, law examinations will change, teaching of law in India’s colleges will change, law book houses will have their shelves emptied out.

BD: Eventually. Because this, as I said, is the easy part where you’re repealing it in its entirety.

SG: Bare acts will disappear now.

BD: Yes.

SG: So how does it happen in parliamentary practice so quietly?

BD: Well, I am somewhat upset that journalists don’t write about it. There were actually four bills.

SG: There were two bills in May 2015. That’s the reason I caught hold of it.

BD: There were two bills in May 2015. And there were two bills passed by the Lok Sabha. They were pending in Rajya Sabha. They were passed by Rajya Sabha about two weeks ago. So that’s how we have this.

SG: Each legislation has what? Does it repeal many laws?

BD: No. Each bill, you see here, you are repealing the entire act. So by and large what it does is a single repealing bill. These are the statutes I am mentioning at one stroke. So a whole bunch of them.

SG: A whole bunch of them at one go.

BD: It’s much more difficult when you have to change a section. Then you have to go statute by statute. That is the next step.

SG: So are most laws that needed to be repealed still fully at the central level been repealed?

BD: Fully, fully. Yes. You see there are some which were central laws but they were on state subjects. So there are about 240 of those. Those have been referred to the states. Otherwise where you could repeal all of it at one stroke, that’s over now.

SG: Will you give us an example of those that have been referred to the states which in your view should be repealed?

BD: Let me put it like this. Broadly, if you look at the constitutional nature, most of the laws, most of the things that economists and you also, despite not being an economist, would call a factor market are things like land and labour. Land in its broad sense. Land is not just ownership of land. So several of these are land-related. A few are sort of what might be called labour-related. So mostly those. These are, strictly speaking, what should happen is, the Union government should not legislate in areas that are on the state list. And even if there are areas that are on the concurrent list. Unless enabling laws are needed. But governments have not always followed this. So we have a bunch of laws which technically are state government subjects. And to state the obvious, India has over a period of time become too centralised unnecessarily.

SG: In fact, and sometimes it’s happening in crisis. For example, the NIA. Creation of NIA happened in the aftermath of 2008 Mumbai attacks. I don’t think normally states would have allowed such a thing. And one thing just in passing because it cropped up.

BD: People talk about the Seventh schedule. But they do not realise that the Seventh schedule today is not the Seventh schedule we got in 1950.

SG: It’s been amended many times.

BD: And over a period of time, items have moved from the state list to the concurrent list and items have moved from the concurrent list to the Union list.

SG: So what is the action in states? You are now saying states have started it. Frankly, I latched on to you after I saw a story from Rajasthan. That you either repealed 200 odd laws or they are in the process of being repealed. You are advising the Rajasthan government.

BD: Well, Rajasthan is quite a story. And the background to that is the only time a state attempted to do something like this was Kerala, towards the end of the 1990s. But that was a very limited exercise. Now one of the problems with starting this exercise in a state is that at the Union government level, you have a set of all the statutes in one place, you have the inventory, the database. You start with the state government, you don’t even know what the complete set is. So in Rajasthan, there were almost 50 statutes which we knew existed.

SG: But you couldn’t find them?

BD: But no one had copies of those. They had not been used in court cases. The legislative assembly did not have copies. Finally the copies were obtained from the government printing press.

SG: I thought maybe the US Library of Congress or something.

BD: I doubt it. So in Rajasthan, there was a total database of about 1,250. I’m going to be guarded and careful. I don’t want to confuse the issue. But there is always a problem with the numbers, that are you counting the amending acts separately? Are you counting the appropriation acts? I am just being pedantically correct. Having said that, there were 1,250. Out of those altogether, about 250 have gone in that first brush. First slicing away. A single, two repealed bills. Which are the ones that can be just eliminated at one stroke. We have now moved on to the next step.

SG: So that means one-fifth of all laws have more or less gone?

BD: One-fifth, yes, roughly 15-16 per cent.

SG: Do you remember any remarkable ones out of these?

BD: These were the easy ones. But any interesting ones out of these? Like your locust law and your balloon law. No, often I don’t remember. Because the more interesting ones will come in the next exercise.

SG: Such as which?

BD: Which is when we are going to rationalise. We are going to harmonise. In higher education, do I need 65 different statutes? In the state. I have 65 different statutes for higher education alone.

SG: That’s why our high courts are now clogged with writ petitions.

BD: Yes, and every time you have a statute, it causes confusion because you don’t really have a bunching together of cases.

DG: Somebody comes and appeals to the Supreme Court, then you refer to this.

BD: So in Rajasthan, we moved on to the next step. Which is the rationalisation, harmonisation, all of that. And the big one there, typically in any state, the bulk of the statutes are land related.

SG: Land or labour?

BD: Not labour, because labour, take Rajasthan for example, you’d be surprised to know that there is only one statute in Rajasthan on labour. That’s the Shops and Commercial Establishment Act. Because states implement Union labour laws. They don’t have their own laws. The states where we are beginning this exercise, we have not started. It’s early stages, we are discussing it. And I must give credit to the chief minister. Something like this happens only when the chief minister actually gets interested. And in Rajasthan, this has happened because the chief minister was interested. The two states where we are proposing to take this exercise now forward are J&K and Maharashtra. These are two that we want to start.

SG: Both are willing?

BD: Early stages, both are willing.

SG: So, Bibek, how did you get interested in this? I know you do many things, from Sanskrit to Economics.

BD: Actually what happened was rather interesting. In 1993, Dr Manmohan Singh was the finance minister. And there was an individual, a famous economist whom I shall not name, who was going to Paris to attend a conference funded by the UGC. And the per diem at that time was $65 a day. So because he was an economist, he knew Dr Manmohan Singh, so he sent a letter. Those were days of letters and faxes. He sent a letter to Dr Manmohan Singh. Will you please relax this and make it not $65, $90. It goes to a Joint Secretary, who says, wait a minute, why should we arbitrarily increase it from $65 to $90 for Shekhar Gupta? We should increase it for everyone. Someone else says, do we need that section at all? Goes higher up, someone says, wait a minute, do we need FERA at all? Goes all the way up to Dr Manmohan Singh. He says, why only FERA? Let’s set up a body to look at all the legislation to see how it should be changed.

SG: That’s how it happened.

BD: That’s how I got roped into this process.

SG: Why don’t you tell us the name of the economist?

BD: The name of the economist? Well, had he been alive, I would have mentioned. Professor Ashok Rudra. That’s how this project started. This is how the project started.

SG: This should be called a $65 a day revolution.

BD: So this is how the project started, which had the rather unhappy acronym of LARGE—Legal Adjustments and Reforms for Globalising the Economy. I headed that project from 1993 to 1998.

SG: That’s how you discovered these laws. So in fact, this was, if I may say so, one of the giant steps in evolution of reformist intellect.

BD: You see, the trouble is most of the time, reforms are driven by economists. Economists do not understand the importance of the law. And lawyers and economists typically don’t talk to each other.

SG: Journalists understand neither.

BD: No. Journalists understand both, probably. Some journalists. But just for record’s sake, actually I wrote a book in 2000 or 2001 called In the Dock: Absurdities of Indian Law, which documented all of these old laws. Thankfully, many of them have now gone.

SG: So what next? Are we looking at our next stage in Parliament of these amendments now? Once the jhadoo work (cleanup) is over?

BD: Now it becomes a question of examining statutes item by item, which is a much more difficult and time-consuming exercise. And someone has to drive it. Because there have been several reports on identifying old laws. The reason it got momentum was because the PMO set up a committee under Mr Ramanujam. And the PM was personally interested in it.

SG: Which PM was it?

BD: This PM. Because he’s been talking about it in his campaign speeches.

SG: In fact, I heard his speeches. But I said 1,200 laws were repealed. How come nobody took notice of it? And then I saw the story from Jaipur.

BD: Well, I wrote a piece in The Indian Express. But you’ll be sorry to know that, maybe after you left, no one reads The Indian Express.

SG: No. I read every word that you write anywhere. But the fact is, I did not quite figure out the mechanics of this.

BD: Okay.

SG: I’m not saying I was not trusting you. I’m not trusting the Prime Minister. But I said, ye maloom nahi pada kaise hua (we don’t know how it was born). I didn’t realise that you put all of them on one bill. And you can vacuum clean them.

BD: Yeah, there were four law commission reports towards the end of 2015. Then the Ramanujam committee. All of it came together.

SG: So the basic wisdom you draw is, challenges of governance don’t change with history. Basic challenges remain.

BD: Yes, because depending on how you define governance, and let’s not get into that, a large chunk of the Mahabharata, which we normally don’t read, is about what today we would call governance. This happens when Bhishma is lying down on his bed of arrows, and instructing Yudhishthira. This occurs in the Shanti Parva, in the Anushasan Parva, on the duties of kings. And most people don’t realise that this is richer than Kautilya’s Arthashastra. And let me give you two examples. One from the civil side, one from the criminal side. On the civil side, Bhishma tells Yudhishthira, that these are the most important 17 kinds of civil cases, and you must address them in order of priority. And number one in that list of 17…

SG: Order of precedence?

BD: Order of precedence. And number one in that list, in that day and age, was breach of contract.

SG: Which is still a problem. In fact, in ease of doing business, we ranked 183 in a group of 185 on contracts.

BD: On the criminal side, there is a statement, that if someone is relatively rich, you must not imprison that person, because the costs have to be borne by the public exchequer. Instead, a monetary penalty should be imposed on that individual.

SG: I’m sure Mr Subrata Roy would really appreciate this.

BD: Someone who is relatively poor, someone who is relatively poor shouldn’t be imprisoned. If I state this in isolation, without telling you that this is in the Mahabharata, most people will deduce that this is an argument from a paper written by one of the University of Chicago Law and Economics guys. No, it’s in the Mahabharata.

SG: Right. So, I think on that note, I’ll let you go back to Mahabharata, and let you go back to your mind, which I know is not divided in silos, but I think multitasks all the time, Bibek, wonderful to chat with you. You are such a brilliant guy.

BD: Thank you.

Also Read: Top grain producer but also top in undernourished kids: When MS Swaminathan talked India ‘paradox’

Rest in peace, Mr Debroy. I cherish your article on fountain pen ink and many more.